by Tim Sommers

In “Calculating God,” Robert J. Sawyer’s first-contact novel, the aliens who arrive on Earth believe in the existence of God – without being particularly religious. Why?

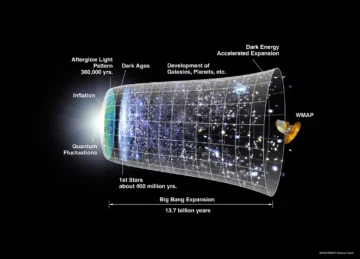

There are certain physical forces, they explain, that make life in our universe possible only if they are tuned to very specific values. Which they are. We are here, after all. But there’s no physical reason that the values need to be set the way they are. The aliens have concluded that someone, or something, set the values of these parameters at the beginning of the universe to insure that life would come into existence. That something they call God.

Here’s a much earlier, very different version of this argument. If you were hiking through the woods and you picked up a shiny object that turned out to be a small stone, it would probably not occur to you that it might have been made by someone. If it turned out to be a watch, however, you would immediately conclude that it had been intentionally created. So, is the universe more like a stone or a watch?

This argument from design was an especially powerful argument for the existence of God when very little was known about biology. The complexity of living things puts watches to shame. But then Darwin came along and used evolution to explain how such diversity, complexity, and apparent design could come about without a designer.

Just when the argument that the complexity of our world could only be explained by God seemed lost, a new, purely physical reason to think that the universe was designed appeared. The one the aliens embrace.

“A striking phenomenon uncovered by contemporary physics,” Kenneth Boyce and Philip Swenson write in their forthcoming paper “The Fine-Tuning Argument Against the Multiverse,” (Philosophy Quarterly) is that many of the fundamental constants of nature appear to have arbitrary values that happen to fall within extremely narrow life-permitting windows.” Read more »

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

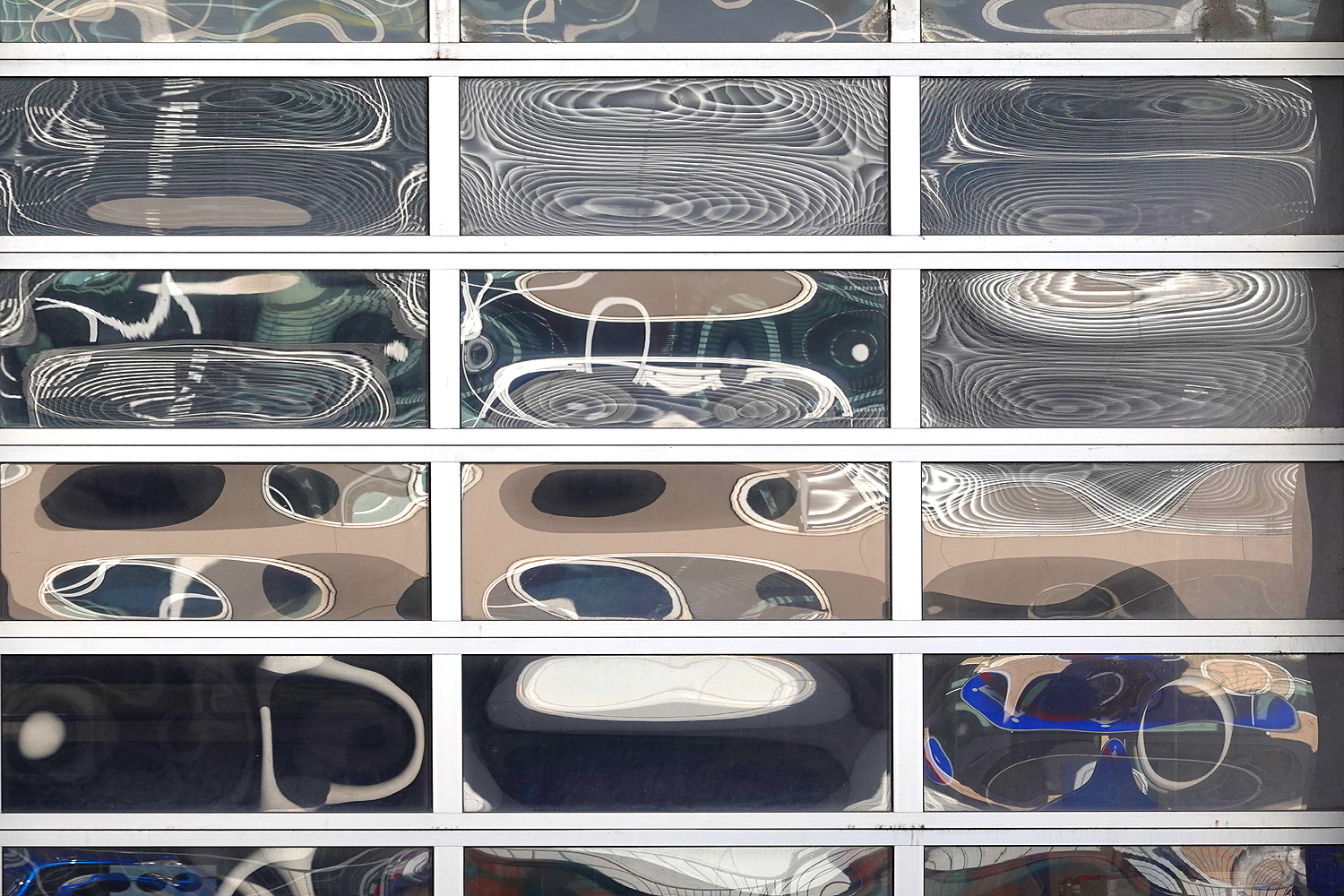

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.