by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

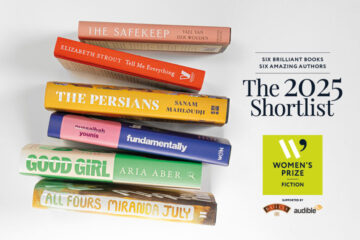

Shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for fiction this year, Sanam Mahloudji’s The Persians is a multi-generational novel about a wealthy Persian family, told from the points-of-view of five of the family’s women. Starting the novel, I was expecting a fun romp with a group of extremely glamorous Persian ladies. You know, Chanel suits and amazing shoes. And the novel did open with a wild night: the American branch of the family is partying on vacation in Aspen (where else?), when Aunt Shirin is arrested for prostitution, accused of soliciting an undercover cop in a bar.

A ridiculous idea that Shirin is struggling to take seriously even after she spends the night in jail. After all, she is rich beyond belief, the descendant of a great Persian war hero, if you believe all those old stories, plus the family are hereditary landowners.

This wealth being the center of everything.

The story starts with the matriarch of the story Elizabeth, who falls in love with the chauffeur’s son, not something done back in the day. And then when things get iffy with the Shah and revolution seems possible, Elizabeth’s daughters, including Shirin and family decide to take a short trip to Paris, to wait it out. Fully expecting to return to Iran, Shirin agree when Grandma Elizabeth informs Shirin that her daughter Niaz wants to stay behind in Iran with grandma. That Paris holiday turns into twenty-seven years with Shirin and family eventually settling in Houston and Niaz staying behind with her grandma in Tehran.

Because the family is separated into the bilinguals in America and the Persians who stayed behind, Shirin’s words at the start of the novel have real impact.

“We didn’t come here for a better life. We left a better life.”

It is a startling comment since at one point her daughter Niaz has been jailed by the Revolutionary Guards and has had to lead a life much more circumscribed than Shirin’s drug-fueled wildly extravagant lifestyle. But the more you read, the more you wonder about happiness. First of all, Shirin has basically been profiled and racially targeted by the white policeman in Aspen. That is what her lawyer says. But Shirin dismisses this since because she says, she doesn’t even have dark skin and also because she is convinced that the cop desired her for real and that –just like everywhere else in the world—he was a man struggling with how to contain and control a strong woman. In fact, she was just playing along with him, because she was bored and drunk.

They still have all their money and live like royalty so why does she feel she had a better life in Iran?

Why does she seem so genuinely unhappy? Well, maybe because she loved her country and flourished in her home culture and didn’t really want to leave. And to drive home this idea, her daughter who stayed behind in Iran seems to have more inner freedom and a strong sense of purpose, despite authoritarianism.

Reading the novel, you just can’t help but wonder how Shirin would have been different had she stayed back in Iran. How Niaz might have been transformed by America had she come with the rest of the family. And then there is Shirin’s niece Bita, who has a much more tenuous tie to Iran, having come to the US as a baby and not being fluent in the language or culture beyond their family. The degrees of cultural assimilation and language loss are explored so brilliantly in the novel, as is a more complex understanding of personal identity.

2.

Not unlike Bita, my son came to the US from Japan when he was young. At the time, he couldn’t speak English. Immediately put in ESL programs at a public school in California, he became fluent in English, losing any trace of an accent by high school. But he also lost any real trace of his Japanese language skills.

And I have often looked at him and wondered what he would’ve been like if we had stayed in Japan. He is still polite and respectful, a rule follower just like he was in childhood, and I think he’s the same kid, but I often wonder about myself, how I might have been a different person if I had not spent those decades in Japan, especially when I was young and impressionable, and more, if I had not rewired my brain thinking and dreaming in Japanese.

Immersing myself in Japanese culture was rewarding—but becoming fluent in Japanese was also to wake up one day realizing that another version of myself had taken up residence in my psyche like some annoying roommate I’d been forced to bring in, and who will never leave. Forever toggling back and forth between things American and those Japanese—from thinking and dreaming in Japanese then back again to English, had left me alienated. Always betwixt and between, I never felt truly at home in either language or country. Sometimes I hardly recognized myself from the person I was before Japan. And then, the older you get –Shirin and I are around the same age–the more difficult it is to do that toggling.

3.

3.

This kind of seesawing whiplash, for example in The Persians between jaded American consumerism and the sadness and guilt of displacement, is on full display in another 2025 Women’s Prize shortlisted novel called Fundamentally by Nussaibah Younis, which is also a debut. The story is written by an academic and former humanitarian worker about an academic aid worker in Iraq named Nadia. In the novel, Nadia was born and raised in the UK and is the daughter of an Iraqi parent. Nadia, the child of two Muslim parents, had a religious upbringing. She is currently not speaking to her mother since being kicked out of her home, when her mother becomes angry aftre Nadia is seen without a head scarf.

Alienated and emotionally drifting, Nadia takes a job working for the UN in Baghdad trying to rehabilitate former ISIS brides. In a similar exploration of alternative versions of oneself, Nadia sees herself in one of the former ISIS brides named Sara. In Sara, Nadia sees a younger version of herself, when she was nearly recruited at an Islamic summer camp. A charismatic boy she met there began grooming her, and she says she could have easily made Sara’s mistake.

Well, except that Sara insists she wanted to go. She was fifteen and her best friend went and so Sara willingly traveled overland from Turkey into Iraq to marry.

In contrast to Sara, there is a Swiss former ISIS bride who was kidnapped and terribly abused in Iraq and who hates ISIS. All this woman wants to do is return to her home in Switzerland. But Nadia drops the ball on this woman’s case, instead risking life and limb to get Sara out of Iraq so she can be reunited with her parents, because, again, Sara reminds Nadia of herself.

But as she is helping to save Sara, Nadia is also hooking up with men and women right and left and taking massive amounts of drugs and drinking copious amounts of alcohol in front of her young charge. Sara, who just escaped Islamic indoctrination, tells Nadia that yes, she desperately wants to go home; however, she never wants to live the empty, lonely life Nadia has succumbed to.

Like The Persians, it is an unforgettable exploration of meaning and human flourishing. It is also about the seesawing sense of self that bilinguals sometimes experience. And maybe more than anything, both books resist the notion of pure identity and illuminate the way the paths we did not take in our lives, perhaps as much as those we do take, still inform who we are.

4.

Perhaps more than any other art form, novels are able to excavate the ambiguous and complex human experiences that defy easy categorization. Through the microcosm of the characters, life trajectories are laid out for us. Because we are emotionally engaged, literature generates insight and empathy as characters navigate external and internal forces. For example, I have never been able to fully articulate how tiring being an immigrant can be, especially as you age. But I am also haunted, like Shirin and Nadia, about alternative versions of myself.

I recently asked my son if he thinks he would have been a different person if we hadn’t left Japan to return to California. And he says he often wonders this but is unable to imagine it. We all lead these double lives, with alternative versions of ourselves haunting us like ghosts. The novel is an art form that captures this idea of ourselves as stories better than anything else in the world.

5.

There was a recent article in the New York Times about the gender divide in reading fiction in the US. Men are not reading novels anymore, the article lamented. A 80/20 divide is frequently cited in articles, with women buying the lion’s share of fiction. These so-called industry numbers are frequently cited, but it’s not clear where the numbers come from or what study they are based on. Trying to get to the bottom of it, a friend mentioned that a couple of years ago, British author Ian McEwan conducted an admittedly unscientific experiment. He and his son waded into the lunch-time crowds at a London park and began handing out free books. Within a few minutes, they had given away thirty novels.

Nearly all of the takers were women, who were “eager and grateful” for the freebies while the men “frowned in suspicion, or distaste.” The inevitable conclusion, wrote McEwan in The Guardian newspaper: “When women stop reading, the novel will be dead.”

I think it is beyond question that literary fiction and publishing in general is now dominated by women. But then overall, aren’t people reading less? And what of the other arts? Especially in a country without national healthcare or federally managed and more egalitarian school systems it is harder and harder to find time to read, much less practice the arts since most people are busy hustling to pay for these things.

In Japan, where everyone has healthcare and where all schools have similar budgets and facilities no matter where you live, people have more space to read and practice art if they want. And what a gift that is.

Like everyone else, I do much reading online, essays and stories. But it is very hard to provide more than an opinion or perhaps a half-idea in an article compared to a book-length project, something taking many, many months to write in most cases, if not years. Deeply researched online writing has become scarce, and we are experiencing a sort of pancake effect in our society, where the nuance and richness of books is missing. Without the intricate tapestry of a novel, it is almost impossible to convey a state of being in which our conflicting selves struggle and reconcile, in which our ghost lives are inextricably woven into the lives we choose or have forced upon us. Both these novels explore the pull of contrasting cultures, lifestyles, and identities, with a depth and complexity that I could never convey in this online essay. And so, with eagerness for you and gratitude to their authors, I point you to these wonderful and exciting new debut novels!

++

For more:

For those who read David Brooks’ latest about the death of the novel, you might be interested in knowing that the above two novels were written by Europe-based authors, outside the MFA tradition in the US. Another recent novel that explores similar themes is The Coin by Yasmin Zaher. This book received the Dylan Thomas Prize. It is an astonishing book. I am looking forward to the Booker Prize Longlist later this month (and Obama’s Summer reads list). I hope all three books make the list. Also, Europe-based American writer Nell Zink’s latest novel Sister Europe and Guo Xiaolu’s re-telling of Moby Dick, Call me Ishmaelle. Also loved Katie Kitamura’s latest, The Audition.

For those interested in the great possibilities of non-US storytelling traditions –really recommend Henry Lien’s Spring, Summer, Asteroid Bird