by David Beer

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

The other day, in a cavernous sports superstore, I thought of J.G. Ballard. Echoey. Compartmentalised. Fluorescent. Stuffed with product. It was, probably quite obviously, the sort of place Ballard might have imagined the norms of society suddenly collapsing in on themselves, unable to carry their own contradictions.

Banal yet shiny, ordered yet unstable, glowing yet unspectacular. It just seemed a ripe setting for a sequel to his 1975 novel High Rise, in which, famously, a luxury tower block became the scene of a destructive uprising against the hierarchical social stratification that its vertical floors represented. Or, maybe I could be trapped alone in the store, unable to escape its automatic doors, in a twist on Concrete Island, the 1974 tale of the motorist marooned in a dead-space between intersecting motorways.

I was welcomed by a basket of varied coloured footballs and a rack of monochrome mid-calf socks. To the side an array of baseball caps – each a slight variation on the last.

The store swung around to the left in an L shaped-layout. A dog-leg left, perhaps leading to the golf section. There was a second floor too, with equal square footage. Desolate. In the distance, two racks of sporty house-slippers.

Moving through what I imagined the store planners refer to as zones, everything arrived in glances. Fleeting eye movements, taking in the many minute differences. Rapid and brief views of garments momentarily visible, as lines of sight allowed. Flashes of light off mirrors. High wattage signs. The light was artificially bright. Yet there seemed to be no shadows.

The folds of products are deep-lined. The rails packed tight. The display shelves carry the weight of consumables. Lots of things for sport, and many more besides. Some faux sheepskin boots. Decorative desert boots. A NASA emblazoned bomber jacket – for when you wish to look like an astronaut attending a post-flight press conference. My attention jumped between fuzzy fragments, bits and pieces.

All these things and no algorithm to tell me what I should purchase. That is what I was missing in the actual concrete shop. I had no automated prediction of my taste. I had to make my own decisions. Trying to navigate the mass of items the absence of automation became obvious. I was manual, analogue shopping. Read more »

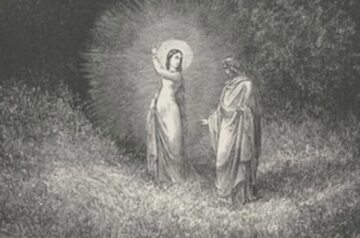

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing.

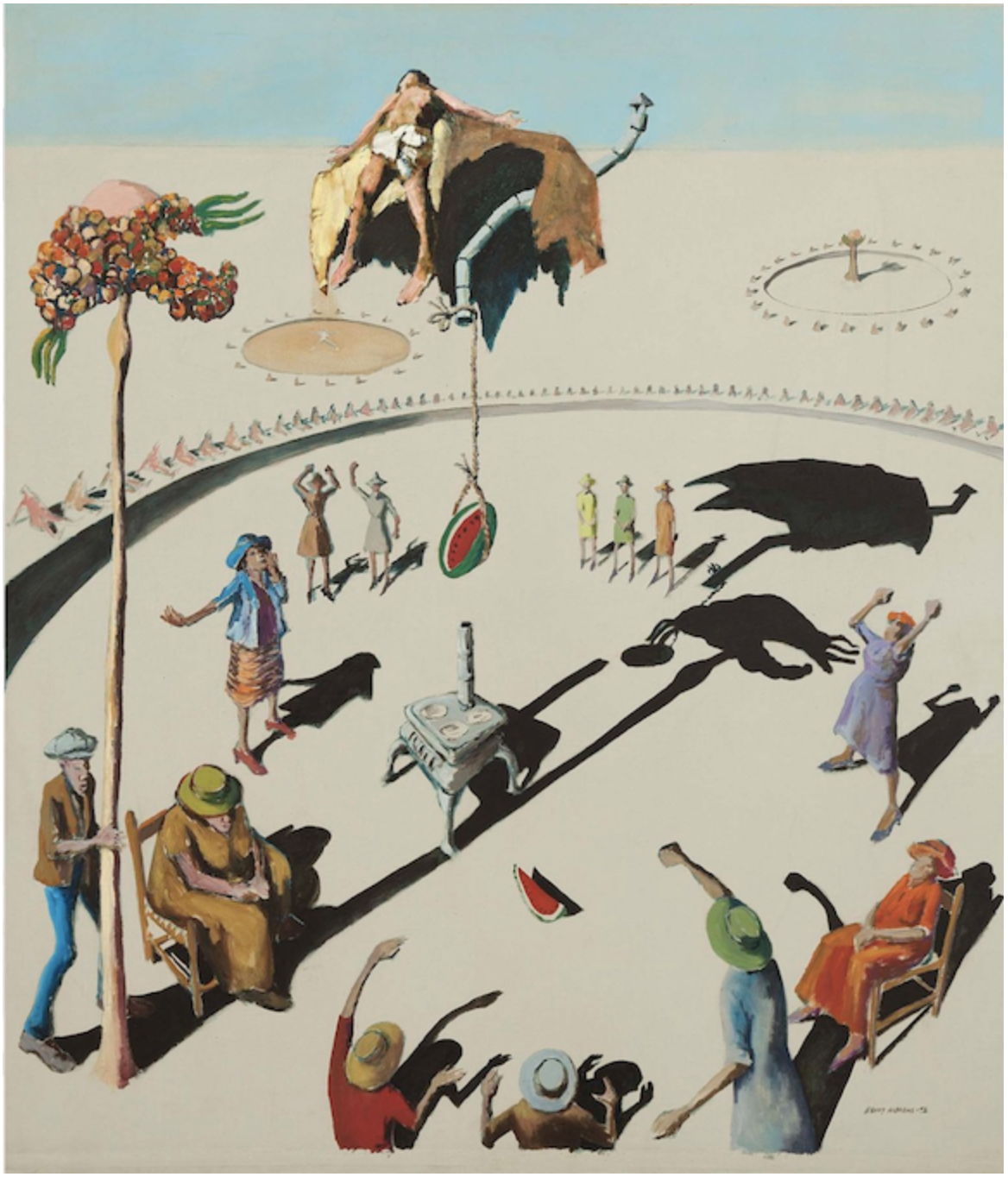

Dante begins The Divine Comedy in a dark wood, lost. He cannot see the way forward. His journey out of confusion and despair depends on a guide—not just Virgil, who leads him through Hell and Purgatory, but ultimately Beatrice, whose beauty awakens in him a love that points beyond itself. Beatrice is not simply an object of desire. She is a source of orientation, a reminder that desire itself can be educated, elevated, and directed toward what is most real and most nourishing. Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

Benny Andrews. Circle Study #2, 1972.

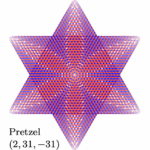

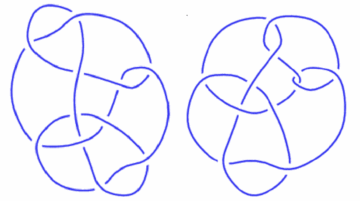

Mathematics is

Mathematics is

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.

Today an electrician came to visit. He was tall and broad-shouldered and had arms like sausage links that were fairly covered in tattoos. One of the tattoos was a date: January something-or-other. I tried to read it as he walked through my front door, but he looked me in the eyes and so I glanced away quickly without having absorbed any of the details. He had come to inspect my attic wiring, for which he had to get on his hands and knees and crawl around the attic floorboards. It was a short but dirty job. When he came downstairs his palms were blackened and so he asked if he could wash up somewhere. I pointed him to my kitchen sink and to a small bar of soap on one side of it. While he was washing his hands (very thoroughly, I noted), he turned to me and starting cheerfully recounting how important it was to him to be clean. He had a pink, friendly face, sort of like a big baby. He had shaved blond hair that had grown out ever so slightly and a twinge of orange in his beard stubble. I told him I was accustomed to dirt, having two sons and a male dog, although upon saying that I realized I wasn’t sure whether my dog’s sex was much of a factor in how dirty or clean he tended to be. The electrician nodded when I spoke but seemed eager to get back to his own story. He went on to tell me that he had a child but that he was no longer together with the mother. It’s not like me to have a one-night stand though, he said, it’s not a hygienic thing to do. And anyway, he went on, I could never have stayed with her—she was a slob, an unbel-IEV-able slob. She couldn’t focus, couldn’t pay attention to me or anyone else, and certainly not her surroundings. Keep your eye on the ball, I told her, but she didn’t know what I meant. Believe me, he said, that girl and all her stuff was all over the place.