by Priya Malhotra

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?

What do an intoxicating drink and an ancient beauty ritual have in common? How did a word once linked to Roman roads become synonymous with insignificance? And what strange connection exists between human strength and a tiny, scurrying creature?

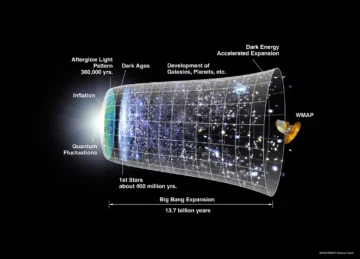

Language is a traveler. Words cross borders, crisscross centuries, and sometimes transform so completely that their meaning is completely altered. A term that once conveyed insult might, centuries later, become a compliment. A spice that once evoked luxury may later come to symbolize the ordinary. A simple verb in one language may be borrowed and reshaped into something spectacular in another.

The English language, restless and ever-expanding, is a patchwork of borrowed words, forgotten histories, and surprising transformations. While the English language’s primary roots lie in Old English, Old Norse, Latin, and French, it has also incorporated words from languages such as Arabic, Hindi, Dutch, Italian, and Japanese. Some words have arrived quietly, slipping into common speech without much notice. Others are shaped by conquest, trade, or scientific discovery. But every word has a journey—a story hidden beneath its surface, waiting to be uncovered.

Here are seven words whose unexpected and dramatic voyages through time and place remind us that language is not something static – it’s always moving and always changing.

- Nice

For a word that now suggests something bland, colorless, and ineffectual, nice has had quite the rip-roaring journey. It started off as an insult. Originating from the Latin word nescius meaning “ignorant” or “unaware,” it entered Old French as nice, as in “careless” or “clumsy.” By the late 13th century, Middle English adopted nice to describe someone as “foolish” or “senseless.”

Over the subsequent centuries, nice experienced a series of dramatic shifts in meaning. In the 14th century, it conveyed the sense of being “wanton” or “lascivious,” a far cry from its modern use. By the 15th century, it had transformed again, then used to describe someone who was “fastidious” or “fussy.” It was only in the late 18th century that nice emerged as the polite and pleasant word we recognize today. Read more »

As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

As a lawyer I know too well that lawyers are infamous for looking for the dark lining in a silver cloud. That outlook goes with the territory of trying to look for legal pitfalls and hidden trap doors. That’s part of the job of what lawyers do—trying to protect their clients from legal liability and unexpected detours and disasters that could have been avoided by careful drafting or strategizing. That doesn’t mean lawyers are pessimists but sometimes it is taken that way.

One day I went to

One day I went to  I gazed at the pages,

I gazed at the pages,

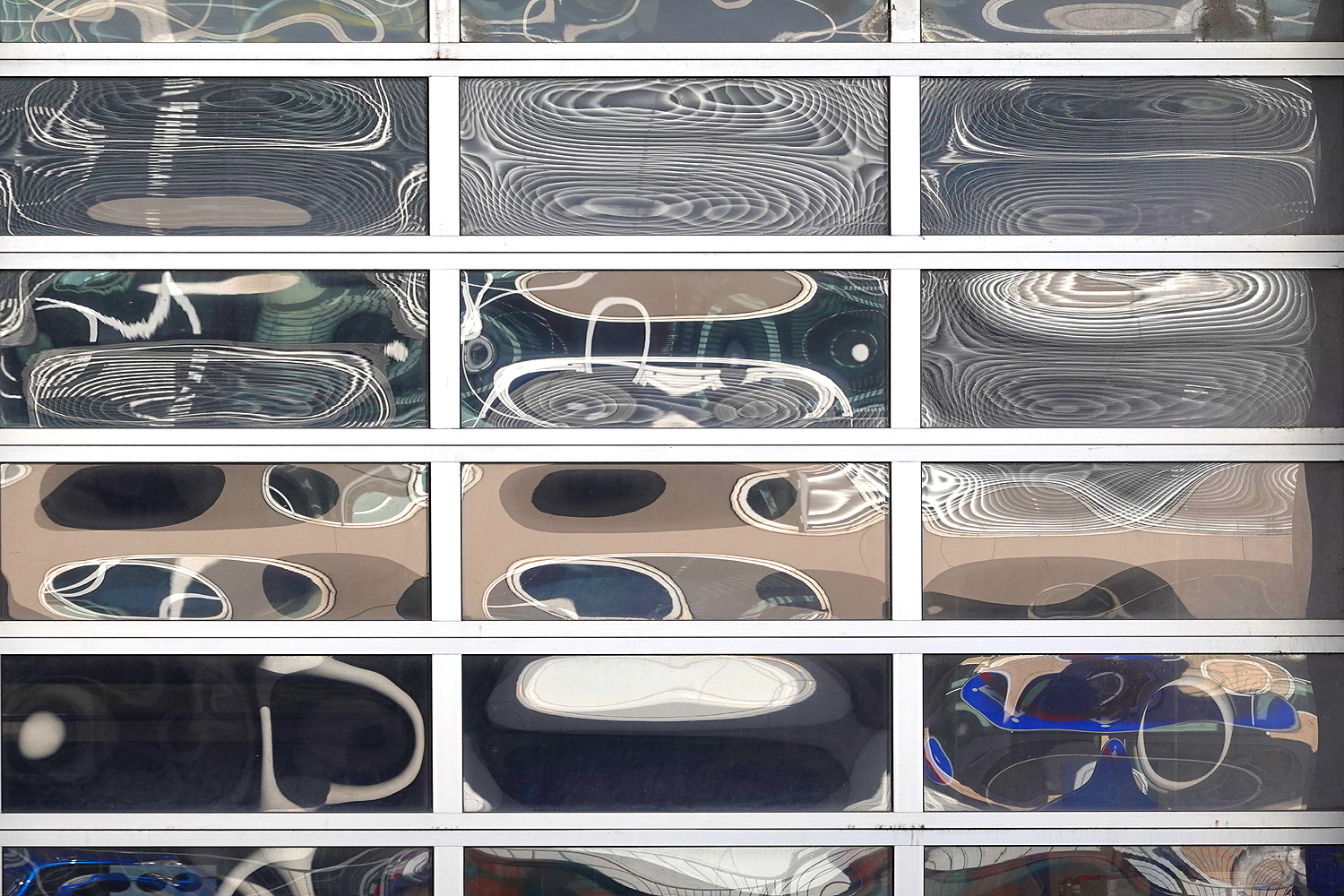

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

Sughra Raza. Reflection. Merida, Yucatan, March 14, 2025.

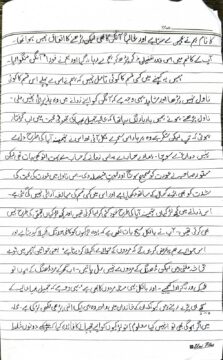

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an

Everyone grieves in their own way. For me, it meant sifting through the tangible remnants of my father’s life—everything he had written or signed. I endeavored to collect every fragment of his writing, no matter profound or mundane – be it verses from the Quran or a simple grocery list. I wanted each text to be a reminder that I could revisit in future. Among this cache was the last document he ever signed: a do-not-resuscitate directive. I have often wondered how his wishes might have evolved over the course of his life—especially when he had a heart attack when I was only six years old. Had the decision rested upon us, his children, what path would we have chosen? I do not have definitive answers, but pondering on this dilemma has given me questions that I now have to revisit years later in the form of improving ethical decision making at the end-of-life scenarios. To illustrate, consider Alice, a fifty-year-old woman who had an accident and is incapacitated. The physicians need to decide whether to resuscitate her or not. Ideally there is an