by David J. Lobina

For someone who sees himself as a person of the Left, at least in the sense in which the political right and left were conceptualised by Norberto Bobbio ages ago – that is to say, as moral and political stances towards equality (and inequality) – and more concretely, as a sort-of anarchist, at least in the sense, this time, of being suspicious of authority, top-down impositions and ideas, and much preferring a society composed of spheres of self-realisation instead from the bottom up,[i] the advent and prominence of so-called ‘identity politics’ in recent years, especially in the English-speaking world, and most clearly, in the US, has been surprising, bewildering, and rather frustrating.

Even though identity politics is usually associated with the Left, both by friends and foes, I agree with some thinkers from the Left I actually follow, such as the academic Brian Leiter, that this kind of politics may well be ‘the narcissism of the aspiring bourgeoisie, who want to get their share of the “capitalist pie”, including their share of “respect” as reflected in language and culture’ – and likewise for the concept of equity so common and so often defended these days, which is not really a liberal principle per se, but more of a neoliberal keyword: no universal social programs to be set up, but instead we shall have micro-interventions here and there that can only produce a more ethnically diverse elite. Under these conditions, inequality and capitalism remain untouched, class politics unmentioned, the result a Left without the economics or the socialism, and on we go with elite representation and such worries (seriously, whatever happened to class politics?).

Rather surprisingly, at least to me, the obsession with such diversity concerns is ubiquitous here in the UK too, including at my daughter’s primary school in London, one of the most diverse cities in Europe. In June each year there is a so-called Diversity Week, which according to the Head Teacher is about ‘taking pride in who you are and all of the things that make you ‘you’, especially your differences’ (you can strike out the word especially from that statement), the main point to be conveyed being that ‘one opinion, lifestyle, religion, family make up, or cultural heritage is not more important than another; we are all individuals and our differences are what make us stronger as a community’.[ii]

As a case in point, the school once entered a local flower cart competition, and the chosen message on the cart was: We are all different, and that’s fine.

All of course laudable, at least at first sight. My point in this column is to push back a little bit, and to do so from the point of view of universality and commonality, which I regard as a much more significant property of human thought and belief systems – indeed, of human nature tour court. Or as the La Fontaine Academy flower cart could also have advertised at the competition: We are all the same, and that’s fine too!

Now, I have often talked about linguistic and cultural diversity here at 3QD Tower (for instance, here and here), and sometimes I have a bit at pains to point out that the myriad diverse forms we observe in language and cultural customs around the world are really the result of underlying capacities for language and culture (Language and Culture, say) which are invariant and universal in our species – mental systems composed of primitive concepts and suites of combinatorial principles that generate the various outputs we observe in language, the arts, music, etc.

And as I have also argued in some of other posts (here and here), different languages do not form different worldviews, different cultures are not inscrutable to outsiders, different musical styles are enjoyable by everyone (cue this famous 10,000-strong Japanese rendition of Beethoven’s 9th symphony), and any person from any part of the world would be able to acquire whatever language and cultural customs they are exposed to in the first 4 or so years of life. There is a kind of universal fabric in our species that explains these by-now common points in cognitive science, a commonality that unites us all.

This applies to identity politics too, based as such a politics is on beliefs about people’s characteristics (and characters), a much more subjective domain than basic properties of cognition such as the capacity for language and culture – in the jargon of cognitive science, the features and properties of language and culture qua systems of our minds are not penetrable to one’s beliefs and thoughts in the way that ideas about one’s race, sexuality or gender (but not biological sex) certainly are.

Or as the philosopher Jürgen Habermas has apparently put it, but a quote I wouldn’t send to the Head Teacher of my daughter’s school – maybe to the Executive Head Teacher (here, in the original in German; the screenshot is from a reputable Twitter account of an academic, here):

The lure of individual differences is strong at all levels, though, and I have experienced this often as a university lecturer, especially when it comes to the psychology of intelligence or reasoning – some people are faster than others in problem-solution tasks and puzzles, after all, and students often want to know how and why. I first noticed this fixation when I started my PhD in 2007, so a while before identity politics was on anyone’s radar. I would often sit in my supervisor’s lectures, and sooner rather than later there would be a number of questions about individual differences in processing this or that stimulus – cognitive psychology is all about computational processing, memory load, attention, etc.

My former supervisor would usually tackle these questions by talking about our common anatomy, but I never thought this tactic landed very well at the time, though I took the main point to be reasonable enough – it went something like this: a biological organism follows a kind of blueprint given the environmental condition the organism has evolved under, and everything else being equal, we are born and grow to have two arms and two legs, two eyes, one brain, etc., and the same goes for our cognitive capacities.

That is, everything else being equal, our visual system develops in such a way as to generate the same kind of 3-D representations of the external world, thus allowing us to navigate the world in the same sort of way; our linguistic systems acquire roughly the same language of our communities (and, now, with universal schooling, of our countries) and we thus are capable of communicating to each other in this language, even though we are all exposed to different amounts and kinds of linguistic input in our first years of life; our attention and memory capacities also develop in similar ways, and thus cognitive load limits are roughly the same for everyone (in this case, there are outliers at both tails of a standard normal distribution, which is also the case for much of the data in the psychology of reasoning and decision-making, but the generalisation remains true and nothing is exceptionless in cognitive psychology anyway); e così via.

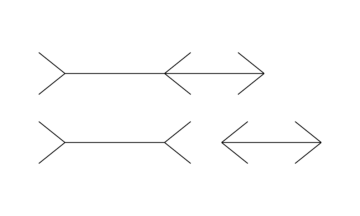

In addition – and again, under the condition that everything else remains equal, which is to say that there are no lesions, diseases, or abnormal environmental conditions – there are plenty of what may be called psychological laws, applicable to most peoples, with some variation here and there. In the case of perception, most people are susceptible to classic visual illusions such as the Müller-Lyle illusion:

Most people are also susceptible to processing generalisations such as the Stroop Effect, the result of task in which participants have to name the colour a word is written (or printed) in, and where it is usually observed (almost universally, actually; I used to run this experiment at educational and science fairs, to great success) that naming the colour of a given word is easier and faster if the word matches the colour the word it is written/printed in. Try for yourself here! Or just attempt it by comparing your performance to the two groups of words below:

There are some universal generalisations in language processing too, especially in the case of reading, with so-called garden-path sentences such as

The horse raced past the barn fell

What happened upon reaching the word fell? Something did not compute, as your language comprehension system had completed a full sentence by the time it reached the word barn and the new verb right after it did not quite fit the constructed interpretation at that point. But the sentence is perfectly fine, it’s just a reduced version of the sentence the horse that was raced past the barn fell, and it is perfectly grammatical (there are myriad such examples, especially in relation to syntactic ambiguities of various kinds).

In the aforementioned posts here at 3QD, moreover, I have argued that it is generally possible to translate the thoughts and meanings of one language into another, not on a one-to-one basis (not word for word, that is, or even phrase for phrase), but in terms of the content or message being conveyed (often with a paraphrase), and it is certainly possible for anyone to relate, understand, and indeed appreciate the emotions or feelings expressed in art forms (be these in music, painting, or what have you) other than the ones you have been brought on in a particular region or country of the world.

So far, so cognitive, but I think the point also applies to the human belief system, at least as it pertains to human rights and freedoms, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a good point to start here, especially in relation to some of its most fundamental principles. The right to dignity, liberty, and equality cannot but be regarded as universal values – that is, as values that any person would consider an intrinsic part of their own person – and the same goes for the right to life and security, and thus the prohibition of slavery, the right to freedom of thought, opinion, and expression, and many others.[iii]

My point here, to be clear, is that these values belong to human beings qua human beings, and regardless of any individual differences – indeed, it is despite of any individual differences that such rights and freedoms belong to everyone, and precisely because of the commonality and universality involved in being, well, human.

It is a platitude to say that all human beings have the same kind of anatomy; it should also be a platitude to say that we all have the same set of mental states (emotions, beliefs, desires, etc.) available to us, despite apparent linguistic and cultural differences, but this point is not as appreciated as it should, with the opposite belief – namely, that certain mental states are only possible in certain languages or cultures, the loss of any of these languages and cultures a loss to humanity – a sentiment more often assumed than based on any actual evidence; and it should definitely also be a platitude to say that we all share some core human values, but this is not quite the case within the context of identity politics, where values are constantly relativised in terms of identities and cultures, and where people are often judged and evaluated in terms of their supposed identities and credentials.

To come back to my daughter’s primary school, where children are aged 5-11. I doubt that there is any need for a diversity week in a school in London – a multicultural city where learning about other languages and cultures happens naturally – and in fact I think it may well be counterproductive to have exercises such as these, in London or elsewhere, where supposed differences are explicitly pointed out and (over)emphasised, especially without the counter of what makes us all the same, the universality of human nature. And as a sort-of anarchist, I am naturally sceptical of such crude, top-down exercises to begin with.

But the whole thing is probably moot at this age, anyway; observe such children during play time (and playing is what these children do for the most part) and the issue of ‘one opinion, lifestyle, religion, family make up, or cultural heritage…being more important than another’, to paraphrase our Head Teacher, is often just inapplicable. Or said otherwise, children do not assume, as adults may do, that some opinions, religions, and families are more important than others; instead, they typically treat these phenomena each in its own terms, with no adult filter. If anything, children should be encouraged to discover the world, and not be told what the right thoughts or beliefs are, which they might not be receptive to anyway.[iv]

Indeed, I very much doubt that exercises such as diversity weeks are as formative for primary school children as some teachers seem to presume (and it is an assumption). Some teachers do appear to think that they are changing the world one child at a time, but what children this age are mostly doing is developing their cognitive capacities as well as some of their most basic social skills, and the support they require is the right kind of scaffolding for cognitive and social development to take place. It is unlikely that anything of ethical or moral standing is being solidified, settled, or even properly absorbed at this age – to believe otherwise would be an unfortunate lapse into ideology or just a demonstration of not insignificant naivety. There really is no guessing what belief systems children will form in their teens and beyond, or what sort of people they will be in their adult lives.

In any case, I would also point out that identities as commonly described – to wit, as race, gender identity, and sexual orientation, but not being a certain sex, age, or married (these are all ‘protected characteristics’ from discrimination from the UK Equality Act, the legislation our school uses to frame the talk around differences) – can be significantly mutable, any category within each identity has rather fuzzy borders, and in the end they capture the character of a person in necessarily superficial ways. There’s much more to a person that the pre-established ideas of what one is supposed to be like according to identity politics.[v]

Now, back to the use and abuse of the term ‘fascism’ next month!

[i] Rudolf Rocker, an anarchist thinker I have written about in this column before, is a good exemplar of what anarchism in general entails; a longer paper of mine about his thought is forthcoming in the journal Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, and a preprint is available here.

[ii] There were some other surprises in store for me, as a parent of a single child, and as someone who grew up in South Europe. One such surprise is the parlous state of the public sector in the UK and the lack of public-service ethos generally on display. This is of course the result of decades decimating the public sector by governments of all stripes, including introducing some features from the private sector into the world of state schools. There is no civil-service test to become a school teacher in the UK, for instance, as is the case in countries like Italy, France or Spain. All you need is the requisite qualification (this would be but the first step of the process in Italy and Spain) and then you can apply for open positions, initially as a newly-qualified teacher (the salaries are set by the government, but this does not make school teachers civil servants, but merely public sector workers). As such, there is a higher churn rate in state schools than I had experienced before – in Italy or Spain, a job at a state school is usually for life – as well as situations where one can be promoted into senior positions rather quickly, as is the case at my daughter’s school – the Head Teacher there is slightly younger than me, is on the young side to be a Head Teacher in the UK, statistically speaking, and moreover has not been in education for very long (he has at least 6 fewer years of experience than myself in education). Another surprise is the parent politics at UK schools, perhaps also the result of making this sector more business-like, with various parents’ organisations and governor structures in place, resulting in rather close (and sometimes closed!) relationships between senior staff at schools and the self-appointed ‘cream’ of the parent body (what was it that Beckett said about the cream of Ulster?).

[iii] The Declaration makes little mention of social rights and this is by-the-by here, though it is worth bringing it up – a result of class politics the Declaration most certainly was not.

[iv] But, anyway, what is this nonsense about no opinions, lifestyles, or cultural heritages being more important to others? I certainly don’t rate the general opinion of a conservative politician regarding inequality, or the lifestyle of a gigolo, or the cultural heritage of child marriage. I want the right kind of indoctrination at my school, thank you very much.

[v] As a case in point, the linguist John McWhorter speaks rather eloquently about the limitations of race as an identity marker in this interview with the biologist Richard Dawkins, starting at 36.40.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.