by David J. Lobina

One of the most annoying aspects of living in an American – that is, US – world is not the imperialism of it all, with US military bases in hundreds of countries and the many wars and unpunished war crimes that have come with these bases in the last 80 or so years (and let’s not forget economic warfare, of course).[i]

Nay, the worst thing about an American world is the cultural hegemony that stems from the immense soft power the US yields in the world and that we, as regular citizens of overseas countries, must endure. This is especially annoying when it comes to political and cultural discourse that is clearly specific to the US, and to US social and political conditions, but which often becomes, in a blink-and-you-miss-it kind of moment, almost universal.

I say ‘almost’ because the effects do not always hold for long, especially in non-English-speaking countries, but some issues, along with particular ways of approaching these issues, do sometimes become common talking points outside of the US, and often for longer that is merited. A case in point is the meaning and usage of three political concepts that originated, in each case, in Europe, but which have received different (and, sometimes, very different) interpretations in the US, with some of these new readings coming back to Europe in a new incarnation, with various levels of success, but sometimes replacing the original interpretations – even if there is typically little justification for this to happen at all.

The three concepts I want to discuss here are liberalism, libertarianism, and once again, but this time rather briefly, fascism, and my flippant conclusion will be that Americans should be a little bit less colonial and leave our word-concepts alone!

Let’s start with liberalism, the most common of the three, but a term that is used in a variety of ways everywhere you look in the world (no comprehensive review will be attempted here, naturally). From an etymological point of view, the word liberalism, in English, was possibly borrowed from the French libéralisme, from the early 19th century, whilst the word liberal, either as an adjective or a noun, was in use much earlier.

As an adjective, the Oxford English Dictionary lists two relevant meanings of liberal, both from the 18th century: said of a person who favours social reform with a degree of state intervention, and said, also, of a person who supports individual rights and civil liberties, with a view to advocate individual freedom but with little state intervention.[ii]

As a noun, and perhaps more interestingly, the OED gives us 4 relevant connotations of the word liberal: a) political or social reform tending towards individual freedom or democracy; b) in Europe, and starting in the 19th century, it was a reference to anti-monarchist parties in France and Spain, whilst now it can refer to parties that sit between socialism and conservatism; c) in Britain, the OED lists some quotes from the 19th century where the word is closer in meaning to the European sense just outlined above – and, thus, to European radicalism, as discussed here, which in turn I discussed myself, briefly, here – but more properly it referred to the Whig Party (now, after some transformations, the Liberal Democrats), a party that moved from the defence of individual rights and freedom from the state at its inception to advocating actual state intervention under its current guise; and d) in the US, and from the 19th century, it is often used as a synonym for socialism, but as a slur.

As for the word liberalism, the OED lists two pertinent readings, both originating from the early 19th century: a) support or advocacy for individual rights, civil liberties, and reform towards freedom and democracy; and b) left-wing political views or policies. And if we move to a more continental Europe context, and in particular to the Italian and Spanish languages (my other two languages), the relevant dictionaries gloss the word liberalism (well, liberalismo) as referring to individual and social freedom, in the political context, and to private initiative with little state intervention, in economic and cultural contexts.[iii]

That’s as far as the dictionaries go, but it is already noteworthy that the continental definitions don’t quite separate the economic and political senses within the meaning of liberalism quite as much as the OED does – there are no separate entries in the Italian and Spanish dictionaries – though the general ambiguity naturally remains in any case. After all, a self-description such as ‘I’m politically conservative but socially liberal’ (or the other way around) is not uncommon in Europe, and whilst it is often unclear what is meant by this without further elaboration, no-one would claim that the usage is unwarranted or in error.

More to the point of ideas and concepts, and to offer the just-requested further elaboration, there is often a distinction in the literature (see my discussion on Bobbio vis-à-vis the left-and-right divide) between social liberalism, which calls for a regulated market, the expansion of civil and political rights, and works towards a common good over individual interests (but it is not socialism, for capitalism is not contested) and economic liberalism, which calls instead for limited government and laissez-faire economic policies (the latter is often called classical liberalism, but the latter is a retronym).

Crucially, it is the economic kind that is usually meant in continental Europe when someone uses the word liberalism, and not the social kind, as for the latter the expression social democracy is more common in European discourse (or sometimes just some reference to progressive policies; social democracy is close to socialism in aspiration, at least historically). This state of affairs, as it happens, was also more or less the case in the US, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, until the early 20th century, where ideas around social programmes became mainstream during the New Deal years, and ever since then the word liberalism has been associated to welfare-state policies in the US, what Europeans would simply call social democracy (see here for more on this, including an explanation as to why someone like Bernie Sanders is a social democrat rather than a socialist; Chomsky has made the same point in the past regarding Sanders; cf. this, though).

So, when Donald Trump says that he likes the current Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Kier Starmer, even though, says Trump, Starmer is a liberal, what he must mean by this (I guess!) is that Starmer believes in welfare-state policies, progressive politics, and the like, and clearly not that Starmer is a classic liberal, in the economic sense. As such, Trump’s description is a rather ill-fitting one, for Starmer is a Blairite, New Labour kind of person – and, thus, he is hardly a social democrat, let alone a socialist. Indeed, Starmer’s government has tried to reduce the welfare state significantly since taking office, as Blair’s governments did too (the description applies more aptly to the Liberal Democrats, as mentioned).

Tellingly, some of the European politicians that Trump can count as allies unambiguously and unproblematically call themselves liberals tout court in their own language and in the context of their national politics, and what they have in mind when they do so is the economic sense of liberal, and not the social sense that Trump so despises. It is also true, however, that in an international context most Trump allies in Europe these days actually avoid the word liberal altogether, sometimes denigrating liberalism in general as much as the Trumpistas do (see, for instance, Orbán on this), and this is just an example of the general phenomenon I am describing – from the particular in the US to the general worldwide. There is a disassociation in the air is what I am saying![iv]

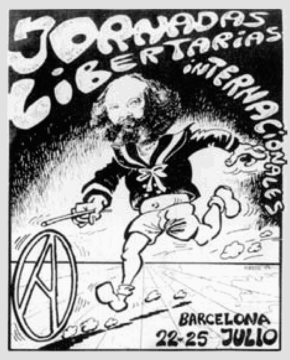

A more egregious example of such a disconnect involves the concept of libertarianism. According to the OED, to start here again, the word libertarian, attested from the late 18th century, initially referred to the doctrine that human beings possess free will, it then became a reference to a defender of liberty in political and social spheres within the anarchist tradition, and then in the 1940s, and in the US only, it became associated to a doctrine regarding the protection of individual rights, the operation of the free market, and the minimisation of the role of the state – a kind of politics squarely on the right. As for libertarianism itself, the OED contains three connotations: a) the human-beings-have-free-will doctrine, from the 1830s; b) advocacy for the exercise of liberty, with most references dating from the 1890s, and almost exclusively from the anarchist literature; and c) the aforementioned reading of the concept in US politics from the 1940s.

If we move to continental Europe, or rather, to the Italian and Spanish languages, libertarian and libertarianism refer almost exclusively to anarchism – with the latter sometimes referred to as libertarian socialism, in fact. Here Wikipedia comes in handy, especially when it comes to comparing different language versions: both the English and Italian pages make clear that libertarianism has mostly been a concept associated to a form of anarchism prior to the 20th century, when in the US, and in the US alone, to stress the point, it came to be associated to right-wing politics and capitalism (the Spanish version seems to be based on the English page, but bizarrely it has changed the order of exposition, with the bit on anarchism not appearing at the beginning but towards the end, thereby yielding a misleading view).[v]

As it stands, then, libertarianism is an exclusively capitalist idea in the US, and hardly anyone there would associate it to socialism or communism (anarcho-capitalism is another typical American invention here). The influence of such usage has been stronger in English-speaking countries, where the anarchist/socialist reading has all but been lost by now, including in the UK (except, of course, in the anarchist literature, but this is clearly the minority usage now).

This was clearest to me when I was studying philosophy in the UK in the early 2000s. In a political philosophy class, there was a lecture devoted to libertarianism, which I had earmarked from the beginning, given my interest in…anarchism! To my surprise, the lesson was devoted to what seemed to me nothing more than a family of theories defending unbridled capitalism, including a class discussion of a paper entitled “Is left-libertarianism a coherent concept?” (or something like that), written by the very same lecturer who was in front of us, and the whole scene did not compute in any way for me – no aspect of the lecture or the subsequent discussion proved to be coherent for me at the time.

Where was, I thought, the whole Chomskyan take on how libertarianism (that is, socialist anarchism) is a development of liberalism, with Wilhem von Humboldt’s book, The Limits of State Action as the main example to discuss?

I was clearly new to a discourse I did not know existed, but I soon realised this was pretty much a US phenomenon, even if it had made some inroads in the UK, at least in academia (academia itself is heavily dominated by US universities and scholars, of course). Soon after this realisation, I was more attuned to what was going on; when a Facebook contact chose libertarian among the list of options Facebook used to provide regarding one’s political orientation, for instance, I was aware that US soft power was at play – here was an American company not bothering to change the user options for an international audience, simply assuming that their terms of reference were universal (my contact, by the way, did not own up to their beliefs when I enquired about it; they said they thought they had selected “librarian”; he was not a librarian, but a banker). There were a few contacts from Italy or Spain espousing capitalist-libertarian ideas too, but these were a minority, their references were exclusively American (they would always start with Milton Friedman and end up with Murray Rothbard), and they were clearly and completely out of place in European discourse.

But still, in English-speaking countries I simply cannot talk about libertarianism and assume my interlocutors will interpret this concept as a reference to a kind of socialist anarchism.

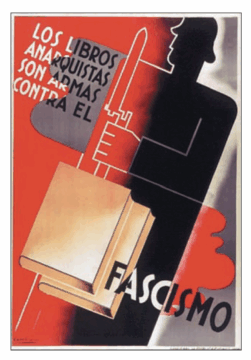

And now, briefly, on to fascism. Not to labour the point I have made before, and not to be a bore, but: ah, I was just teasing, just go and read my posts on it here, here, and here.

*****

This is just a sample, and there are many more examples of the general phenomenon I have discussed here. This phenomenon is clearly also true of many social ideas and movements that did start in the US, were then exported to other parts of the world, spreading like wildfire over the internet (and of course the internet itself is also controlled by US companies), but which in the end are oftentimes and simply not applicable in other places. In the context of European social conditions, my focus here, certain strands within the Black Lives Matter movement or Critical Race Theory, for instance, have proven to be rather inapt and have produced little of substance, and in the end importing them into Europe has been the result of projecting particular aspects of American history onto all of humankind, as John Gray has put it (this could have been the title of this post, in fact). There are other examples worth discussing, such as the American preference for equity over equality, and the spreading, again, from the US, of so-called gender identity politics, which has had a terrible effect on academic philosophy, for instance (see here, for philosophy; and here for the sad state of affairs regarding discussion around sex at UK universities). But this is for another post!

In the meantime, do give us back some of our word-concepts, Americans!

* But do keep Jason Stanley, though.

[i] I’m kidding, of course: US imperialism is the worst thing about living in an American world.

[ii] In a non-political sense, the word liberal dates to the 14th century in English, with various meanings available – to wit, someone who is free in giving or generous, someone of a certain occupation, education or field of study (e.g., the liberal arts), etc.

[iii] The Treccani and the RAE, respectively, if you want to know.

[iv] See this discussion between a European and an American scholar for a further example, albeit in another context.

[v] A look at more established encyclopaedias (the Britannica, the Treccani, etc.) paints much the same picture.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.