by Katalin Balog

The mind-body problem in its current form – an inquiry into how the mind fits into the physical universe – was formulated by René Descartes in the 17th century. In his Meditations, a thin volume of philosophy that had a monumental effect on all later Western philosophy, he famously argued that it is possible to conceive of a mind without extension – a disembodied soul – and a body without thought – a mindless zombie. And since whatever can be clearly and distinctly conceived, can be brought about by God, it is possible for there to be a mind without body and a body without mind. He concludes, based on observations about our concept of mind and body, that they are really distinct. His position is called dualism, which is the view that the world has fundamental ingredients that are not physical. Of course, dualism was not original to Descartes; from Plato to the Doctors of the Church and ordinary folks, most people up until the Enlightenment have advocated it. But his way of arriving at it – examining what he can “clearly and distinctly” conceive – has set the template for all subsequent discussions. Nota bene, he had more empirically based arguments as well; for example, he thought nothing physical could produce something so open ended and creative as human speech. He would have been very surprised by ChatGPT.

According to Descartes, the mind, or soul, is an exalted thing: it is non-spatial, immaterial, immortal, and entirely free in its volition. He also thought – reasonably enough – that it interacts with the body, an extended, spatially located thing. In Descartes’ view, there are sui generis mental causes; purely physical causes cannot explain actions. Descartes held that only the quantity of motion is strictly physically determined, not its directionality. In Leibniz’s telling of the story in The Monadology, Descartes believed that the mind nudges moving particles of matter in the pineal gland, causing them to swerve without losing speed, like the car going around the corner. He had a real, substantive disagreement with his contemporary Hobbes, a materialist who thought that there were only physical causes.

Developments in science have had an enormous impact on this debate. The gist is that advances in the physical and biological sciences ultimately ruled out Descartes’s idea of the mind as a sui generis force – though not necessarily other forms of dualism which we will talk about shortly. Not only is it hard to comprehend Descartes’ idea that a non-material mind can move a material body, but such sui generis non-physical causes are ruled out by what we know about natural processes. Read more »

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

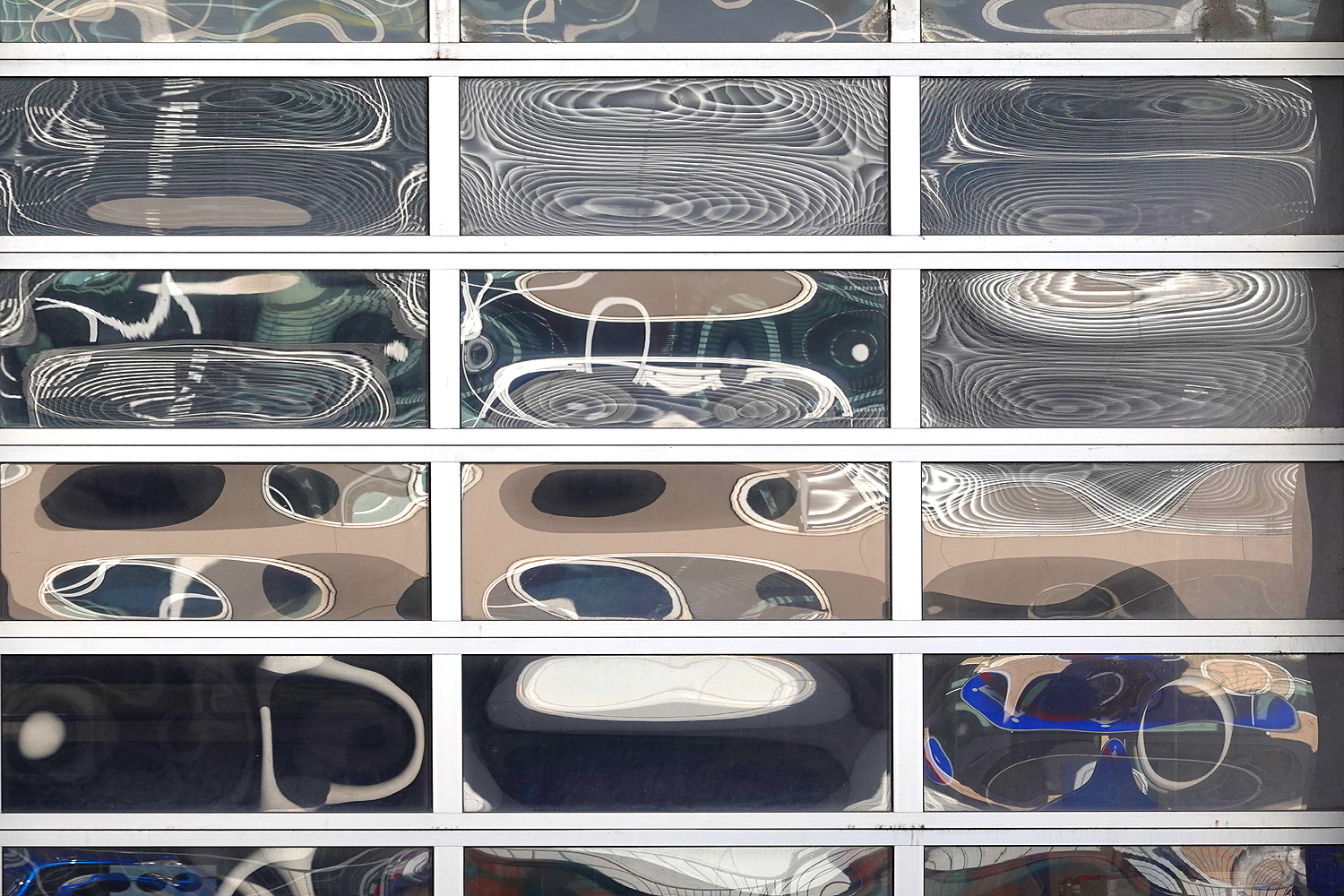

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Monica Rezman. After Dark. 2023. (“this is what it’s like to live in the tropics”)

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.

Close-Up, a 1990 Iranian film directed by Abbas Kiarostami, is one of the rare films where the viewing experience is enhanced by knowing certain details beforehand.