by Angela Starita

A few months ago, I visited Freehold, NJ, an hour’s drive south of Manhattan. The town has serious Revolutionary War credentials as the site of the Battle of Monmouth, a tactical mixed bag from the American perspective but a definite win for local identity. I grew up in the town just south of Freehold, and the battle, from the annual re-enactment to the many historic plaques and business names in honor of Molly Pitcher, water girl to the Revolution, looms large. As county seat, Freehold is home to the Monmouth County Historical Society and a cache of papers related to a commune once sited in what is today a town called Colts Neck. Named the North American Phalanx (NAP)—mentioned a few months ago in this column—it’s generally viewed by historians as the most successful of a few dozen communes organized around the ideas of one Charles Fourier (1772–1837), a French socialist thinker trying to solve an essential puzzle: how do we pursue our own happiness while working towards communal goals of eradicating poverty, war, and famine? As far as Fourier was concerned, finding a way to get pleasure from work, from camaraderie, from sex, from love is key to ecological and even cosmic progress. Our commitments to capitalism not to mention monogamous family units had obstructed our development as human beings, which, in turn, stymied our physical environments. Most famously, Fourier believed that our oceans would taste of lemonade (what he called a boreal citric acid) once we had freed ourselves of jealousy and greed, and pursued higher forms of knowledge and sensation. But as things stood at the turn of the 19th century, Fourier saw us as mired in pointless, confused pursuits unworthy of our innate talents. As Dominic Pettman put it in a 2019 article for Public Domain Review, Fourier “also took it for granted that aliens on other planets were far more evolved than we are, and that we are the slow kids on the cosmic block, having been mired in incoherency for so long.”

To get us closer to enlightenment as he envisioned it, Fourier proposed a model community to be set up in multiple points around the world. These working, communally-run farms (he called them domestic agricultural associations) would demonstrate the folly of isolated pursuits of consumption, and eventually convert the masses to pursuing their passions in concert with a community. The result would be world-wide harmony, a key term in the Fourier lexicon.

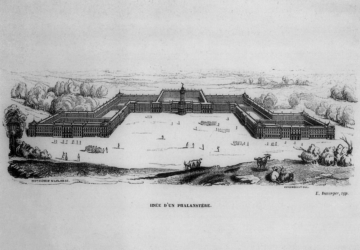

Fourier offered detailed instructions on the layout of each commune, a firm believer that the organization of space has direct influence on behavior. “The lodgings, gardens and stables of a society run by series of groups must be vastly different from those of our villages and towns, which are perversely organised and meant for families having no societary relations. Instead of the chaos of little houses which rival each other in filth and ugliness in our towns, a Phalanx constructs for itself a building as perfect as the terrain permits,” he wrote. He called for a set of buildings arranged around a common courtyard, a central structure for gathering, and two side wings for dormitories. The rest of the buildings were dedicated to “seristeries”—meeting halls for those dedicated to a particular task or passion—and storage. The population should include 1640 men and women, a number he arrived at using some odd calculus meant to insure that all personality types, what he called “passions,” would be represented in the phalanx.

As it appears in various drawings, including two by some his most dedicated followers, Victor Considerant, and, in the United States, Parke Godwin, the phalanxcit is notably similar to the site plan by Louis Le Vau for the palace at Versailles. Both culminate in a central volume that dominates the plan. At Versailles, it holds the famed Hall of Mirrors and Louis XIV’s main chambers that stand on axis with a set of gardens and a statue of Apollo—sun god for sun king. Though smaller in scale, Godwin’s and Considerant’s iterations both treat that central block as an enclosed square defined by a multistoried building, and like Versailles, wings on either side speak of supporting roles, ones necessary to each community but clearly lesser in the hierarchy of spaces.

In the Godwin version, gardens are as essential as they are at Versailles, humbler design for sure, but critical to the image of the complex. Another, this one done in (1847) by the artist Charles-François Daubigny, portrays a phalanx as the size of a town but with architecture for a grand city. The massive central plaza is surrounded on three sides by four-story buildings identical in their facades with two projected wings and a tower as central entry way to the buildings. The town is fitted with a medieval cathedral, a chuffing smokestack, and multiple outbuildings with courtyards. The only people to be seen are on the far side of a bridge that separates the phalanx from the rest of the landscape, a verdant, manicured plain with a river and mountains in the distance.

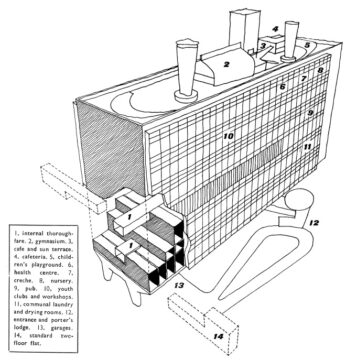

Though one is a rendering and the other a site plan, the two drawings emphasize the role of cultivated land, a key aspect of Fourier scheme. Yet Considerant, Fourier’s most influential disciple, conceives the interior courtyards free of flora; they look more like grand-scale plazas for political rallies than gardens for meditations on nature or a free love tryst. It’s a rather cold interpretation of the phalanx, this instrument for blasting us into unimagined heights of love and fulfillment. I prefer Godwin and especially Daubigny’s visions which seem quainter in the ways they suggest the full complement of a community’s needs in a setting that suggests health, fresh air, none of the degradation associated with factories or churches. But for all its dependence on LeVau’s circumscribed court, Considerant’s drawing captures something particularly modern in the way it imagines the buildings as both shelter and city limits. It depends on the verticality of the buildings to create an enclosed unit that could be controlled, much the way Louis XIV built Versailles as an isolated city of nobles removed from Paris, the better to dominate it. Fourier’s phalanx is said to have influenced the modernist architect Le Corbusier, who, in the wake of World War I, saw in Fourier a spiritual ancestor who believed that we were taking a wholly destructive path. And while I have no evidence, I’d bet a lot that it was Considerant’s drawing that inspired Corbu: its tightly organized, city-within-a-building qualities that were essentially to the Franco-Swiss architect’s designs. Like the phalanx, Le Corbusier’s proposed schemes and built ones provided far more than shelter. They included nursery schools, gyms, gardens, and commercial zones—his “streets in the sky” where whole floors in a building would be used for stores not apartments. There’s little reason to ever leave. Both men believed that they alone understood how to eschew our lousy fate with a solution rooted in the organization of space. In their drawings, devoid of people and history, they succeeded. And their iterations off the page were to some degree successful with the NAP lasting 13 years, and Corbusier’s vast oeuvre exerting immeasurable influence today.

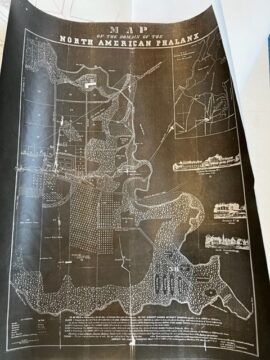

In the archivist’s office in Freehold, a librarian brings out a photostat of a map of the NAP so large I need to unfold it on the floor. The map records the boundaries of the commune’s land in what was then Red Bank, a quilt of strawberry patches, apple, quince, and pear orchards, wood lots, and fields divided by streams, manmade boundaries, and the Swimming River on the eastern edge of the property. Along the right edges, the map maker the site’s buildings, one labeled “Central Building #1. 71 Feet above Tide.” Beneath is a house identified as “Seristery #18 (Brick).” They are three story buildings with long porches and multiple wings, farmhouse hotels.

What we don’t see, of course, are The Associationists themselves, largely farmers as well as a handful of young women probably drawn to the ideas of Fourier, who coined the word feminism, to escape the drudgery of mills and factories. A drawing of their lives would’ve shown a lot of farm work and meetings. Arranging passion-driven work schedules proved so arduous that the group’s president recalled “our days were spent in labor and our nights in legislation.” But there also would’ve been a day care, music, games, weekly dance, and regular socializing. One single woman, who lived in a Wisconsin phalanx, reported “by opening either door we can see and talk to as many people as we care to.”

A third drawing showing the site’s future would come from the sort of cheap paperbacks my father kept around our house, compilations of architectural drawings of middle class houses with plans and renderings. I bought a few this year on eBay. Mine were published by the Garlinghouse Company in Topeka, Kansas. The company should be lauded for its variety of options, from “Stucco Masterpiece” to “New England Classic” to “Underground with Greenhouse,” this last covered in 2-feet of direct and sod to save on heating cooling costs. No matter the design, the houses are all shown, of course, in isolation. If other houses are within view, the draftsman is careful not to remind us, instead filling out his drawings with old growth trees. A current website that collects house plans claims, “It would be no exaggeration to say that Garlinghouse plans have been built into more homes than plans from any other source in the world.” I have no idea if Garlinghouse plans were ever used in Colt’s Neck, but after leaving the archives to find the site, I drove around housing developments that had a distinctly Garlinghouse vibe, if on a grander scale: 3,000 square foot homes with circular driveways; a weird mix of Palladian arches, balustrades, and vertical casement windows; and lots of emptiness in all directions. If I were to guess the distance between houses, I’d have to use the only form of measurement I feel versed in, a city block. On the site of the old NAP, houses are set a solid block apart.

The community’s land now holds upscale neighborhoods built in the ‘70s and ‘80s, a community college campus, a famous apple jack company called Laird’s, and a graveyard for one of the original phalanx families that, according to my GPS, sits on a spit of land jutting into the Swimming River. (I tried to reach it but was blocked by a private farm where the only sentient beings seems to be two pretty goats.) As is often the way with lost people and ideas, the only real reminder of the Fourierist experiment remains in street names: Phalanx Road and Utopia Way.

I wheeled through the streets, took pictures, compared maps, got stares from the only people outside that day, a man and his daughter playing basketball. On one of the many cul de sacs, I tried to convince myself that I recognized one of the houses as having once belonged to a close family friend, a man named Tony who’d been a very successful patternmaker for Jones New York. He moved to that large, well-appointed house in 1979 with his wife and two daughters and kept racks of clothes in his garage—samples from the dozens of shops he constantly visited around the northeast where he trained people to make the company-approved designs. His marriage was a contentious one to be sure, so he easily succumbed to the demands of work, essentially living in his car. He thought nothing of driving 10 or 12 hours in a day, running from shop to shop before eventually suffering a massive heart attack and dying behind the wheel. He was a man almost pathologic in his desire to help, do whatever possible favor you needed, give you a ride, introduce you to any friend. He’d urge my mother to choose whatever she liked among the blouses, dresses, and blazers. It was as if his generosity couldn’t find an outlet big enough. For Tony, I’d guess, his home was defined by his house and garage, much like the drawings of a Garlinghouse draftsman. No day care, no dance hall or restaurant, no nights of debating work schedules or the proper education of phalanstery children or how to fund the next year’s crops. Just a clear stand of trees marking the property line.