by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

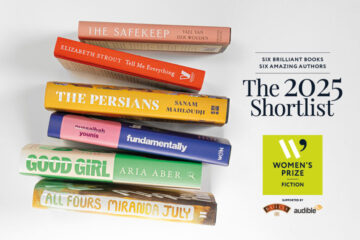

Shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for fiction this year, Sanam Mahloudji’s The Persians is a multi-generational novel about a wealthy Persian family, told from the points-of-view of five of the family’s women. Starting the novel, I was expecting a fun romp with a group of extremely glamorous Persian ladies. You know, Chanel suits and amazing shoes. And the novel did open with a wild night: the American branch of the family is partying on vacation in Aspen (where else?), when Aunt Shirin is arrested for prostitution, accused of soliciting an undercover cop in a bar.

A ridiculous idea that Shirin is struggling to take seriously even after she spends the night in jail. After all, she is rich beyond belief, the descendant of a great Persian war hero, if you believe all those old stories, plus the family are hereditary landowners.

This wealth being the center of everything.

The story starts with the matriarch of the story Elizabeth, who falls in love with the chauffeur’s son, not something done back in the day. And then when things get iffy with the Shah and revolution seems possible, Elizabeth’s daughters, including Shirin and family decide to take a short trip to Paris, to wait it out. Fully expecting to return to Iran, Shirin agree when Grandma Elizabeth informs Shirin that her daughter Niaz wants to stay behind in Iran with grandma. That Paris holiday turns into twenty-seven years with Shirin and family eventually settling in Houston and Niaz staying behind with her grandma in Tehran.

Because the family is separated into the bilinguals in America and the Persians who stayed behind, Shirin’s words at the start of the novel have real impact.

“We didn’t come here for a better life. We left a better life.”

It is a startling comment since at one point her daughter Niaz has been jailed by the Revolutionary Guards and has had to lead a life much more circumscribed than Shirin’s drug-fueled wildly extravagant lifestyle. But the more you read, the more you wonder about happiness. First of all, Shirin has basically been profiled and racially targeted by the white policeman in Aspen. That is what her lawyer says. But Shirin dismisses this since because she says, she doesn’t even have dark skin and also because she is convinced that the cop desired her for real and that –just like everywhere else in the world—he was a man struggling with how to contain and control a strong woman. In fact, she was just playing along with him, because she was bored and drunk.

They still have all their money and live like royalty so why does she feel she had a better life in Iran? Read more »