by Mike Bendzela

It sometimes wrenches my own credulity when I think about it: The sweeping and violent imaginings of a Southern fake war adventurer, college as well as high school drop-out, and binge-drinking, adulterous sometime-screenwriter, whose pissed-off wife once bonked him on the head with a croquet mallet, became encysted, like a wasp’s gall, in the head of a naive, Midwestern closet case as he was meandering through college for five years trying to find a major that suited him. While admittedly selective, this description is true, which I think is hilarious but which my partner, upon my reading it to him, thinks is “not very positive.” William Faulkner could never be accused of being positive, and that was his strength: He could stare down human malignity like no other, all the while maintaining a detached, unblinking vision that refused to look away. As one of his characters, Cash Bundren, says: “It’s like there was a fellow in every man that’s done a-past the sanity or insanity, that watches the sane and the insane doings of that man with the same horror and the same astonishment.”

I had to burrow my way through several sciences (geology, botany), arts (painting and drawing), performing listlessly in all of them, before finding myself in the early 1980s in a course called Early Twentieth-Century American Fiction, taught by a tall, passionate Black woman named Anna Robinson (about whom I can find nothing on the Internet), and thinking I should change my major to American Lit. She promptly shoved the novel As I Lay Dying under our noses. I bridled. What the hell is this? I fumed. Why do we get one character’s point of view on one page and another’s on the next? I seethed. Who are these people? Why do they talk so funny? Why do they think so funny? They do not even agree about what is going on. Over forty years later, I can still hear Professor Robinson quoting Addie Bundren’s line about her listless marriage from the middle of the novel — after she has died! — “And so I took Anse.” The time sequence is out of joint. Characters narrate scenes in which they are not present. What the hell, indeed. It was like hearing Thelonious Monk for the first time.

In spite of my heaving the gorge over Faulkner’s novel, I still enjoyed the course. Professor Robinson tilted our readings toward Southern short story writers and novelists — Flannery O’Connor, Zora Neale Hurston, Ernest J. Gaines — along with the likes of Philip Roth, Joyce Carol Oates, and Saul Bellow. I granted that Faulkner (whom I chose not to write about on our exam) at least wrote a terrifically creepy short story, “A Rose for Emily,” which, like the first egg laid by the gall wasp, triggered the cyst to grow in my imagination. It was only the following summer, after reading a few more transfixing short tales (“That Evening Sun,” “Barn Burning”) that I stared at the black block of Vintage Faulkner novels lining my bedroom bookshelf and decided I had to get through As I Lay Dying at least once.

*

After all these decades, I’ve begun looking back at some of Faulkner’s other works that captivated me as a young student. Some of them hold up, others not. In spite of my dense annotations on the copy, the brick-sized story “The Bear” no longer entrances me as it used to — it’s overly long and parts of it are impenetrable to me now — but it contains a scene with an indelible image that I have revisited in my imagination over the decades for its persistent numinousness. The mythic bear in this adventure tale to beat all adventure tales is Old Ben, a beast “with one trap-ruined foot” who is part Grendel, part Moby Dick. The human quest to kill Old Ben has been generational, going back even to the indigenous Chickasaw. In a sort of rite of passage, the young hunting apprentice, Ike McCaslin, allows himself to become lost in the forest north of the Tallahatchie River, in order to test the woodsman skills taught to him by his guide, Sam Fathers. He “relinquishes” his watch and compass by hanging them on a tree and “entered [the forest]” . . . “completely.” When he cannot find his way back to his equipment, he does as Fathers instructed him and finds a log on which to sit and think:

[. . .] seeing as he sat down on the log the crooked print, the warped indentation in the wet ground which while he looked at it continued to fill with water until it was level full and the water began to overflow and the sides of the print began to dissolve away.

That’s how close Ike was to seeing Old Ben. Readers come away from the tale with a permanent impression of having stood with Ike right next to the wild heart of the Southern wilderness.

Other stories I’ve looked back into: “A Rose for Emily,” which still reads like the classic it is, so cleverly structured to prepare for its surprise ending that it seems almost too good; “Spotted Horses,” both versions, first the chapter from the novel The Hamlet narrated in third person, then the short story version narrated by the sewing machine agent, Ratliff, which is a tighter, more superior over-the-top comic tale for the use of Ratliff’s native Mississippian voice. He tells of swindler Flem Snopes and his Texas sidekick, who come via wagon into town, intent on auctioning off a bunch of “gaudy” horses to the locals:

[T]ied to the tail-gate of the wagon was about two dozen of them Texas ponies, hitched to one another with barbed wire. They was colored like parrots and they was as quiet as doves, and ere a one of them would kill you quick as a rattlesnake. Nere a one of them had two eyes the same color, and nere a one of them had even seen a bridle, I reckon. . . .

The horror story “That Evening Sun” is still acutely shocking, containing scenes of unspeakable violence, misogyny, and racism. The protagonist, Nancy, is a Black laundress “after the old custom” for the Compson family (which family’s disintegration is described in The Sound and the Fury). Nancy knows she is going to die at the hand of her jealous husband, Jesus, who is enraged that “white man can come in my house” (in this case “a deacon in the Baptist church”) and impregnate his wife but there is nothing he can do about it. Nancy is terrified of Jesus lurking in the dark and never wants to leave the Compson house. She says to the father, Jason Sr., who Nancy insists walk her home in the dark with the Compson children along as company:

“I can feel him [Jesus]. I can feel him now, in this lane. He hearing us talk, every word, hid somewhere, waiting. I ain’t seen him, and I ain’t going to see him again but once more, with that razor in his mouth. That razor on that string down his back, inside his shirt. And then I ain’t going to be even surprised.”

What gives the story its horrifying impact is that it’s distilled through a naive narrator, Quentin Compson (who will later go on to kill himself), only ten years old at the time of the events in the story. Quentin is thinking back to the incident and regresses into his younger self as he tells the tale. He recalls Nancy’s unsettling behavior — she moans and groans for seemingly no reason; she is terrified of the ditch in front of the house; she cannot even hold still a cup of coffee — and juxtaposes this with the patter of his clueless siblings, Caddie and Jason Jr.:

“Nancy’s scaired of the dark,” Jason said.

“So are you,” Caddy said.

“I’m not,” Jason said.

“Scairdy cat,” Caddy said.

“I’m not,” Jason said.

Nancy’s murder is a foregone conclusion, as she reports to the family that she “got the sign”: She found on her table one night “a hog bone, with blood meat still on it,” a symbol of imminent death in Black Southern folklore, placed there, presumably, by the estranged husband. Her slaughter at the hands of Jesus is effectively left out of Quentin’s narrative.

*

In reviewing As I Lay Dying for the current essay — my favorite novel of all time, the novel that put a fine and fitting end to my ambitions of writing novels — it swallowed me up again, whole, right from the first scene when the oldest son, Cash, is building a coffin directly outside his dying mother’s bedroom window. I suddenly remembered that one key for my apprehending Faulkner’s imaginative landscape was seeing the novel set in the Kentucky I visited in my childhood: It has the same rugged topography; dangerous, flood-prone cricks deep inside rambling hollers; and thick, steaming woodlands. I recall that when I took the book off my shelf after taking Professor Robinson’s course, the narrative that I had found off-putting during the class suddenly struck me like a fever-dream set in my aunt’s family’s rural homestead on the Appalachian Plateau. None of the characters bears any resemblance to any of my relatives, though; it is my memory of the landscape of northeastern Kentucky that carries the story into my deepest mind. This is ironic given that northeastern Kentucky is further away from the novel’s setting in northwestern Mississippi than my childhood home in northern Ohio is from northeastern Kentucky! Almost twice as far, in fact. Still, as “the South,” it occupies the same mental region of my imagination.

There are fifteen different narrative streams in this short novel, placed out of order, out of time, but roughly following the sequence of events around the Bundren family’s journey with their mother’s rapidly decaying corpse over the back roads of northern Mississippi to grant her life-long wish to be buried with her relatives in faraway Jefferson, part of Faulkner’s imaginary “postage stamp of native soil,” Yoknapatawpha County. This wish of hers may be read as Addie’s final act of revenge against her shiftless husband, Anse.

Continually tracked by buzzards, weathering an epic, destructive flood (which I now visualize in terms of the recent horror of Hurricane Helene in North Carolina), narrowly escaping a sudden arson fire, the Bundrens scandalize their neighbors while repeatedly inflicting deep harm on each other during their journey. A few neighbors and the family doctor form scathing, critical counter-narratives to the self-serving accounts told by husband Anse and other members of the Bundren family — including the dead Addie Bundren herself over halfway through the trip.

The novel’s multiple stream-of-consciousness narrators issue discourse that can only be described as delirious at times, even delusional. In a remarkable C-SPAN interview conducted in 2001, Brian Lamb asked historian Shelby Foote, who had met Faulkner several times, if he knew if Faulkner ever drank while he was writing. Foote responded, “I do not believe so. . . . I’m a writer myself. You can’t write while you’re drunk,” just as one cannot drive or do about anything else while drunk. Faulkner had to have been sober to have written something as novel As I Lay Dying, but first time readers may be forgiven for thinking otherwise.

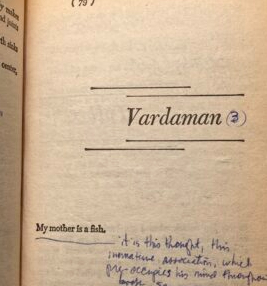

The primary voice is that of the second eldest son, the deeply disturbed Darl, whose consciousness is more penetrating and articulate than that of the rest of the family, but whom Faulkner himself described as “mad from the first.” He narrates scenes he was not there to witness — including his mother Addie’s death back at home while he and his younger brother Jewel are out with a broken-down wagonload of lumber in the rain after trying to earn a few bucks before they were to head to Jefferson. He is a visionary of sorts, communicating non-verbally with his teenage sister, Dewey Dell (!) who he intuits, correctly, is pregnant with an absentee farm hand’s child, and engaging in cryptic, symbolic conversations with his child brother, the severely traumatized Vardaman.

Hallucinatory scenes like the following, an interior monologue/stream-of-consciousness selection from one of Dewey Dell’s chapters, could not possibly issue from a mind addled by alcohol but from an artist carefully limning what would normally be inaccessible to us, the private experience of another human being. The Bundren family are in their mule-drawn, ramshackle wagon with their mother’s coffin, passing the sign post to their last hope for a rational end to their journey, the settlement of New Hope (ha), with a nearby cemetery where other Bundrens are buried. Darl is watching Dewey Dell’s reaction as they pass the sign, as he has divined that when the family gets to faraway Jefferson, ostensibly to bury Addie there as she has wished, Dewey Dell will be seeking out the nearest city doctor to give her an abortion:

The land runs out of Darl’s eyes; they swim to pin-points. They begin at my feet and arise along my body to my face, and then my dress is gone: I sit naked on the seat above the unhurrying mules, above the travail.

He sees right through her, as it were, and her sexual guilt is revealed: Then she intuits his words in an italicized passage in which he taunts her with the prospect of asking their father to divert their journey from Jefferson toward New Hope, thus dashing her hopes for an abortion:

Suppose I tell him to turn. He will do what I say. Dont you know he will do what I say?

She then recalls awaking from a bizarre dream involving young brother Vardaman, who had caught a huge fish a few days before:

Once I waked with a black void rushing under me. I could not see. I could see Vardaman rise and go to the window and strike the knife into the fish, the blood gushing, hissing like steam but I could not see.

This gives way once more to Darl’s voice speaking inside her:

He’ll do as I say. He always does. I can persuade him to anything. You know I can. Suppose I say Turn here.

Back to her consciousness of her helplessness; and back to Darl’s voice:

That was when I died that time. Suppose I do. We’ll go to New Hope. We wont have to go to town.

After a purposeful blank in the text indicating a suspension in her thought, the paragraph ends with a violent fantasy of her stopping Darl’s intrusion into her consciousness:

I rose and took the knife from the streaming fish still hissing and I killed Darl.

That’s just one paragraph in a 250-page novel full of such paragraphs — not drunken rantings but rich, evocative imaginings of a family deeply in conflict with themselves and their reputed mission of granting their mother’s last wish: It turns out they’re all like Dewey Dell; they each have unspoken ulterior motives for getting to town. Only crazy-ass Darl sees through the ruse and would do anything to terminate their misguided journey — including burning down a neighborly man’s barn, with his mother’s stinking coffin still inside.

Coda

My exit from the Faulknerian world was an experience bordering on exorcism. Having spent a summer plowing through several of the novels, I toyed with the idea of becoming a William Faulkner scholar once I had entered graduate school a year later. I finished up my English degree with an emphasis on American Literature and headed via Greyhound bus to Upstate New York in the fall of 1983, loaded with just a backpack and a few boxes of books and kitchenware.

It would happen that this university had an in-house Faulkner scholar. Even more happily, he was teaching a course in William Faulkner Studies that very Fall Semester! So, I enrolled and sat in a room with perhaps a dozen other students who looked forward to examining a handful of short stories before heading on to the giant novels, The Sound and the Fury, Absalom, Absalom!, and Light in August. (As I Lay Dying was not on the syllabus, which was fine as I felt I already knew it inside and out.)

We began with a week of discussion of the short works “That Evening Sun” and “Dry September,” as this professor would focus on Faulkner’s unromanticized depiction of race relations in the US around the turn of the century. I wanted to shine, but this did not go well.

One of the first questions he asked us was about the significance of the title “That Evening Sun.” All these decades later, I can only paraphrase my wrong-if-clever answer: The central character Nancy’s nemesis is her husband, “Jesus”; and, as the professor had told us at the start, Flannery O’Connor once said, “The South is haunted by Christ.” Jesus certainly haunts Nancy in the tale. Perhaps, then, “Sun” is an ironic pun on “son,” Jesus being the Son of God; and the word “Evening” has abundant connotations of things ending, or about to end, such as the Old South and, more patently, Nancy’s life —

“NO!” The professor excoriated me, his voice booming in the little room. “What’s the matter with you? Are you one of these Deconstructionists? Do you think you can just say whatever pops into your head?”

(This is no paraphrase: I’m 99% sure in my mind that these were his exact words. I even made a mental note to look up what a “Deconstructionist” was.)

The answer to his query, as he told the rest of the room, is that the phrase comes (of course) from a very popular jazz song of the early twentieth century, “St. Louis Blues,” composed by African American composer W. C. Handy and sung by everyone from Bessie Smith to Bing Crosby. This was well known at the time of the story’s publication in 1931, after Faulkner had achieved his long-awaited fame with The Sound and the Fury.

I hate to see that evening sun go down

Yes, I hate to see that evening sun go down

‘Cause it makes me feel like I’m on my last go-round

Oh. Brilliant, Mr. William.

As I like to tell people, I went to graduate school to cure myself of graduate school. I would finish my two years, receive a master’s in English with a certificate in Creative Writing — no emphasis on William Faulkner though I still took courses in American Literature — and I would leave graduate studies, without ever looking back. I had certainly learned something: I learned that the PhD is primarily a social pursuit, not an intellectual one, where every discussion of every thing becomes a little boxing ring of contention; and that I was too solitary, too avoidant, to hack it. In short, I was not cut out for that shit.

In that first class during my first semester at SUNY, I heard a necessary message loud and clear: You do not belong here. This would turn out to be a good thing: Instead of heading out for a PhD in William Faulkner Studies somewhere else, I would go up to Maine for the summer, at a friend’s invitation, and I haven’t left.

Notes

Quotations from short stories, The Portable Faulkner, New York: Penguin Books, 1983.

Quotations from As I Lay Dying, New York: Vintage Books, 1964.

Video Interview, Shelby Foote on William Faulkner and the American South.

“St. Louis Blues.” (One hundred-year anniversary of the tune.)

Image

“My mother is a fish.” Photograph by the author.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.