by Terese Svoboda

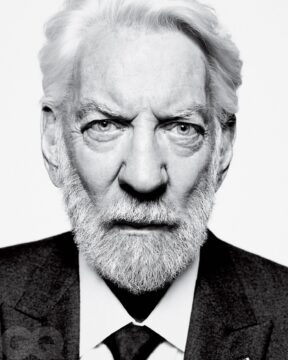

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

Donald Sutherland was a connoisseur of poetry. In the 80s I knew poetry-quoting doyennes from the glittering parties the Academy of American Poets threw as well as the Sudanese who recited their histories in song, but mostly I knew poets obsessed with competing with dead ones, with an eye toward their next book. Poets generally love poetry the way auto mechanics love cars. They don’t luxuriate in the front seat, or take long winding car trips through the Berkshires, they make sure the ignition catches and go on to the next one. Hearing Sutherland recite poetry you heard the Stanislavski method of poetry-recitation, an oral delivery straight from the mind as well as the mouth. Sutherland said he was manipulated by words, not as a ventriloquist but in the relationship between feeling and meaning. Likewise, after numerous tussles with directors Fellini and Preminger and Bertolucci – he even tried to get Robert Altman fired from M.A.S.H. – he decided he was merely the director’s vehicle. Poetry directed him.

I was newly blonde when I flew out to LA to convince him to be the host of Voices & Visions, a PBS series on American poetry that I was producing. The dye job wasn’t planned. The proto-reality TV show Real People had put up a Free Haircut sign in Soho and like any poet, I was attracted to the Free. All I had to do for the series was transform from a mousy brown thirty-year-old to a hot blonde punk in a red jumpsuit. No problem. I did a bit of strutting around on the set, and the program was ready for reruns. Unbeknownst to me, the executive director had been working his Canadian connection, the daughter of media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who knew Donald Sutherland and his proclivity toward poetry. Lunch had already been scheduled.

Sutherland had the anthology of baseball poetry we’d sent to him on his desk, baseball being his only other passion outside of acting. Veteran of nearly a hundred movies by that time, he’d recently stunned audiences with his performance in Ordinary People. Did I dare to mention my brush with Real People? All I remember of the business part of that first hour was the way he quoted Auden while skating his long fingers over his desk – not as an arpeggio of show-offy emphasis but unconsciously following the cadence. I was impressed. He needn’t have auditioned – if that’s what it was – because we were barely paying scale. He called in his manager, they thought something could be done, and he suggested lunch. After arguing with his manager about what car to take, he appeared outside his office at the wheel of a beautiful white convertible. The manager held the door for me, I got in – and we drove across the street. Ah, Hollywood. Read more »

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on.

In daily life we get along okay without what we call thinking. Indeed, most of the time we do our daily round without anything coming to our conscious mind – muscle memory and routines get us through the morning rituals of washing and making coffee. And when we do need to bring something to mind, to think about it, it’s often not felt to cause a lot of friction: where did I put my glasses? When does the train leave? and so on. A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

A good poem can do many things – be clever, edifying, provocative, or moving – but a truly great poem (which is to say a successful one), need only be concerned with one additional attribute, and that is an arresting turn of phrase. By that criterion, Ukrainian-American poet Ilya Kaminsky’s “We Lived Happily During the War,” originally published in Poetry in 2013 and later appearing in the 2019 collection Deaf Republic, is among the greatest English-language verses of this abbreviated century. Within the context of Deaf Republic, Kaminsky’s lyric takes part in a larger allegorical narrative, but that broader story in the collection aside, “We Lived Happily During the War” is arrestingly prescient of both the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Vladimir Putin’s brutal and ongoing assault on the broader country of Kaminsky’s birth since 2022, including bombardment of the poet’s home city of Odessa. Yet even stripped of this context, “We Lived Happily During the War” concerns itself with the general tumult of modern warfare, both its horror and prosaicness, its sanitation and its tragedy. More than just about Ukraine, or Syria, or Gaza, Kaminsky’s lyric is about us, those comfortable Western observers of warfare who have the privilege to be happy and content at the exact moment that others are being slaughtered.

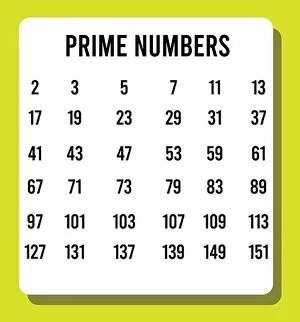

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are

Prime numbers are the atoms of arithmetic. Just as a water molecule can be broken into two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms, 12 can be broken into two 2s and a 3. Indeed, the defining feature of a prime number is that it cannot be factored into a nontrivial product of two smaller numbers. Two primes that are easy to remember are