by Derek Neal

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.

The movie opens with a scene in a taxi. A journalist is in the front seat while two armed military police officers sit in the back. The journalist explains to the driver that they are on their way to arrest a man who has been impersonating the filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. So far, so good. But what you don’t realize, unless you’re familiar with the film, is that most of these people are not actors. The journalist is a journalist and the police officers are police officers. So the director is going for realism, eschewing the use of professional actors in the manner of Bresson? Not quite. Makhmalbaf is a real Iranian director, and someone really did impersonate him—this is a true story, and many of the people in the film play themselves. The journalist is the real journalist who broke the story, which brought it to the attention of Kiarostami, leading him to make the movie. The officers are the real officers who arrested the impersonator. They are on their way to the real house of the family whom the impersonator conned, and the family as well as the impersonator play themselves, too. Everything in the film really happened—this is real life, close up. Or is it? Does filming something change it? Does a reenactment alter the original act? Can a copy replace the original? What is real and what is make believe, and can we cross back and forth between the two realms? Can one exist without the other? These are the questions the film presents to its viewers.

In the taxi on the way to the Ahankhah residence, where the impersonator will be arrested, the journalist asks the taxi driver if he knows the director Makhmalbaf, to which he responds, “I don’t have time for movies. I’m too busy with life!” Later, when Kiarostami tells the judge who will preside over the case that he would like to film the trial, the judge tells him, “I took a look at this case, and I don’t see anything worth filming.” The judge and the taxi driver insist on the difference between movies and real life, or more broadly, art and reality. Kiarostami seems to have something else in mind.

In the former scene, the scene in the taxi, the journalist Farazmand is playing himself whereas the taxi driver is portrayed by an actor (at least, he’s not listed as playing himself in the opening credits). This conversation, then, may not have really occurred, although the drive to the Ahankhah residence certainly did. Kiarostami has presumably inserted this dialogue to make the viewer question what is presented on the screen. Is it a movie, or is it life? The scene with the judge is also a reenactment, although this time all the characters play themselves. The judge is the real judge and Kiarostami, off camera, asks him questions. We are inclined to believe that this dialogue did take place, that the judge did question the worth of filming such a simple trial. But did he? There’s no way to know, and attempting to find out the truth only leads to more questions, as I discovered while researching the movie.

The film itself, contrary to the opinion of the taxi driver or the judge, proposes that something becomes worth filming when it is filmed; in other words, the act of representation itself makes its subject worthy of representation. No external explanation is needed other than the resulting piece of art, which, once it has been created, becomes a part of real life.

When the taxi arrives at the Ahankhah’s house, the camera remains outside with the taxi driver, leading to one of the most iconic scenes in cinema. Rather than show the arrest of the impersonator, Kiarostami’s camera remains focused on seemingly trivial details. The driver goes over to a pile of leaves and finds a few discarded roses on top. He picks them up, then takes a branch with leaves before putting it back. He moves around the pile and finds a pink rose to pair with the red ones he’s already found. A conscious decision is being made; art is being crafted from nature, and by a person who claims to be “too busy with life.” But if this is not life, what is it? While working, while waiting for his fare to return, he picks flowers and watches an airplane in the sky. The plot of the movie stops; time expands. The boundary between real life and movies begins to blur. Then the driver discovers an aerosol can on the ground. He nudges it the way a child might, curious to see how long it will roll down the road. By my count, it rolls for 35 seconds. Surely none of this “really” happened—what really happened is going on off screen, unknown to the viewer. So why film the flowers and the can? Why hold a shot for 35 seconds? Because filming something makes it worth filming. In taking an interest in the aerosol can, new discoveries are made. As the can rolls downhill, this is visualized as the can moving from the bottom of the screen to the top of the screen. The camera has to pan upward to keep the can in frame, and in doing so, leaves the close image of the road to take in buildings in the distance, then the sky above. Part of what makes the shot so remarkable is not only the length, but also the passage from closed to open, and the sense of release that one experiences as the camera takes in more and more depth. The message the film is telling the viewer is expressed in cinematic language that cannot be translated to words—pure cinema.

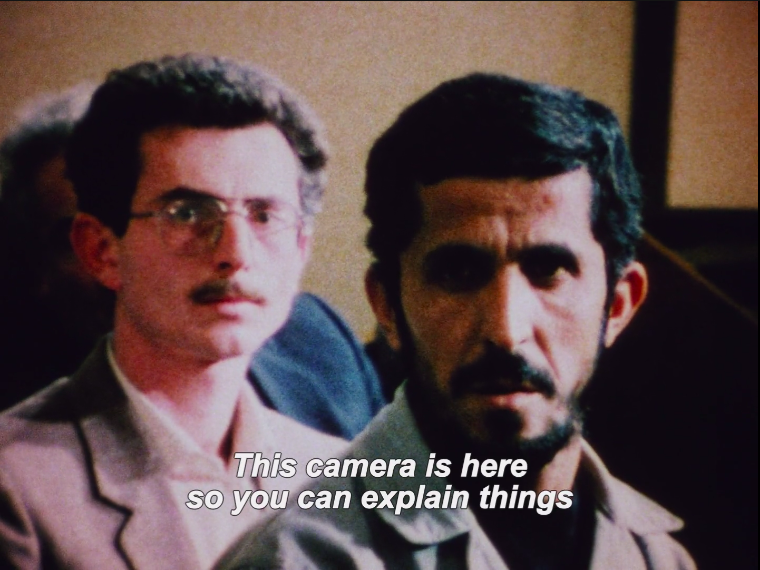

The trial, which forms the centerpiece of the film, begins with a clapperboard that says, “Scene 1, Shot 1, Law Courts, Nov. 9” and the typical clap indicating that filming has started. The impersonator, named Sabzian, enters the courtroom in handcuffs. The quality of the film itself is grainy 16 mm, different from the clean images shot on 35 mm for the reenactment scenes, and the impression one has is that this is documentary footage. This is the real trial. But what if the use of these devices—the clapperboard, the 16 mm film, the boom microphone that enters the shot at one point—are more artifice, simply devices used to present an image of authenticity? When I viewed the film, I assumed this was the real trial. Yet by filming the trial, Kiarostami permanently alters it. Before the judge can talk, Kiarostami speaks off screen, telling Sabzian, “This camera is here so you can explain things,” and then, “If there’s anything needing special attention or that you find questionable, explain it to this camera.” Then the trial begins with the judge invoking Allah, although, in a sense, it has already begun. After some minutes of testimony from Sabzian and the Ahankhah family, Kiarostami interjects again. “With the court’s permission,” he says, “explain why you [Sabzian] chose to pass yourself off as Makhmalbaf, because so far I don’t think you really have.”

Up to this point, the trial has not explained anything. It is unclear why Sabzian has impersonated a director, or if he has any ulterior motives, such as gaining access to the Ahankhah residence to rob them. The trial, which is supposed to be a way for the involved parties to discover the truth and come to some sort of conclusion, cannot interpret Sabzian’s act.

Kiarostami, however, seems to sense that Sabzian’s motivations are artistic, which is why he attempts to turn the narrative of the trial in a new direction. In his question, “Explain why you chose to pass yourself off as Makhmalbaf,” I hear something else: Explain why you chose to pass yourself off as a director. Explain why you chose to pass yourself off as an artist. Explain why you chose to be an artist.

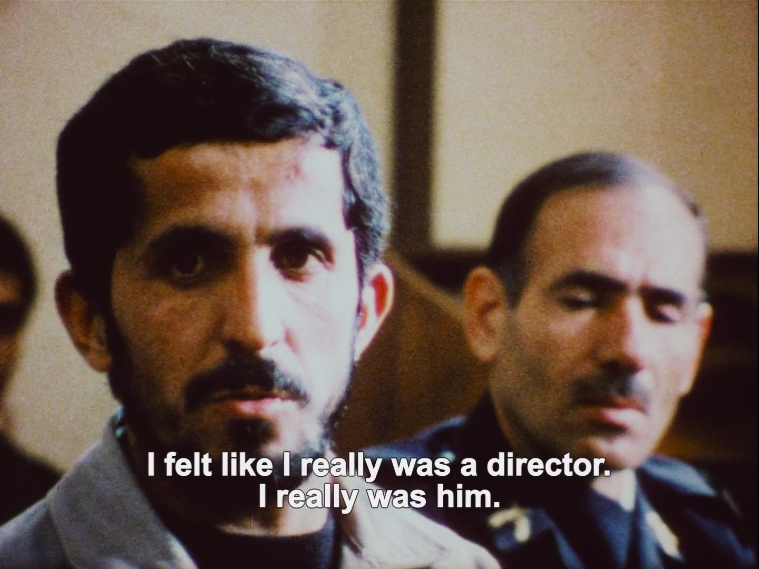

Sabzian explains: “Being Makhmalbaf was very hard for me,” by which he seems to mean not impersonating Makhmalbaf by copying his mannerisms or appearance, but impersonating a director—an artist. How does one become an artist? Sabzian explains how he began to succeed in his impersonation:

Because of my passion for cinema, and above all because they respected me and supported me morally, I really got into the part. It encouraged me to play the role better to where I even felt I was a director. I was really him. I felt like I really was a director. I really was him.

If one believes oneself to be a director, and others validate this belief, then one is a director. Sabzian continues: “When they respected me and believed I really was a director, their trust gave me confidence…When he lent me money, I realized he was convinced I was a director.” Sabzian doesn’t seem to have a plan, yet things proceed little by little, and one thing leads to another. He sees the possibility for making a film: “He [the Ahankhah son] was so keen to be in a film that I wished I had money to make a film…” Sabzian proposes that members of the family star in “Makhmalbaf’s” next movie, which he calls The House of the Spider; he even inspects rooms of their house to explain how it will be filmed and asks them to cut down a tree in their yard to improve the view of the house. When the judge asks if Sabzian planned on asking the Ahankhah’s to fund the movie, he says “It was my intention that if they put up money—if he’d said, ‘I’ll put up money for your film,’ I’d have done it—but I wouldn’t have let things get that far.” Sabzian contradicts himself here—would he have made the movie or not? To make the movie he would have needed to believe that he could make the movie, and perhaps, in the courtroom with the ruse up, he loses that belief.

While watching this scene, I thought back to the bell scene in Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, another movie about the struggle to be an artist. In one chapter of the story, set in 15th century Russia, a few emissaries go in search of another man who is known as a bellmaker. They don’t find the man—he’s dead, along with the rest of town due to plague—but they find his surviving son. As the men prepare to leave, the son stops them, sensing an opportunity, and tells them that they “don’t know the bell-making secret” and therefore won’t succeed in the casting of the bell. But the son does know the secret, because his father passed it on to him, or so he says. The men are persuaded to bring the boy along and put him in charge of the bell-making operation, a huge endeavor with hundreds of men working over multiple months. This will culminate in the tolling of the bell, an event for which the Russian Prince is present as well as a few Italian noblemen. If the bell doesn’t ring, the boy will be executed. The bell rings. The boy has done it, his secret allowing him to succeed. But then Andrei, the hero of the film who has been watching from afar, mired in his own artistic crisis, finds the boy crying. Andrei consoles him. The boy confesses: “My father, that old snake, didn’t pass on the secret. He died without telling me. He took it to the grave.” There is no secret to artmaking, it seems, besides faith in one’s own creation, which makes art possible.

Sabzian appears, at times, to have this faith. His monologues in court are captivating, and he goes on for multiple minutes without stopping, explaining his love of cinema:

Whenever I feel depressed or overwhelmed, I feel the urge to shout to the world the anguish of my soul, the torments I’ve experienced, all my sorrows—but no one wants to hear about them. Then a good man [Makhmalbaf] comes along who portrays all my suffering in his films, and I can go see them over and over again. They show the evil faces of those who play with the lives of others, the rich who pay no attention to the simple material needs of the poor. That’s why I felt compelled to take solace in that screenplay [The Cyclist by Makhmalbaf]. I read it, and it brings calm to my heart. It says the things I wish I could express…

While watching Close-Up, the camera zoomed in on Sabzian’s face, I was greatly moved by his articulation of what art meant to him. I wanted the family to pardon him, to understand that his act was not done out of malice, but out of love for art. I identified completely with Sabzian. Imagine my surprise, then, when I discovered that this supposed “real” trial might not have been real at all. I knew that Kiarostami had altered the trial by filming it and that he’d moved the date forward by two months to accommodate his own filming schedule, but I didn’t know that he’d also shot footage with Sabzian to supplement the real trial, apparently nine hours’ worth. I didn’t know that he’d scripted some of Sabzian’s lines, lines that I thought had been a spontaneous outpouring from Sabzian’s tortured soul. I didn’t know he’d interspersed this footage with shots of the judge to make it look like one continuous scene. I went back and re-watched the trial scene and noticed how at times members of the Akenkhah family were visible behind Sabzian, but at other times the camera was zoomed in so closely that they couldn’t be seen. They weren’t there. At the beginning of the trial, when Kiarostami tells Sabzian, “this camera is here so you can explain things,” he’s referring to a camera with a close-up lens, which is one of two cameras that will be used to film the trial. The other camera has a wide-angle lens and is used to film the courtroom. The close-up shot, then, is presented as a way to get as close to the truth as possible. But what if, in coming so close, perspective is lost? The close up, the symbol of authenticity—of real, raw life—can also be the most deceptive shot.

At the end of the trial, Kiarostami asks Sabzian if he would make a better actor than a director, to which Sabzian responds:

I think I could express all the bad experiences I’ve had, all the deprivation I’ve felt with every fiber of my being. I think I could get these feelings across through my acting.

Kiarostami asks him if he’s acting right now, to which Sabzian says:

I’m speaking of my suffering. I’m not acting. I’m speaking from the heart. This isn’t acting. For me, art is the experience of what you’ve felt inside. If one could cultivate that experience, it’s like when Tolstoy says, that art is the inner experience cultivated by the artist and conveyed to his audience.

Knowing that Kiarostami may have scripted these lines, and that neither the judge nor the Ahankhah family may be present in the courtroom, would it be correct to say that Sabzian is acting? Would it be correct to say that this is “not real”? This is the wrong question. Sabzian has made these lines his own, the part he is playing is his own, as Kiarostami suggests to him later. Kiarostami, himself, is also speaking through Sabzian, expressing his understanding of art, yet this is only made possible by turning Sabzian into a “character.” If art is “the experience of what you’ve felt inside” and that is “not acting,” then there is no difference between art and real life, and the dichotomy between the two is revealed to be a false one. If one has enough conviction, enough faith, what is false can be made real.

At one point in the trial, one of the Ahankhah sons relates a story Sabzian told him while they were riding on a motorcycle:

As we rode along, he spoke about filmmaking as if he was Makhmalbaf…Then he told me he’d just gotten an interesting idea for a film about two people on a motorcycle. One loses his wallet and has no other money on him…Two men ride along on a motorcycle for half an hour because one has lost his money, the other lends him some, and they become good friends.

Close-Up ends with Sabzian’s release from prison. The real Makhmalbaf is there to meet him, on a motorcycle. Kiarostami is filming. One is tempted to ask: is this the real shot? Did they really send Makhmalbaf to surprise Sabzian? Did he know about it? But we can’t ask these questions—they don’t matter. When Sabzian sees Makhmalbaf, he starts crying and collapses into his arms. Is he act—? They get on a motorcycle, and ride off, then stop for to pick up flowers to deliver to the Ahankhah’s, but Sabzian doesn’t have any money. Makhmalbaf lends him some. Perhaps they will become good friends.

They get back on the motorcycle and the soundtrack from Kiarostami’s previous film The Traveler begins to play.

Earlier in the film, during the trial, Sabzian said this:

I admire him [Makhmalbaf] for the films he’s given society and the suffering he portrays in his films. He spoke for me and depicted my suffering, especially in Marriage of the Blessed, just as Mr. Kiarostami does, especially in The Traveler. You could say I’m exactly like that traveler.

In Close-Up, Sabzian’s film has become a reality at the same time he has become a character in his own life.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.