by Scott Samuelson

Though universities have traditionally been associated with educating students, I don’t think that it makes sense anymore. There’s too much at stake.

Education requires wonder, discipline, personal attention, liberal learning, standards, mentorship, transformation, reading. Let’s face it. These things don’t scale well, especially when it comes to generating the revenue universities need for their survival or economic growth. The jobs of not just professors, chairs, administrative assistants, provosts, and presidents are on the line—also deans, student life directors, recruitment officers, assessment coordinators, and usually associate and assistant versions of all those positions, among many others.

Maybe it was feasible for universities to aim for education when they received more public funding. But those days are over. Few people care about being an educated person, let alone about educating the populace at large. Plus, most people—even many in the university itself—don’t distinguish between being educated and being trained for a job.

But universities shouldn’t just focus on research and jettison teaching and learning altogether. The revenue stream of students is too vital.

Universities should attract students with what they really want: concerts, sporting events, gaming stations, food courts, swanky dorms, fewer requirements, and so on. (At the same time, it’s savvy to put fees on some of these goods to generate more revenue for the university.) But the university shouldn’t just be an expensive four-year resort experience. There needs to be a value-add that justifies public support and the increasing cost of tuition and room and board. The ostensible value of the university needs to involve credentialing students for successful entrance into the economy.

The beauty of a credential is twofold. First, money. Universities should drive home that a credential is a ticket to a well-paying job. Second, status. If disciplines like the arts and humanities have any value, it’s to equip students with moral and political vocabularies that socially elevate them above the uncredentialed. That way, even if by chance a plumber without a college diploma makes more money than a university graduate, the credentialed will have the consolation of looking down on the plumber. Read more »

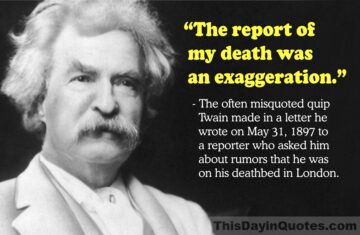

Noam Chomsky was rumoured to have left us almost a month ago, but he always

Noam Chomsky was rumoured to have left us almost a month ago, but he always