by Mark Harvey

There was a time when the West was truly wild. I don’t mean the gun fights in saloons, the stampede of a thousand cattle, or stagecoach robberies on the high plains. But it wasn’t that long ago when every river from what is now Kansas to the Pacific Ocean ran its course without a dam or diversion, tens of millions of buffalo grazed on the rich grasslands, and beavers built thousands and thousands of ponds across the Rockies. It was but a blink of the eye since apex predators like Grizzly bears and Wolves ruled the land from north to south.

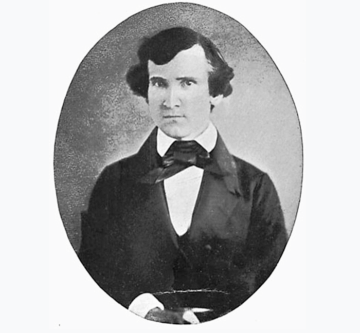

One man who witnessed a nearly virgin West was John K Townsend, the first trained naturalist to travel from St. Louis to what is today Oregon. In a book called Journey Across the Rocky Mountains to the Columbia River, Townsend shares images of a trip that began in 1834, not long after Louis and Clark first made their expedition. Even in bustling St. Louis, where Townsend was provisioning, there were foretokens of what was ahead in the untrammeled country he was to cross. He describes the sight of a hundred Saque Indians with shaved heads and painted in stripes of “fiery red and deep black, leaving only the scalping tuft, in which was interwoven a quantity of elk hair and eagle’s feathers.”

Just a month into the trip, Townsend encounters a trapper who tells the story of having his horse and rifle stolen by Otto Indians in the middle of winter while still far from any settlement. When Townsend asks the trapper how he survived without food on his journey home, the trapper says, “Why, set to trappin’ prairie squirrels with little nooses made out of the hairs of my head.”

About six weeks into the crossing, Townsend describes the various wolves slinking about the camp looking for scraps of food. By his narrative, he does not seem a bit afraid of them but describes the encounters as “amusing to see the wolves lurking like guilty things around these camps seeking for the fragments that may be left.” The contrast of this naturalist’s comfort around wild animals camped out in the true wilds with just a horse, compared to some of today’s self-styled “mountain men,” is stark. For if you turn on most any AM radio station in Montana, Wyoming, or Colorado today, you’ll hear angry men sealed in 6,000-pound pickup trucks on major highways, calling in to talk shows to express their fear and loathing of wolves. My how soft we’ve become.

There are still some vast open spaces that have barely been touched but today’s West has been plowed, paved, plundered and over-tamed. Most every river in the Intermountain and coastal West has been adjudicated, dammed, or diverted. Apex predators like the grizzly bear and the wolf have been reduced to the point of near extinction and vast swaths of public lands have been fenced and overgrazed. What was once the Wild West is today the Wounded West. Our modern journey is no longer Manifest Destiny, but instead should be something like Manifest Renewal or Manifest Redemption.

The term Manifest Destiny, the idea that Americans would naturally and inevitably conquer the western half of North America is attributed to John O’Sullivan, a columnist and editor for The New York Morning News. He first used the term in an 1845 editorial urging the US Government to annex Texas. In the same year, he used the same term to urge the government to claim the entirety of Oregon, stating,

And that claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.

Thus the push west and the fierce expansion of white settlers was guided both by a hunger for land and a romantic and religious sense of Providence.

In the last few decades, we have taken stock of what’s been done to the land, water, plants, and animals, and measured what remains. There are some hard truths we have to face: we didn’t understand the patterns and rhythms that sustain life across a dry land and in the rush to tame the West, we nearly destroyed it.

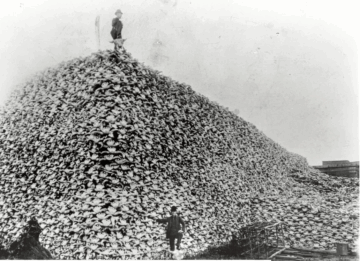

The butchery wrought on the landscape in seeking our Manifest Destiny is not something any of us wish to revisit. Most emblematic of that butchery was the killing of close to thirty million buffalo in a period of fifteen years. There have been many accounts of the giant herds of buffalo roaming the West in the 19th century, but Townsend’s description of a herd he and his companions encountered in what is today Wyoming is one of the most vivid. Roughly two months into his trip and near the Platte River, they ran into a herd extending miles long and miles wide. He wrote,

Towards evening, on rising a hill, we were suddenly greeted by a sight which seemed to astonish even the oldest amongst us. The whole plain, as far as the eye could discern, was covered by one enormous mass of buffalo. Our vision, at the very least computation, would certainly extend ten miles, and in the whole of this great space, including about eight miles in width from the bluffs to the riverbank, there was apparently no vista in the incalculable multitude. It was truly a sight that would have excited even the dullest mind to enthusiasm.

To bring the buffalo to near extinction with Remington rifles in just two decades eludes all reckoning.

Townsend was quite taken by some of the Indians he met on his journey and he describes them with reverence. Shortly after seeing the vast buffalo herd, he meets some Pawnee men who had been invited to spend the night in the camp by the expedition captain. He writes,

These Indians were the finest looking of any I have seen. Their persons were tall, straight, and finely formed; their noses slightly aqualine, and the whole countenance expressive of high and daring intrepidity….I know not what a physiognomist would have said of his eyes, but they were certainly the most wonderful eyes I ever looked into; glittering and scintillating constantly, like the mirror glasses in a lamp frame, and rolling and dancing in their orbits as though possessed of abstract volition.

To be sure, not all encounters with Native Americans were so friendly, but it is painful to consider the debasement and annihilation the US cavalry wrought upon so many Western tribes. From the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado to the Bear River Massacre in Idaho, the cavalry wiped out entire villages sparing neither women nor children. It’s not to say that Indians didn’t fight back with skilled ferocity: just read Empire of the Summer Moon if you want to get a feeling for Native Americans’ will to survive. They were as tough as any humans to walk the earth and fairly merciless in battles and retribution. The image of them as peaceable peoples living rainbow lives without fighting on the prairies and mountains is patronizing and does them no service. When it came time for war, no people were more warlike.

There are many other things done to the West that can be seen as quiet massacres. To satisfy a fancy for felt hats in Europe, men trapped tens of millions of beavers taking the species to the brink of extinction. Stockmen, seeing vast grasslands entirely for the sole purpose of fattening cattle, eradicated apex predators such as the wolf, the mountain lion, and the grizzly bear. Engineers dammed and diverted billions of gallons of water, drying up rivers and wiping out fish populations.

In short, we have asked more of the land than the land has to give. We are nearly at the point where what’s left of the Wild West is the portrayal of a cardboard cutout stockman and his super dysfunctional family in the smarmy television series Yellowstone. No one wanted to like Yellowstone more than I did, but alas, the show is nearly unwatchable.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that there are dozens of organizations trying to heal the land, protect imperiled species, and really learn the patterns of the wind, the water, and the seasons.

Start with beavers. Who would have ever thought a chubby, buck-toothed animal that is almost incapable of walking on land would become a hot commodity in the wildlife kingdom? But beavers are all the rage in the world of biologists and ecologists now that their capacity to build lakes and wetlands and purify water has been understood. In Oregon, the state legislature has passed HB 3932, prohibiting commercial and recreational trapping on federal lands in impaired watersheds. California passed AB 2196 a bill that seeks to bring back beavers to watersheds they once inhabited. The US Fish and Wildlife Service has written a Beaver Restoration Guidebook to help landowners and land managers use beavers in wetland and floodplain restoration.

Even with his roaming mind and imagination, Townsend couldn’t have possibly imagined that one day elk, deer, antelope, and bear would be trapped into small blocks of habitat by roads and highways from New Mexico to Montana. Since the car wasn’t even invented and the fastest stagecoaches went less than twenty miles per hour, the idea that thousands of big game and apex predators would be killed by speeding automobiles as they traveled through feeding grounds would be science fiction to the naturalist. And yet every highway shoulder in the Intermountain West is littered with the carcasses of wild animals.

We will never get back the great corridors where pronghorn or elk traversed but citizen groups across the West are endeavoring to build overpasses and underpasses so that fewer of our glorious animals will meet the speeding Audis and Mack Trucks ripping down the roads. Building an overpass takes years of planning, coordination between counties, states, and private landowners, and generally costs millions of dollars. But they work.

And they are being built, one after the other. Who would have thought that Nevada, that state with 140 thousand slot machines, would be leading the way with wildlife crossings? And yet the state has built six major overpasses and 80 dedicated wildlife crossings. As an aside, Nevada is also very good at water conservation and has the largest herds of wild horses in the United States.

Colorado, California, and Montana are also doing all the tedious behind-the-scenes work to give their wildlife a fighting chance with built crossings.

For Native Americans, the journey to rebuild their cultures after decades of cruel abuse has been a crossing of rough country. I wish I could say that the surviving nations have rebounded smoothly and their peoples are living lives of peaceful abundance. But for so many Indians across the West, it is still a great struggle, and neither the federal government nor state governments have done much to make things better. However, the spirit hasn’t died and there are bright lights like the appointment of Deb Haaland to be Secretary of the Interior during the Biden Administration. There are great writers such as William Least Heat-Moon and the late Scott Momaday bringing us the worldview of their heritage. Members of the Chicksaw, Ho-Chunk, and Choktaw nations hold seats in the US House of Representatives.

One of the strongest symbols of Indian revival is the recent removal of dams on the Klamath River. Over many years, a consortium of tribes, including the Yurok, Karuk, Klamath, Hoopa, Shasta, and Modoc, worked to have the dams removed, and last year they won that battle. It has opened up 400 miles of salmon habitat and in some ways rejoined the Native American communities living along that grand river. The salmon are returning and with it, we can hope, a stronger sense of identity and pride among the river’s people.

Finally, there are the apex predators such as grizzly bears, wolves and mountain lions. All three species have been on and off the endangered species list, vilified, poisoned, shot, and run down mercilessly by snowmobiles. Stockmen in particular hate apex predators and did their level best to eradicate them last century. Like our understanding of the beaver, we’re finally understanding the crucial role that apex predators play in governing everything below them on the food chain. They don’t just control populations of ungulates, they cull out the sick and the weak, ultimately making the herds stronger and more resilient. And they don’t just change numbers, they change behavior. Wolves, for instance, keep elk out of riparian areas, giving our chubby beavers a better chance at building vast wetlands. Great wetlands mean better fisheries and more songbirds. You get the idea.

Here in Colorado, a ballot initiative to reintroduce wolves won by a slight margin and a few wolves have been brought in from Oregon and British Columbia to reinhabit the Rockies. It has been a somewhat rough beginning with the wolves killing some cattle right after reintroduction. As a rancher myself I studied the issue carefully in the states of Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho where wolves have been roaming the last 30 or so years after the reintroduction there. I’ve spoken to ranchers from those states who have learned to deter wolves from killing their livestock and some have even come to admire them. Since the reintroduction, wolves have been crossing my ranch without incident. I believe, with time, we can also learn to live with them and that they will improve Colorado’s delicate ecology. You know what kills far more livestock than wolves: domestic dogs.

I love the West, and I love what wild qualities it still holds. I honestly feel safer and more at peace in the Utah badlands and the Book Cliff Mountains than I do in the most coifed landscapes of Connecticut or Florida. It’s difficult to put into words, but the West is both rustic and delicate, intimate and indifferent, gentle and unsparing. Manifest Destiny never meant we were called to destroy half of what once lived here and spoil its charm. What is manifest upon us today is to heal and bind up this great land. That is our destiny.