by Thomas Fernandes

Interest often begins in surprise. It may arise from the encounter of something new or the clarity of insight, when a complex thing finds a simple resolution. We may also be blind in two ways. The first lies in what we fail to notice, and thus cannot be surprised by. The other lies in what we take for granted, missing the complexity.

Consider something you’ve likely seen all your life and are possibly afraid of: the honeybee. Honeybees represent but a few species of the 20 000 species of bees, most of which are solitary bees laying their eggs in tunnels or dead wood. Yet they are the most notorious. But how well do we see them?

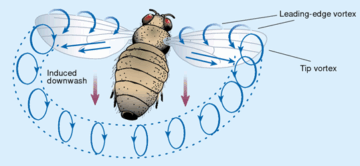

We notice them flying, but are we surprised? Until the 2000s, scientists could not explain how bees fly. As the story goes, in the 1930s, engineers considered bee flight aerodynamically impossible. It was found that, by all accounts, their wings shouldn’t be able to lift their bodies. Yet the answer was found in a very different mechanism of controlled turbulence. Specifically, it was found that bees rely on leading edge vortices. Insects in general do not rely on steady flow of air but create controlled turbulence called a vortex at the top of their wings. By sweeping their wings at a sharp angle bees generate “horizontal mini-tornadoes” that are then pinned on top of the wing. The low-pressure zones of the “eyes” of those mini tornadoes carries them aloft. This is very similar to staying aloft in water by sculling: moving your hand back and forth at an angle in a figure-eight movement. In this pattern both directions create lift, contrary to bird flight. Slow-motion footage reveals bees “swimming through the air” more vividly.

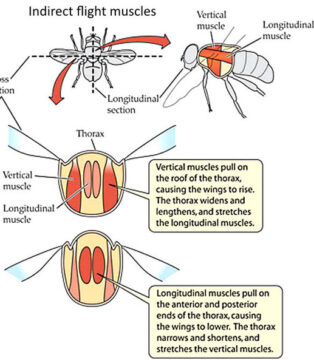

This discovery only brings about a new deeper mystery that might fail to surprise us. To keep those vortices anchored to the wings, bees must beat their wings fast, 230 beats per second on average.

This isn’t just fast; it is physiologically astonishing. In what are called synchronous muscles (our muscles), one nerve signal creates one muscle fiber contraction. The contraction rate is limited by the refractory period between stimuli, the period it takes before it can contract again. Muscles, not nerves, set the upper limit on contraction speed, not exceeding 100 Hz across animal species. Yet bees are flapping their wings 230 times per second. The solution? Asynchronous muscle. Asynchronous muscles come in antagonist pairs that can contract multiple times from one nerve impulse using intrinsic feedback at the muscle fiber level. There is a stretch activation of the muscle causing contraction immediately on response which will in turn activate the antagonist muscle producing remarkably constant wingbeats. It creates contraction cycles at the thorax-wing system resonant frequency. Think of it a bit like plucking a guitar string: it will oscillate at its determined frequency. Only in this case the muscle is actively driving movement.

Despite the elegant solutions developed 400 million years ago in insects, a central question remains: the energetic cost. Bee flight is a very energy intensive process estimated at 50 to 100 times the resting metabolic rate. By comparison, a human experiences a 20-fold increase in metabolic rate while sprinting. How can bees sustain such intensity for so long?

Their extreme endurance rests on the most ancient tool: the mitochondria. Flight muscles of bees are packed with mitochondria up to 50% of the total muscle volume; twice the proportion of a marathon runner. Those mitochondria are constantly supplied with oxygen and fuel. Bees breathe through a tracheal system, a branching network of air-filled tubes which delivers oxygen directly to muscles. At small scale such tracheal system is very effective. A steady input of fuel is secured via massive use of rapidly metabolized sugars. Sustained flight uses about 10 mg of sugar per hour for a 113mg bee. To grasp the scale of this number at human mass it would equate consuming 6 kg of sugar per hour (24 000 kcal). Such adaptation comes at a steep cost for the bees. So much activity increases cellular wear, oxidative damage that accumulates with every wingbeat and drastically reduces their lifespan.

These energy constraints don’t just explain and limit how bees fly, they shape how they think. Every foraging decision becomes a metabolic calculation. The marvels of bee flight can be seen as engineering solutions, yes. But they are not standalone marvels. Each comes with costs, risks, and rigidities. In honeybees they push toward coordination, timing, and memory.

Not only can bees discriminate between flowers based on color, scent, shape, electric charge and nectar quality but they remember which were the most profitable flowers. As they learn and memorize bees will develop routes of foraging, optimizing path to visit all the most rewarding flowers. Those routes are in constant revisions should conditions change. Those are not just spatial routes but temporal ones as well. Nectar quantity is not constant in flower. The lantana flower, for example, changes color after pollination. It signals to the bee: no nectar here. Other flowers will replenish nectar daily and peak at different times of day.

These inference processes can only be fine-tuned by effectively measuring the nectar sugar level bringing us back to physiological adaptations. Bees not only have sucrose detectors in their mouth but also their antennas and their feet. Their antennas can detect sucrose concentration as low as 2%, able to track the scent of sugar from the briefest contact without landing. Their feet will only be satisfied by high reward, responding only above 30% sugar concentration upon landing. It’s a two-stage quality control system that prevents wasted energy on poor flowers. If the flower does not pass, the bee must also update her future routes and clues interpretation to avoid future energy waste.

Collecting nectar has another overlooked complexity as each flower requires specific motor skills to access nectar. The difficult access to nectar is adaptive for the plant both in selecting for preferred pollinator but also ensuring effective pollination by forced contact with pollen. Bees are not born knowing how to operate every possible flower. They must learn, becoming more efficient at handling each flower with repeated experience. On a given foraging trip, a bee typically focuses on the flower species currently offering the richest sugar reward. This behavior, sometimes described as floral constancy, has the efficiency of batch processing: by limiting the variety of flowers visited, the bee improves retrieval speed. This also enhances pollination success for the plant ensuring pollen reach plant of the same species.

Once collected the nectar is stored in the “honey stomach”, a pouch separated from their digestive system. Despite its name, bees use it not only for transporting nectar but also for carrying water used in hive cooling. An average nectar foraging bee returns with a little above 30mg of nectar. In extreme cases, this can be obtained from one flower producing a lot of nectar. Or by hundreds of less productive flowers. Consequently, foraging trip ranges from 15 minutes to 2 hours based on distance, number of flowers and climate conditions. Overall, the observed difference in foraging behaviors can be quite large. Yet they are produced by the same biological constraints and cognitive tools, only applied to different environments.

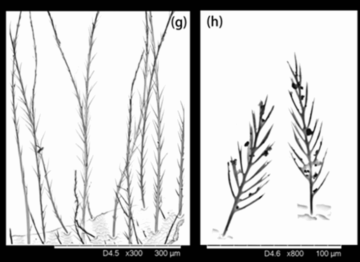

Nectar is not the only resource a bee needs to collect. As a vegetarian evolution from wasps, bees collect pollen instead of insects to provide protein for the larvae and young bees. The resulting optimization of foraging behavior seems to have favored specific foraging trips for pollen and nectar but rarely both at the same time. Physiologically every hair on a bee’s body is precisely shaped to capture pollen, branched like tiny trees to maximize surface area and pollen retention. As a bee moves through flowers, these tiny branches gather pollen. Pollen forager bees will continuously use their front legs to collect and pack pollen from their body hair into sticky balls stored in the “pollen baskets” on their hind legs. But bees don’t just brush against pollen, they attract it. Pollen grains are naturally negatively charged. Flight generates static electricity, by friction with air particles, that charges the bee’s body positively, effectively turning her into a pollen magnet.

The energy-reward balance is a key criterion behind every decision. Nevertheless, scales can be tipped. Moderate wind? Distance must be revised for proximity instead of quality. An incoming storm? collect as much as you can near you and go back to the hive. Too much humidity? Forget pollen collection for now. It will rain tomorrow? Expend more energy foraging today. Their weather forecasting ability resides mostly in their antennas. These antennae detect humidity changes, temperature drops, and airflows with such precision that bees consistently predict weather in advance, critical for creatures who can only fly in fair conditions.

This foraging activity is a feat of intricate decision-making that we are only beginning to understand, made possible by bioengineering we are still studying. And yet this is only half the story. The bee has not even returned home.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.