by Jeroen van Baar

In science, a good model describes one feature of the natural world well or solves one difficult problem. A great model, on the other hand, is often multipurpose. It serves as metaphor even where nobody expected it to.

Take one keyword of our current society: busy. In a 2018 Pew survey, 60% of Americans said they sometimes felt ‘too busy to enjoy life’. Between building a career, raising kids, and cleaning the house there seems to be barely enough time to cook or exercise or read or call your mother—even though we know those things are fun and good for you. On the other hand, there’s the adage that ‘if you want something done, ask a busy person’. Some busy people, it seems, can always fit in something small. While their time is scarce, their brains have room. How does that work?

A model from computer science can help us understand. Like us, computers have tasks to complete and to-dos to remember. And like us, they sometimes get overwhelmed. When sending an email over Gmail, there’s a 25 MB limit to the files you can attach. Try to send more, and the system calls in sick. A similar problem hits iPhone users after about two years, when they’ve taken enough puppy photos to exhaust the storage: the phone becomes achingly slow because it doesn’t have space to think.

The solution is compression. Before sending that large attachment, you turn it into a .ZIP archive and voilà, it has shrunk to 11 or 12 MB. This is amazing, if you think about it. Once the receiver unpacks the archive, exactly the same information is presented on their screen, but Gmail had to work a lot less hard for that. Read more »

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on. A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

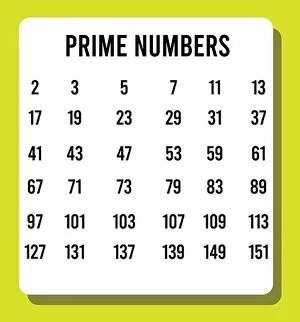

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.