by Steve Szilagyi

by Steve Szilagyi

You don’t need to be told that Halloween yard decorations have gotten tackier over the years. Complaining misses the point. Their jokey vulgarity is the point—as if America in 2025 were so buttoned-up that people need yet another occasion to act out their bad taste in public.

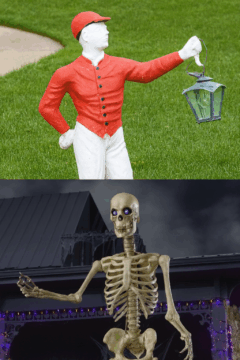

Front lawns have always been small stages where homeowners perform belonging. A generation ago, lawn jockeys did the job; now it’s perfect turf and pruned boxwoods, silent signals of order and disposable income. A good yard says: we’re respectable, we fit in.

So, what do the gravestones, twelve-foot skeletons, and dangling corpses say?

Holiday decorating is contagious. One house hangs Christmas lights, and by next year the whole block glitters. Studies even show that people who decorate for the holidays are seen as friendlier and more community-minded—more neighborly altogether.

David J. Skal writes about Halloween and its customs in his entertaining 2002 book; Death Makes a Holiday. There, he tells of a couple in Des Plaines, Illinois whose Halloween display grew to include a guillotine, a blood fountain, and forty life-size monsters, until traffic jams forced the city to shut it down. “We were just trying to do something fun for the neighborhood,” the wife said as she dismantled the blood fountain.

Most homeowners aim smaller: a few plastic tombstones, a skeleton or two, ghosts dangling from trees. Some add comic epitaphs or political jokes—tombstones for Inflation, Common Sense, or TikTok—but the results rarely rise above the store-bought gag.

Halloween is supposed to be the one night suburban order loosens its tie. Yet the displays themselves are oddly regimented. Creativity, such as it is, lies in how many clichés you can stack on one patch of sod.

Skal notes that nearly every “tradition” we associate with Halloween dates only to the early twentieth century. The modern holiday took shape in the 1930s; even the jack-o’-lantern arrived late. Older customs like door-to-door begging once belonged to Christmas or Thanksgiving. What does reach back centuries is mischief—fire, vandalism, breaking things. Halloween rituals like candy-collecting and apple-bobbing were invented to tame that chaos.

If the twentieth century domesticated Halloween, the twenty-first has industrialized it. Home Depot kicked the Halloween yard display into a higher gear with the introduction of “Skelly”, its menacing 12-foot plastic skeleton. The first time I saw one, it scared the pants off me. Now they’re as common as birdbaths. You wonder where people store them—and what they think they’re saying now that everyone else has one too.

Home Depot’s success with its skeleton inspired it to create an army of giant horrors. These include a twelve-foot figure of hooded death, with a glowing skull and motorized jaw. The website reads, “Levitating Reaper. Six spooky phrases. Seven color options.” Price: $299.

One of these grim reaper figures was recently installed (alongside giant skeletons and witches) on the front lawn of a mansion in one of our wealthier suburbs. Not far away house is another mansion that was the site of an awful tragedy: a domestic incident led to the murder of an entire family. Neighbors heard the screams and gunshots. It was a street I drove down every day on the way to work. You’d think that the horror of those killings would have sobered that street for good. But Halloween came along within a few months of the tragedy, and with the cries of the innocents still figuratively echoing, witches, skeletons and gravestones rose from a few nearby lawns as if nothing had happened.

And now, with some years having passed, this mighty, grinning effigy of death stands watch over the street – cheerful as ever, its eyes changing color through the night.

Is this sheer cluelessness—or something darker? Do these giant figures tap into a psycho-religious yearning so powerful that even wealthy, well-educated suburbanites feel compelled to put their gods on display, against all good taste and common sense, on a street where the cries of dying innocents still figuratively echo?

Do these people know that death is not a fantasy trope like wizards, it’s real and it will come for them and everyone they love?

Making an idol of death aside, there are other ways for Halloween displays to offend. Not far from where I live, a well-to-do homeowner shocked the neighbors by putting what appears to be a homeless encampment on his landscaped front lawn. There are three domed tents with figures dressed in shabby clothes emerging from the tents’ front flaps. A half a dozen other life-sized figures sit in chairs or appear to mill about in the stiff postures of drug addicts. What appears to be litter hangs from the neat shrubbery (it’s not litter but that stuff that is supposed look like spider webs) and for some reason, the whole scene is surrounded by yellow crime scene tape.

When I first drove past the display, I nearly choked, thinking it was real. The tents stand just down the hill from the high gates of the town’s most exclusive country club. For a split second I thought a real homeless encampment had sprung up in the shadow of the ninth hole. Then common sense reasserted itself—the local constabulary would have dealt with that, toot sweet. Then I guessed that it must be a message directed at the country club elite: a righteous homeowner protesting wealth inequality and exclusion. But if you look closely, there’s a sign that, when you slow down to read it, disabuses you of the hope that there’s some higher purpose here. The sign says, “Camp Crystal Lake”. The display is a tone-deaf Friday the 13th reference—a little diorama of a slasher movie.

You see all sorts of puzzling things in our town. One house, sitting right beside an actual cemetery, set up plastic cartoon tombstones not a dozen feet from real ones. The imitation dead, it seems, are easier to live beside than the real kind.

And in that same cemetery, I came across a new granite headstone incised with the Batman logo where you’d expect a cross or Star of David. You could argue that all religion mixes death and fantasy, but if that guy thought Batman was going to save his immortal soul, he’s in for a surprise.

“Despite a vast landscape of tombstone-decorated lawns, make-believe haunted houses, and the endlessly replicated jack-o’-lantern grin,” Skal writes, “Halloween in America has always had difficulty dealing with the reality of death.”

That tension runs through Death Makes a Holiday, which ends with a chapter on the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the October 31st that followed.

Surely there will be no Halloween this year, I remember thinking at the time. For heaven’s sake, let them call it off. The real horrifying images—the severed hand on the sidewalk, the recordings of phone calls from soon-to-be-dead office workers, the plumes of flames, the ghostly, soot-covered figures wandering through smoke and dust—wasn’t that enough death for you? Apparently not.

As Halloween approached, suburbanites turned off their TVs, went out to their lawns, and set up fake tombstones, spider webs, and coffin lids as if they had no idea what death actually was.

Even places steeped in real death can’t resist the ritual. When I worked at a hospital years ago, the emergency-department nurses decorated their lobby every October and invited pediatric patients down for candy. The lobby became a mock graveyard—paper tombstones, dancing skeletons, cobwebs. The nurse who was showing me around said, “We usually do more decorating. But we were so busy yesterday. Three codes in this room before 11 am.”

Then the children came shuffling in, each carrying a trick-or-treat bag. Many were near-skeletons themselves, since only the most seriously ill children are hospitalized these days. Some were in wheelchairs or pushing IV poles. There were children bald from chemotherapy, children who could barely muster a weak smile as they watched an EMT dressed as Dracula drops Kit-Kats into their sacks.

“Against the the evil of death there is no remedy in the gardens,” says an old proverb. “Death devours lambs as well as sheep.”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.