by Thomas Fernandes

We might know more about biodiversity than ever before, yet we see it less. When life is talked about as “carbon sinks,” “pollinator services,” or “extinction curves,” it flattens into numbers: computable but unfeeling. But the loss we face isn’t just biological. It’s perceptual. We no longer notice life. Our first loss, then, may not be biodiversity itself, but our ability to see it. And nowhere is this blindness more widespread, or more foundational, than with plants.

Plant blindness is not simply a lack of interest in flora but a systemic failure to perceive the living structure of the world around us. We might pause for a flower’s scent or color, but how often do we notice the complex strategies behind its form?

Let’s begin, then, not with the abstract notion of biodiversity, but with the particular of flowering plants. At first, they had no roots, relying on fungi to supply water and nutrients in exchange for sugars produced by the plant through photosynthesis. With time plants started to develop their own roots systems but still lacked flowers. They were mostly ferns and conifers like pines.

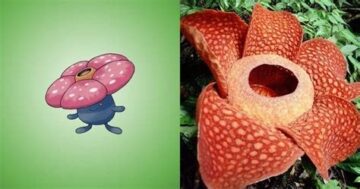

In a baffling new evolution angiosperm (flowering plants) appeared about 170 million years ago. Flowers are the product of natural selection to attract and use pollinators to reproduce. They use scent, color, shape and sometimes temperature to signal to pollinators. Smell for instance is a primary attractor for many pollinators. In Europe, flowers that rely on bees and butterflies often emit sweet scents. But not all strategies are pleasant to us.

The Rafflesia, the world’s largest flower, smells like rotting meat to attract flies. The Titan Arum goes further, heating itself to human body temperature to volatilize more effectively corpse smelling compounds detectable hundreds of meters away. The temperature also imitates that of a body, an attractor in itself for carrion beetles. Read more »

Sughra Raza. The Visitor. Mexico, March 2025.

Sughra Raza. The Visitor. Mexico, March 2025.

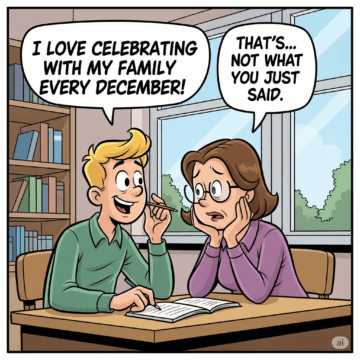

At a Christmas market in Germany, I told my German girlfriend’s mother that I masturbate with my family every December.

At a Christmas market in Germany, I told my German girlfriend’s mother that I masturbate with my family every December. The File on H is a novel written in 1981 by the Albanian author Ismail Kadare. When a reader finishes the Vintage Classics edition, they turn the page to find a “Translator’s Note” mentioning a five-minute meeting between Kadare and Albert Lord, the researcher and scholar responsible, along with Milman Parry, for settling “The Homeric Question” and proving that The Iliad and The Odyssey are oral poems rather than textual creations. As The File on H retells a fictionalized version of Parry and Lord’s trips to the Balkans to record oral poets in the 1930’s, this meeting from 1979 is characterized as the genesis of the novel, the spark of inspiration that led Kadare to reimagine their journey, replacing primarily Serbo-Croatian singing poets in Yugoslavia with Albanian bards in the mountains of Albania.

The File on H is a novel written in 1981 by the Albanian author Ismail Kadare. When a reader finishes the Vintage Classics edition, they turn the page to find a “Translator’s Note” mentioning a five-minute meeting between Kadare and Albert Lord, the researcher and scholar responsible, along with Milman Parry, for settling “The Homeric Question” and proving that The Iliad and The Odyssey are oral poems rather than textual creations. As The File on H retells a fictionalized version of Parry and Lord’s trips to the Balkans to record oral poets in the 1930’s, this meeting from 1979 is characterized as the genesis of the novel, the spark of inspiration that led Kadare to reimagine their journey, replacing primarily Serbo-Croatian singing poets in Yugoslavia with Albanian bards in the mountains of Albania.

The Paradise, Pandora and Panama Papers, exposing secret offshore accounts in global tax havens, will be familiar to many. They are central to the work of economic sociology professor, Brooke Harrington. She has spent many years researching the ultra-wealthy and several books on the subject have been the result. Her latest book Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism is a continuation of her research; it focuses on ‘the system’, the professional enablers who support and advise the ultra-wealthy and make it possible for them to store and conceal their phenomenal fortunes in secret offshore accounts.

The Paradise, Pandora and Panama Papers, exposing secret offshore accounts in global tax havens, will be familiar to many. They are central to the work of economic sociology professor, Brooke Harrington. She has spent many years researching the ultra-wealthy and several books on the subject have been the result. Her latest book Offshore: Stealth Wealth and the New Colonialism is a continuation of her research; it focuses on ‘the system’, the professional enablers who support and advise the ultra-wealthy and make it possible for them to store and conceal their phenomenal fortunes in secret offshore accounts.

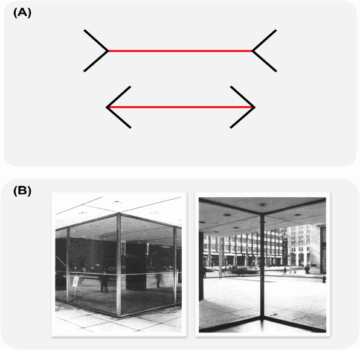

Sughra Raza. Light Tricks, Seattle, March, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Light Tricks, Seattle, March, 2022.

I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in

I have been thinking about artificial intelligence and its implications for most of my adult life. In the mid-1970s I conducted research in computational semantics which I used in