by Mindy Clegg

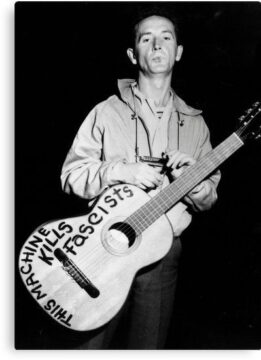

As I start this essay, early voting just began in my state of Georgia which is a critical swing state. Our secretary of state announced record turn out on the first day of early voting. By the time this is posted, I will have already voted, and perhaps that might be true of many Americans who frequent this website. Others might reject voting all together, as they might feel voting has become a pointless act. While true that voting is not the only act of democratic participation, in this case avoiding a worse-case scenario with a second Trump presidency who has a well-organized fascist movement behind him is critical for any positive change in the near future.

The roadmap for a second Trump term (Project 2025) ignores the many challenges we face as a society in favor of blaming the “other” and criminalizing dissent from Christian nationalism. Some try to argue that Harris, who seems to be pivoting to a centrist position on at least some issues, might not be much better. I am advocating embracing the lesser of two evils here and casting your vote for Harris. Let’s highlight some very good reasons why avoiding the nuclear option of fascism is always the right move.

One of the biggest sticking points for voters on the left (and rightly so) is the ongoing genocide in Gaza. Even for many staunch supporters of the Zionist project, the war is becoming harder to justify as it expands to Lebanon. Frustrated Arab American voters in Michigan have been angered by the lack of traction on ending the war by the Biden administration. As a result, some are claiming they’ll cast a vote for Trump, which seems wild, considering he refuses to acknowledge that Palestinians even exist. Others are leaning towards Stein, who espouses an anti-war stance. She did gain the endorsement of David Duke which she rejected, but one wonders why. Foreign policy is one area that the voters have little direct input on and historically, the majority of the public vote on domestic issues.

At times, wars and the threat of wars shaped our choices of president, such as during the Vietnam war. The choice is rarely stark, as US wielding power abroad is a bi-partisan issue. Many Democrats tend to be more hawkish at times, such as when Kennedy and Johnson expanded US involvement in the Vietnam war. Electing Nixon in 1968 proved to be a disaster, as his “plan” to get us out involved widening the US bombing campaign, trying to do so in secret, and setting neighboring Cambodia down the path of genocide. As bad as what’s happening right now in Gaza is (and it’s really, really bad), another term of Trump would mean the full liquidation of Gaza, an expansion into Lebanon, and even a major strike on the Iranian nuclear infrastructure. Read more »

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

When I was growing up, my mother and I would sometimes read or recite poetry to each other. Ours was not a poetic household, and my father would occasionally complain: “If poets have something to say, why don’t they just say it?” But we thought they did say it, albeit indirectly sometimes, and we continued with our Longfellow, a bit more quietly.

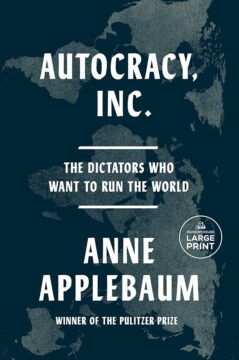

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Renowned and respected for her scholarship, her history of authorship of many books on dictatorship and her political experience, is it any wonder that Anne Applebaum’s new book Autocracy, Inc. The Dictators Who Want to Run the World has been so critically received; she is an expert on her subject. This slim volume provides us with an incisive exposition and analysis of how autocrats function in the world today, securing their own personal power and wealth, and in Applebaum’s view, posing a threat to democracies.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase.

Every time I read or watch anything about the election I hear some variant of the phrase “margin of error.” My mathematically attuned ears perk up, but usually it’s just a slightly pretentious way of saying the election is very close or else that it’s not very close. Schmargin of error might be a better name for metaphorical uses of the phrase. Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude.

Philosophical reflection on artificial intelligence (AI) has been a feature of the early days of cybernetics, with Alan Turing’s famous proposals on the notion of intelligence in the 1950s rearming old philosophical debates on the man-system or man-machine and the possibly mechanistic nature of cognition. However, AI raises questions on spheres of philosophy with the contemporary advent of connectionist artificial intelligence based on deep learning through artificial neural networks and the prodigies of generative foundation models. One of the most prominent examples is the philosophy of mind, which seeks to reflect on the benefits and limits of a computational approach to mind and consciousness. Other spheres of affected philosophies are ethics, which is confronted with original questions on agency and responsibility; political philosophy, which is obliged to think afresh about augmented action and algorithmic governance; the philosophy of language; the notion of aesthetics, which has to take an interest in artistic productions emerging from the latent spaces of AIs and where its traditional categories malfunction; and metaphysics, which has to think afresh about the supposed human exception or the question of finitude. The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate:

The opening credits of Affliction (1997) feature small, rectangular images that fill only half the screen. You wonder if something is wrong with the aspect ratio, or if the settings have been changed on your television. A succession of images is placed before the viewer: a farmhouse in a snowy field, a trailer with a police cruiser parked in front, the main street of a small, sleepy town, the schoolhouse, the town hall. The last image is a dark, rural road, with a mountain in the distance. Finally the edges of the image expand, fill the screen, and a voice begins to narrate: