by Herbert Harris

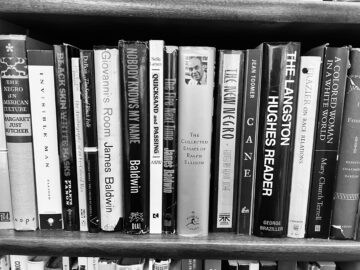

The greatest privilege of my childhood was growing up in a house where books had their own room.

My father’s library occupied the second floor, the only room without a window air-conditioning unit. On summer afternoons in Washington, DC, when the heat and humidity pressed down like a weight, the rest of the house hummed and rattled with machines straining to keep up. The air in the library stayed stubbornly still. It was the early 1970s, and I was on summer break after tenth grade, retreating there to find the peculiar solitude this room alone offered. Each book I opened sent up a cloud of dust that glittered in the angled sunlight. Shutting the door turned the room into a sauna, but in that quiet stillness, I didn’t mind. It felt like the price of admission to a different world.

The previous summer had unfolded differently. I had just finished ninth grade, where we surveyed the classics of English literature and retraced the decisive moments of Western civilization, reliving the deeds of its great men and women. I spent long afternoons in the library, sinking into those books as the heat pooled around me. I melted into a reclining chair and wandered through the past. That immersion had felt complete, even sufficient. But this summer, I arrived with a different appetite. I was growing skeptical of the Eurocentric narratives threaded through everything I was learning. I sensed there were other stories and vantage points, and I came looking for them.

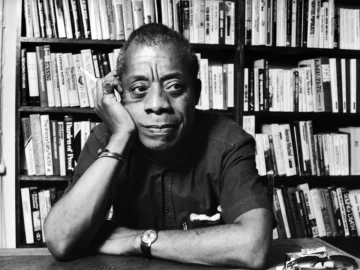

I picked up the book I had been reading a few days earlier and turned to the page marked with an index card. I searched for the sentence I remembered, but at first the words slipped past me. James Baldwin was writing about a Swiss village, about children shouting “Neger” as he walked through the snow. Seeing the word on the page registered instantly, not as surprise but as recognition. I had learned early what it meant to be called that name in its American form. That knowledge had settled into my body long before I could articulate it. Read more »