by TJ Price

I did not expect to be watching so-called “reality TV” this weekend. It’s not a habit of mine; I’m not the kind of person who typically consumes that kind of media—at least, not willingly. There’ve been a few exceptions to this: back in the early aughts, I did watch almost all of Jersey Shore, and at some point in the ensuing years, a friend cajoled me into watching one episode of Real Housewives of Orange County. When one of the titular Housewives began to run water from their hyper-stylish tap in order to wash a whole (raw) chicken, I yanked the EJECT lever harder than a fighter pilot in distress. In most reality TV, I find there’s a kind of mise-en-abyme effect, one whose chasm can sometimes echo with l’appel du vide. How endlessly recursive, this construct of hyperreality—especially when those on-screen seem compulsively aware of the media tesseract to which they have surrendered.

This is what led to my fascination with Love is Blind, during a recent visit to my friend Chelsea. Love is Blind, to be brief, is a reality television show predicated on stripping out the vector of physical attraction in the courses of the initial stages of dating. Contestants are limited to adjacent rooms (called “pods”) separated by a constantly-shifting panel of screen-saver pinks and reds—in some moments resembling the walls of a womb. There is no access to personal phones or computers, and when not in the “pods,” the contestants are divided into either the men’s quarters or the women’s quarters. These are only ever shown as communal spaces, with a variety of couches and chairs, and a kitchen area, seemingly used for the sole purpose of beverage preparation.

These beverages are seen constantly throughout the episodes, in uniformly brushed, metallic drinkware of different sizes and shapes. There are mugs, wine glasses, and tumblers, all of which shine dully under the klieg lights: burnished and yet tarnished simultaneously. When in the “pods,” contestants are often seen holding them while perorating blandly on the necessity of authenticity in relationships—either unaware of the irony or willfully ignoring it. (At one point, a contestant even had a total of seven of these vessels grouped around them in the shot, suggesting that quite a bit of imbibing had occurred during the “date.”) Because the composition of the drinkware is opaque, it is impossible to know what kind of beverage they are consuming, beyond the presence of blurred-out bottles of Corona and cans of High Noon on the small shelves. Though none of the contestants ever appear particularly inebriated, they do sometimes seem high on their own supply—victims of unjust bullying, or perhaps simply perpetually unmated, the slightest provocation can cause them to oscillate wildly between maudlin and ecstatic.

Beyond the gilded cups, there are other strange accoutrements: each contestant comes into these “dates” carrying fastidiously-sized notebooks and writing implements resembling a gaudier Fisher Space Pen, decorated in—you guessed it—burnished gold. In some shots, you can get a glimpse of typed up script, taped to the inside of these notebooks—surely to prompt the contestant with pre-programmed questions. I wonder about the writing gremlins off-screen, charged to come up with these heuristic queries—if their task is done with an ear toward manipulating the on-screen drama in some way. Taking Tennyson’s ancient axiom “tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all” to an illogical extreme, these contestants have various ways of referring to their voice-only interactions, but by and large the overwhelming term that comes into parlance is the word “connection.”

“I just feel like we have such a good connection,” implores one contestant after another, desultorily picking at their fingernails, or looking anywhere except for directly at the camera. “And it really hurts when one of the other girls [never “women,” despite the name of their domitory space] comes in saying you said they’re your number one.” In other convoluted sentences, when one of the girls is talking to one of the other girls about one of the Other Girls, the dialogue is something like “I know that she knows I know, you know? But does he know that she knows I know?” To this befuddling which the other girl responds with an eager vigor: “Oh, I heard that she knows you know, but who knows what he knows.”

It’s past sunset, inching toward ten o’clock, and I’ve got a headache. We’re watching this streaming on Netflix. During one of the brief interludes, I make a comment on the insipid music that’s playing to lead the viewer from one segment of the episode to the next. It’s nondescript, synthetic sound with vocals engineered to reflect the current theme—“Don’t know what’s happening / but I like it // I didn’t know love at all / til you”—moaned dispassionately by a spayed, anodyne voice. Chelsea tells me that she read somewhere that when the episode airs, there is more popular music filling these interstices, but when the show is streaming, it is replaced by this aural pablum. “I’ll give you my lungs / if you need them to breathe” a reedy, faux-Sheeran voice (aided by a distasteful amount of Auto-Tune) floats over a scene of one couple, adding another layer of inauthenticity to the already-dystopian premise.

At some point, I realize the show has shifted—some of the contestants have progressed from “connected” to “engaged.” It turns out that a contestant must propose marriage (and be accepted) in order for the (proverbial) veil to be lifted; for them to lay eyes on one another for the first time. Then these newly engaged couples are whisked away to Honduras, where they test-drive their Brand New Relationship and exclaim over how “crazy” it all is. I wonder if I should start keeping track of the times certain words are used and discard the idea. A certain passivity has stolen into my limbs, and it’s making me fidget—little autonomic spasms of my calf muscles, as if my body is sending urgent messages to my brain to get up and walk away, walk away before it’s too late—but my brain is occupied by the recursive conversations, in which nothing is ever communicated and yet in which both of the speakers are urgently describing how important “communication” is. The paradox is multiplying in front of my eyes, developing new layers. This, I think to myself, is how falling into a black hole must feel. I have passed the entertainment horizon. I am becoming spaghettified, flattened.

Onscreen, a couple luxuriates in a hot tub, intimately adjacent to one another, but staring straight ahead, neither looking at one another nor even where the other is looking. “I still find it strange to hear your voice and see you at the same time,” the guy admits. “I feel like I shift my gaze slightly, to create the atmosphere of the pods … when you talk sometimes and I don’t look at you, I feel that vibe again.”

The camera lingers on the couple. Their faces are like masks, stippled by the coruscating, underwater lights. Their eyes betray nothing.

How long have I been watching?

When did they both turn their eyes to start looking directly at me?

Time passes. I’m no longer sure how much of it, and at what tempo. I’m aware of a slipping sensation, as if I’m sightlessly grabbing for a greased rope, even though the tail end of it has already gone flickering beyond my grasp. The only way to mark the passage is by the sudden slam of credits at the end of an episode—something which should presage a loosening, a relief, but which only ever feels like the grapes on their bendy branch, its bough lifting away from Tantalus’ questing fingers. Of course it’s a cliffhanger. I am losing my grip.

Another episode begins. The golden letters proclaiming LOVE IS BLIND animate over the skyline in a haughty sans-serif, then glint with a lens flare, reminding me of the opening titles to a soap opera. Of course I must continue to watch. I must know what happens to the hapless woman that has pinned her marital aspirations on a man who appears to exhibit alarmingly psychopathic tendencies. Perhaps this is not his fault. Perhaps it is what my friend Chelsea calls the “villain edit,” which is done in post-production by the wizards cutting and sewing the scenes together. Perhaps this detestable-seeming individual was unfairly maligned by the editors’ need to present a cohesive narrative—a rise and fall, a ritual which would include chalking the shape of Freytag’s Triangle on the cutting room floor.

Later, in a scene like a Dollar General version of The White Lotus, the couples come together during a vacation in Honduras, for kebabs and drinks, still bearing aloft their gilt goblets, like a bizarre tableau from a Tarot card. In some scenes, couples are isolated to show us flashes of their infatuation as it melts slowly off the bone in the face of such deal-breakers as snoring, bathroom habits, and sexual exploits. The camera trains on these new couples as they relentlessly analyze (or attempt to) relationships that sprang from a well of artifice. Constant self-referential commentary peppers the conversations, punctuated by the torpid smiles of the show’s hosts, Nick and Vanessa Lachey. (You may remember Nick Lachey as the anchor frontman for a boy band—98 Degrees—back in the 90s, itself a copy of a copy, already suffering from generation loss even before getting a radio hit.) It is the Lacheys, too, who introduce us to the next phase of the “experiment”—the new couples are to move in together, turning their attention from peccadilloes to zones of true contention: finances, work/life balance, and integration into their “real lives.”

“I’m living with my fiancé—I’ve moved in with my fiancé, who I have known for three weeks,” exclaims one of the women to the camera in a brief confessional, breathless with both the infatuation of the new relationship and also with the sheer audacity of the circumstances. “This is crazy” turns into “this is so weird” turns into long silences, watching the eyes of each go anywhere other than where the other’s voice is issuing from. Even the briefest of glances pings off their significant other like a bead of hail in a winter storm, and goes ricocheting across the room with the same force.

Then comes a new development: meetings with their respective families. Inexplicably, the golden vessels travel with the contestants to these—even spreading into the hands of their parents and siblings. They lift the drinkware uncertainly to their lips, perhaps just to mask their confusion, as their loved ones profess undying love for virtual strangers. During these sometimes fraught sessions, the language abruptly changes; it’s no longer an “experiment,” it’s the “process.” Family members, not previously part of the show, start to echo these terms, often tremulously, within the greige confines of their Midwestern living rooms. And everywhere, the golden vessels follow them—even to the tables at anonymous, transitory public spaces like coffeeshops or bars, all of which are inexplicably unpeopled, except for the focus couple and the parent in question, of course.

I feel vertigo starting to tilt the room. Everything in my vision is tunneling, funneling, toward the bright square of the television, flickering in a seductive rhythm. I can’t seem to keep up with it.

One of the women is confessing directly to the camera. She mentions that her fiance went out the night prior to meet up with a group of others. She calls these others “pod people.”

It takes me a full minute before I realize she isn’t referring to uncanny alien replacements, but the other contestants from the “pods,” those who remain—sadly—still unmatched.

“Time isn’t real,” says one of the contestants. Their voice drifts out of the television, flat, with no reverb. I can hear the roughness of their vocal fry as they try to explain what they mean. It makes the speakers crackle and vibrate with discomfort.

“There’s no divorce in this family,” intones a mother of one of the contestants—darkly, and with no small amount of threat limning the statement.

Despite the banality of the scene and setting, Chelsea’s cats both bolt upright from their somnolent coil and stare in opposite directions, as if startled.

It’s impossible to tell what’s frightened them.

I realize abruptly that it’s past midnight, and my drink is gone. I’m pretty sure when I started, I was drinking out of a pint glass, but now it has inexplicably transmogrified into an exact replica of the golden vessels I see on the screen. The ridges of the brushing effect on the metal seem to fit congruently into the whorls of my fingerprints. I’d look into it, to see what’s within, but I’m afraid of what I might see, so I keep my eyes on the screen.

Another family meeting, with a different prospective couple. “I think we were like, ‘Oh, this is funny,’” the relative says, describing their reaction to the engagement. Then, she continues. “Now, ‘This is not funny, This is real.’”

The contours of the living room are hazy, at best, in this dim light. I swear I can see every pixel on the giant television, easily as wide as I am tall. The faces are larger than my own. I think about an article I read once about Zoom calls as a trigger for adrenalin, being confronted only with big faces projected on a screen in front of us. The walls around the edges of the television have become fluttery and smeary.

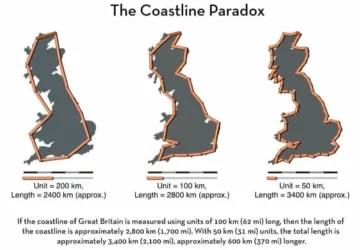

I think about the coastline paradox—how the more precisely one measures, the more it only adds to the total. Borders and boundaries are never what they appear to be. The lines on a map indicating where one place ends and another begins are completely arbitrary. An intertidal zone is in constant flux. Waves of static erode the shore of reality.

“Us talking back in the pods,” says a contestant, her voice quavering with restraint. It’s hard to tell if it’s staged. “No distractions, literally just us.” It’d be easy to believe her yearning for that kind of intimacy. It sounds like she, herself, believes it. I might even believe it. I’ve seen enough of her now that my brain probably produces oxytocin when she’s onscreen. Her eyes are huge, watery. I can see the color of them moving and shifting from a greenish-brown to golden—a mirror of the mug she holds in her hand: dull, burnished, metallic. “And then, classic, when we do come back to the real world, it’s all … hitting us.”

The real world they speak of is the one of chattering over-convenience, of hyper-connectivity. They long to return to the insulation of their pods, blinded, ignorant to reality, their only companion a disembodied voice telling them everything they want to hear. They long to disconnect, to return to their womblike pods, seen and not seen simultaneously.

I’m reaching, now, for the remote.

My headache has grown stronger, and I yearn for the sweet oblivion of darkness to banish the flickering pixels from my vision. If not to shut off the television, to at least change the channel. I, too, wish to disconnect from this gross depiction of “reality.” The carelessness with which these people treat one another is monstrous, and all their acts are conducted under a false aegis of sincerity and authenticity.

Finally, the remote is within my grasp. Onscreen, the putative brides-to-be are gasping and fawning over one another’s gowns. Veils are affixed. “It looks so much better with the veil,” comments a relative, her expression mottled and tear-stained.

Will they? Won’t they? These are the two questions that most television is predicated on, the axis of connection, the broad beam for every romantic insecurity and selfish desire.

I’ll never know. The television seizes like an spasming eyelid, goes blind with one poke of the POWER button.

I hold my breath. For long moments, I can see nothing. My ears prick to the smallest sound—one of the cats, discomfited by the sudden change in atmosphere, has begun to purr—desperately, loudly. It’s all I can do to stop myself from trying to note the frequencies of it, as if she is attempting to send a message in Morse code. A few moments later, the other cat makes a querying mrrrow? and I hear the patter of her little feet on the floorboards, skittering off into the kitchen.

My eyes have adjusted now to the semi-darkness, and I let my gaze float to the nearby floor lamp, unlit, shrouded in shadows. I think of Thomson’s paradox—if a lamp is switched on and off an infinite number of times, is it considered “on” or “off”?

Onscreen, the bride is standing at the altar. The officiant is reminding her that this is the Big Day, the Moment, when they—as well as all of us in the audience—will discover if love truly is, in fact, blind.

But I’ve turned off the television, haven’t I?

Am I asleep

Is this a new spin-off of Love is Blind, called Love is a Dream?

Have I been chosen to audition? How did they get my contact information?

I squint at the blurry, fractalized edges of the television screen.

Is that … a camera?

Is that … me, behind it—my face, obscured by the camera’s unblinking glass eye?

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.