by Christopher Hall

“In 2025, during an event to celebrate the inauguration of Donald Trump for his second term, the richest man in the world gave a Nazi salute to the crowd.” This is a sentence which, circa 2005, would have made for a rather overblown introduction for a YA dystopian novel. But here we are, and it did happen. It did happen – right? No, calling this a Nazi salute was leftist cancel culture in action. No, Elon is just very socially awkward and/or autistic. No, even the Anti-Defamation League says it wasn’t a Nazi salute. In many corners of the media, the message was simple: don’t believe your lying eyes.

What is inescapable is the sense of the ludicrous – you either think it’s ludicrous that we’re debating at all what was clearly a fascist gesture, or that there are people who think so, because it clearly wasn’t. The interpretational gambits being played here are both nettlesome and exhausting. And it isn’t solved by simply dismissing Musk as a troll. The strange loop of trolling, where we’re moving forward but we somehow end up at the beginning, usually involves the question of intention, always daring you to think both that he really means it and that it’s all a joke. And so maybe Musk’s gesture was innocent and maybe it wasn’t – but that’s all part of the troll. How can you take such a thing so seriously? (How can you not?) An arm raised at roughly a 45 degree angle – that’s what upsets you? (It’s literal Nazism, so of course it does!) But his hand was raised at a slightly higher angle – isn’t that just a wave? (Oh, stop bothering me and go read your Trump Bible.) It may be that Kekistan is long past its expiration date (the half-life of memes being pretty short), but the spirit remains intact and present. Trolling is a language game, and you lose if you react to it at all.

Trolling is also, as is frequently said, an art, and as perverse as it may sound, I want to look for a moment at The Gesture as a work of performance art. Read more »

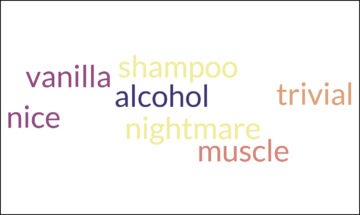

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature? As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

One day I went to

One day I went to  I gazed at the pages,

I gazed at the pages,

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

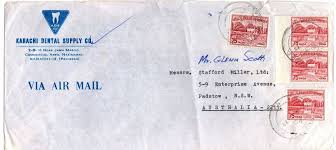

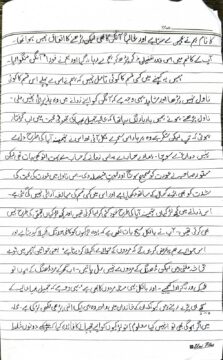

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an