by Mark Harvey

Most people don’t want to hear your sob stories, even if they pretend to be caring listeners. Even a good friend listening to your personal version of Orpheus and Eurydice—and making all the right noises—is probably focused on whether to put snow tires on their car Thursday or Friday.

Some of us turn to music to ease our mortal wounds and it’s a bit of a mystery as to why sad music is actually helpful. I turn to either classical or country music when I need to feel better about a loss or when things just won’t go my way. There is a vast distance between the ultra-cultured notes of, say, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and the decidedly baseborn lyrics of the country songsters I like. But lo and behold, each can have its healing powers, and a little of each might be the key to a good diet.

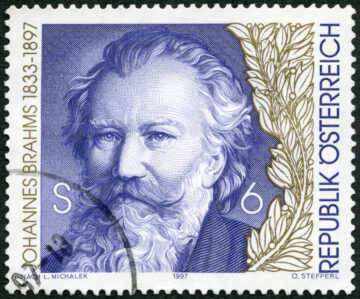

You can hear the grand wounds and the bending of the Weltgeist in classical music and it often involves losing a village or watching Napoleon fail at taking Russia. The great composers endeavor to capture tidal movements and tidal emotions. They have a whole orchestra with bizarre instruments such as glockenspiels and contrabassoons, to accompany the more common violins and pianos. To play in a great orchestra takes merely 15 years of daily practice from the age of four along with some otherworldly talent. So if you wake up feeling sad about the fall of democracy in Europe, by all means, reach for your Schubert or your Brahms. That’s what it takes to handle the bigger themes.

Country music is less ambitious and more concerned with things like, “Whose bed have your boots been under? And whose heart did you steal I wonder?”. But when you’re in the throes of a tawdry breakup, the clever, brassy lyrics of a Shania Twain or a Jamie Richards might offer the fast, powerful relief you need and can’t get from the refined classical music.

Good country music has the boomy-bassy-twangy sound made by simple instruments such as slide guitars, fiddles, and banjos. It can be plaintive and crooning but part of what makes it successful are clever, ironic lyrics. Read more »

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase. Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.

Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude. The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

Egypt

Egypt Germany

Germany