by Eric Feigenbaum

“Peaches are $8.99 a pound!” my friend texted me yesterday.

“This is the valuable package,” a very nice man named TJ who works at Trader Joe’s but disavows any personal connection said to me as he packed my grocery bag, “It has the eggs!” $5.49 a dozen for jumbo organic free-range eggs was the best deal around.

Despite the recent eight percent drop in oil prices, a gallon of gas in my area still costs almost $5.00 per gallon.

Inflation is not only real, but has been one of the defining issues of our decade. The Consumer Price Index for my region of the country (Western United States) was increasing by as much as 8.3 percent in May of 2022 and still hovers at monthly increases on roughly 2.8 percent. Food costs are still increasing at 5.1 percent per month and most forms of housing in excess of 3.1 percent. Americans have not just faced inflation, but have been hit hardest where it hurts – on necessities and everyday staples.

To their credit, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve have given inflation their full attention and have been working hard to curb it with their main and most accessible tool being interest rates. Raising the cost of capital and borrowing slows the flow of dollars in the economy causing people to spend less. In turn, the cost of goods can slow if not drop because of decreased demand. Raising interest rates is a way to hit the brakes on an overheated economy.

Singapore deals with inflation differently. In fact, it does so in a way completely unique in the world – by focusing first and foremost on consumer prices. Quite simply, the Monetary Authority of Singapore – their version of a central bank – uses consumer affordability as its Northstar.

But how? That’s kind of a crazy thing for a central bank to do. The Fed certainly doesn’t have the kind of power. How does the MAS (which cleverly means Gold in Malay)?

Singapore tries to break what in international economics is often called The Impossible Trinity or The Trillemma.

There are essentially three aspects to monetary policy of which a country can only choose two. It can’t have all three. Those are a Fixed Exchange Rate, Free Capital Movement and an Independent Monetary Policy. The United States, for example gave up the Fixed Exchange Rate in the early 1970’s when the Bretton Woods system of international finances was scrapped. The US dollar now free-floats against other currencies in favor of allowing The Fed greater autonomy and better channels from capital movement.

Singapore nominally does the same thing. The Singapore Dollar does not formally have a fixed exchange rate. Only, the MAS spends its time and attention constantly trading the Singapore Dollar against a basket of other major currencies. Singapore targets a certain value or strength for its money and buys and sells reserves of other countries’ currency to keep the power of value of Singapore Dollar at relative constant.

Given Singapore imports and exports at roughly 300 times its GDP, the power of the Singapore Dollar is vital to its citizens’ ability to afford the globally imported goods – including virtually all foodstuffs – on which they rely.

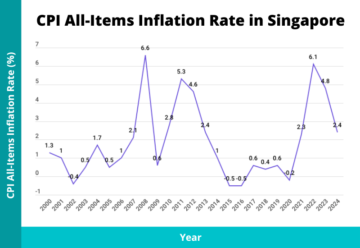

The success of the system is clear. Singapore’s rate of inflation averaged 1.9 percent from 1980 to 2010. Global inflationary pressures beginning in 2020 kept Singapore from maintaining its usual low rate, but in 2024 it still managed to keep inflation to 2.39 percent, while the United States’ was 2.9 percent. In 2022 Singapore had an astonishingly high 6.12 percent – however the United States – with far more of its own domestic supply of most goods – saw 8 percent inflation.

The net result is Singaporeans – who already enjoy a higher per capita GDP than Americans – have generally lower costs on most of their basics. For example, in 2024 Singaporeans paid the equivalent of $3.08 USD per dozen eggs and $3.28 USD for a whole chicken while Americans paid $4.15 and $9.00 for the same items respectively. Moreover, a plate of char kway teow noodles cost Singaporean diners $3.56 USD while if we use Pad Thai as a rough equivalent, Americans spent more like $12 to $15 per plate. Clearly, Singaporeans are out-noodling us.

Another advantage of the Singaporean hack to the Trilemma is that by focusing on exchange rate, Singapore’s monetary policy generally works faster than ours. The Fed changing its prime lending rate begins a cycle of banks changing their interest rates which are what businesses and individuals feel through various forms of borrowing from mortgages to business credit. Loosening the money supply has powerful effects but takes months to even a year before they are fully felt. Singapore can change currency holdings daily – making small and controlled adjustments possible.

Most surprisingly, Singapore’s banks increase their capital supply by borrowing from the private market, not from MAS the way US banks draw from the Federal Reserve. Because Singapore is a net creditor with a AAA credit rating from all ratings publishers, its financial institutions actually profit from borrowing private money and lending it back out. The net effect is Singapore has no national debt and instead profits from anything it borrows – a concept wildly out of sync with its Western friends.

Lee Kuan Yew, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore once said:

“When you have a popular democracy, to win voices you have to give more and more. And to beat your opponent in the next election, you have to promise to give more away. So, it is a never-ending process of auctions—and the cost, the debt being paid for by the next generation. Presidents do not get reelected if they give a hard dose of medicine to their people. So, there is a tendency to procrastinate, to postpone unpopular policies in order to win elections. So, problems such as budget deficits, debt, and high unemployment have been carried forward from one administration to the next…”

However, Singapore not only resisted that approach, but over numerous years of budget surpluses, built such a large reserve that part of its annual budget is funded from interest and dividends on the reserves! This is literally the opposite of what the United States is doing and the financial advantages – which include making money for doing nothing – are clear.

Senior Minister Lee Hsien Loong who served as Prime Minister from 2004-2024 and who is the son of Lee Kuan Yew explained Singapore’s approach to the revenue generated by its reserves:

Our first priority was to keep the capital sums in the reserves safe. We had not thought very deeply about exactly how much of the income to spend. We just took a standard accounting view. That the income from the reserves would be the interest and dividends that we earned on our investments. And we called this the Net Investment Income (NII). And we decided that the government of the day could spend 100% of the NII. But in practice we did not spend any of the NII, because we were still running comfortable budget surpluses.

Later, when Mr Ong Teng Cheong was elected President, he questioned this rule. He asked: why do we allow ourselves to spend 100% of the NII? He argued, correctly, that we should also set aside something for the future. Because as the years passed, as the economy grows, if your reserve amount remains constant, it gets smaller relative to the economy. And you ought to allow the reserves also to grow. So, the question is: how much to provide for the future, while also enabling the present generation to benefit from the reserves? There is no magic rule to this, but we arrived at a split of 50-50. There is a certain simplicity and fairness to that; a natural division that we settled on between the President and the government. It is simple, it is intuitive, everybody can understand it. We split the difference between now and the future. And so, in 2001, Parliament passed a constitutional amendment to protect 50% of NII, and add that to the reserves. And the other 50%, the government of the day could spend. 50% for the present, 50% for the future.

Quite honestly, is it any wonder Singapore has a AAA credit rating? Who wouldn’t want to lend to people who operate this way?

With Singapore’s not only focus, but severe need for trade and its desire to not only drive its future, but to do so with incredible fiscal responsibility, it makes sense that Singapore couldn’t give up Sovereign Monetary Policy of Free Capital Flow. Its brilliance was deciding the Impossible Trinity didn’t have to be – Singapore didn’t have to allow its hands to be bound when it came to foreign exchange. If the Singapore Dollar was going to “float” on the market, Singapore realized it could give it paddles and guide it with a tow-line.

In 2025, despite worries about tariffs and their global economic effects, MAS is still targeting an annual inflation of between 0.5 and 1.5 percent. America will be lucky to get by with 2.5 percent inflation. For Singaporeans, it looks like both eggs and char kway teow will remain affordable – trade wars or not.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.