by Rafaël Newman

I was asked recently to speak at the University of Toronto about poetry in translation, a topic close to my heart for a number of reasons. I happened at the time to be working on a text concerned, not with translating poetry, but with lyric expression in its most practical form: that is, as a commodity with a material history, as an object that can be traded, one with an exchange value as well as a use value (however the latter might be defined, or experienced).

I was asked recently to speak at the University of Toronto about poetry in translation, a topic close to my heart for a number of reasons. I happened at the time to be working on a text concerned, not with translating poetry, but with lyric expression in its most practical form: that is, as a commodity with a material history, as an object that can be traded, one with an exchange value as well as a use value (however the latter might be defined, or experienced).

The reason for this pragmatic frame of poetic mind was as follows: I had for pecuniary purposes been learning about fintech (financial technology), about tokenized assets and distributed ledgers, and was thus briefly engaged by an ecosystem distant enough from my typical life experience that it had begun to present itself to me under the lurid aspect of science fiction, as a Peter Max and William S. Burroughs-inspired lucid dream of aliens and teleporting and iridescent currencies riding an ominous conveyor belt of ballot boxes. In other words, my day job was encroaching on my vocation!

The pushback I devised, a method for domesticating this unfamiliar terrain and rendering it at least temporarily welcome, after-hours in my psychological household, was to imagine a range of revered poets—Sappho, Emily Dickinson, John Donne, and Philip Larkin—anachronistically encountering the strange new gods of Bitcoin, Blockchain, and CBDC, and to ghostwrite the appropriate text for each of them. I was so pleased with these efforts that I went on to imagine a newfangled poetry journal featuring videos of poets reading their own work, minted as NFTs or non-fungible tokens—you may know these digital artifacts as the images of a Bored Ape or a Penurious Ex-President—and hosted on a blockchain. I wrote up the concept, and my “white paper” will appear later this year as a contribution to a new Swiss cultural studies journal devoted to the appealingly opaque concept of transindustriality.

And so it was that, when I agreed to give a lecture on translating poetry, I was of a mind to consider that typically immaterial artform as a physical object in circulation, in the process of being fundamentally transformed by the technology of its new medium; and thus it wasn’t a great leap for me to consider the ancient craft of literary translation—think Saint Jerome and his lion—in a thoroughly contemporary form, rather than sub specie aeternitatis.

In fact, my materialist perspective had been further prepared by a seminar recently offered at Zurich’s Literaturhaus by Samuel Läubli, the young CTO of a local startup that had tailor-made software systems providing neural machine translation, or NMT, for our common corporate clients. (NMT uses coordinates or parameters to map frequency and likelihood of collocations from one language to another, and is distinguished from existing “statistical” translation engines by its ability to “learn” from human users, and to exploit such “training” in a transformative “black box” whose inner workings seem not entirely clear even to its constructors.)

Läubli, whose dissertation at the University of Zurich was equal parts higher mathematics and Chinese linguistics, had cannily gathered a group of literary translators in order to allay potential anxieties about “our new robot overlords” and to encourage us to consider the possibilities afforded by the latest language technology. During the course of his presentation, Sam asked us to choose from blind samples of human and machine-translated German versions of English prose texts, by contemporary authors such as Ocean Vuong; he then dealt compassionately and evenhandedly with our amazement at the occasionally undetectable proficiency of the machine, and with our relieved schadenfreude at its equally occasional parapraxes.

Läubli closed with what was, for me at least, his most reassuring, if provisional, conclusion: that the scope for using NMT to create allophone versions of poetry rather than prose was quite limited; indeed, that the only sensible lyrical application of AI at present was in creating versions of language games à la Oulipo, such as lipograms or palindromes, a contention that I have seen borne out, to my great if pusillanimous relief, by the doggerel produced on command by ChatGPT occasionally (in the strong sense of the word, as in on the occasion of a birthday or retirement). So for the moment, it seems, both poetical production and its translation are safely in human hands.

Nevertheless, I remained on my guard, and with the Senior College prompt in mind I sought advice for my discussion of an analogue practice in an increasingly digitalized world in some champions of the old ways. The first, which gave me my title—and which, I will admit, was chosen in part merely for its recognition value—is of course Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” and his proposal that artistic production is transformed as a practice when the parameters used to assess it are fundamentally altered. “But the instant the criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production,” Benjamin writes, in Harry Zohn’s translation, “the total function of art is reversed. Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice – politics.” Could Benjamin’s formulation, I wondered, be applied to the latest developments in artificial intelligence, as it is used to create texts, both “everyday” and para-literary, thus challenging the “authenticity” of literary creation, its ritual aura, its individual genius? And what indeed might be the “politics” of such a move? At another recent event at the Literaturhaus, the author and AI expert Patrick “Karpi” Karpiczenko raised the spectre of “good enough” writing, troubling to those who earn their living with the craft: “good enough” writing, said Karpi, is that species of text produced by AI that does not perhaps bear the idiosyncratic hallmarks of human creativity, but is at least fit for purpose. And thus gives rise to a reversal of the old warning, that the perfect is the enemy of the good.

But maybe we’re done with authenticity anyway, with the genuine work of art, with individual genius, with the aura. Benjamin himself, after all, seems to have been over it as soon as he enunciated the idea. For we have of course seen an exponential increase in the pace of reproduction since the interwar period. Ours is a veritable age of echoes, of doppelgangers, of re-creation, of challenges to authenticity; and all of these gestures were always already the hallmarks of the work of translation, and specifically the work of translating poetry. For if, as Robert Frost suggested, poetry is what is lost in translation, then translators of poetry are on a fool’s errand at best; and if Coleridge was right in his assessment, that poetry is “the best words in the best order,” then its translators are not only traitors, they are also grave robbers, iconoclasts, and vandals. (Just to give this mini-chrestomathy—Poetry Is, as it were, by Reader’s Digest—a little balance, I note that the poet Chaim Nachman Bialik said translation is like “kissing through a handkerchief”; while in a recent review of a novel by Jennifer Croft, herself a translator, the author remarks that translation “is always a threesome,” the primal scene viewed from the perspective of the parents, frustrated in flagrante by the interposition of an epigone interpreter. So translation is at least sexy, if also a criminal enterprise.)

Perhaps, to borrow Linda Hutcheon’s formulation, it would be more useful to call poetry in translation an “adaptation”: that is, repetition but not replication, thus forsaking neither its “Benjaminian aura” nor the pre-political “comfort of ritual”. Further, and continuing with the same theoretical model, we could stress both the processual and the productive aspects of the term “translation,” as Linda Hutcheon does with the term “adaptation”—its diachronic place in a long and continuous tradition, or as one element in a necessary chain of at least two texts; and its synchronic existence, at a given moment under particular historical conditions.

This is what I propose to do here: to give a sense of my own practice—or process—when I translate poetry, and to present some finished examples of my production that might more properly be termed adaptations, due to their migration not only between linguistic idioms, but also across generic and cultural borders.

But before I do, let me present a more sanguine illumination of my trade than that afforded by Frost, Coleridge, or Bialik, one that constitutes a metatextual staging of the creative act that is translation, one that is, as it were, a degree zero of translation, and which is, furthermore, only available in the translated version of its particular Ur-text, and thus enjoys a double guarantee—of authenticity, I would suggest, if we had not already placed that term under erasure.

In her 2018 version of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, Olga Tokarczuk’s 2009 eco-vegan whodunit, Antonia Lloyd-Jones, one of the Polish Nobel laureate’s two sterling English translators (the other is Jennifer Croft, as it happens)—Antonia Lloyd-Jones heroically resolves what must have seemed at first glance an intractable problem. The narrator of Tokarczuk’s novel, Janina, an elderly literary translator living in the Polish countryside, is engaged in a project with her friend and colleague Dizzy: the two are preparing Polish versions of the poetry of William Blake. In the scene in question, Janina and Dizzy have just begun their tandem work on “The Mental Traveller,” a poem unpublished during Blake’s lifetime, and collected in The Pickering Manuscript.

Tokarczuk writes (in Lloyd-Jones’s rendering): “right at the start [viz in the poem’s title, “The Mental Traveller”] a dispute arose [between Blake’s two Polish interpreters, Janina and Dizzy] over whether we should translate the English word ‘mental’ as mentalny—‘mental’ in the literal sense, meaning ‘of the mind’—or duchowy—more like ‘spiritual.’”

So far so good: Lloyd-Jones has faithfully conveyed a fairly standard point of philology, one furthermore that English scholars of Blake will themselves have wrestled with in their reading of the unadulterated text, given the poet’s penchant for idiosyncratic usage (think of “Mental Fight” in his celebrated “Jerusalem”).

At any rate, “The Mental Traveller” begins:

I travel’d through a Land of Men,

A Land of Men & Women too,

And heard & saw such dreadful things

As cold Earth wanderers never knew.

And the two fellow translators begin, side by side: “First, we each wrote out our own translation, in the trochaic meter more natural to Polish verse, then we compared them, and started to wind our ideas together. It was a bit like a game of logic, a complicated form of Scrabble.”

And then Lloyd-Jones goes on, admirably and incredibly, to render Tokarczuk’s fictional—or rather, actual—Polish translations of Blake’s English poetry back into English, three times (and then, later, a final fourth):

Over Human Lands I wandered,

Lands of Men and also Women,

Seeing, hearing things so fearful,

Such as no mind ever summoned.Or:

Through the World of Men I journeyed,

Realms of Men as well as Women,

Hearing, seeing sights so awful,

No pure soul would ever dream on.Or:

Throughout the World of Men I wandered,

Crossing Realms of Men and Women,

What I saw and heard was ghastly,

Such as None would ever dream on.

The two colleagues then discuss their versions, bringing to bear perspectives, both political and prosodic, with which Tokarczuk’s habitual readers will have become familiar:

“Why have we insisted on putting the word ‘women’ at the end?” I asked. “What if we made it: ‘Men’s and Women’s Land’? Then the rhyme would be with ‘land’. ‘Hand,’ or ‘stand,’ for instance.”

And here of course Lloyd-Jones has had to concoct alternative English rhymes to convey the Polish non-cognates. The text continues:

Dizzy said nothing, chewed his fingers and at last triumphantly suggested:

As I wandered human countries,

Men’s and women’s shared domain,

Dreadful things did I encounter,

Horrors none on Earth had seen.I didn’t like the word “domain” [notes Janina], but now we were up and running, and by ten o’clock the whole poem was done.

What Lloyd-Jones enacts here, effectively, in a hypertrophied Borgesian rewriting, or rather, making strange of the English refracted through the Polish and back into English, is an experimental proof of Proust’s contention that writing is translation; indeed, in a Derridean gesture of reversal, she gives us translation as prior to writing.

*

And with that I come, at last, to some samples of my own work as a translator of poetry. Now, although I cannot claim to have overturned the hierarchy of writing and translating in my practice, it is true that I first tried my hand at English versions of foreign verse not long after I had begun, with typically pubescent self-importance, staking my claim on lyric posterity.

One of my earliest attempts was a translation of a poem by Catullus, which I had read in a first-year seminar with Kenneth Quinn and which I have preserved and embellished since. My version takes extraordinary liberties with the Roman’s, liberties mainly of the formal variety, since I have transposed Catullus’s characteristic hendecasyllabic metre, unrhymed, as was the normal case with Latin verse until the Medieval period, into the Renaissance straitjacket of an Italian or Petrarchan sonnet (not entirely an alienation, given Petrarch’s admiration of his Roman Republican forebear). But the chief fun, for me, comes in an entirely paratextual element, the punning title I have given to Catullus’s otherwise merely numbered poem.

Catullus 13: More Scents than Money

You will dine well with me, Fabullus, friend,

Gods smiling on you, in a few short days —

Provided, large and sumptuous, you raise

A meal, to which a lovely maid append,

And wine and wit, and all your laughter lend.

These things, and others like, our friend in grace,

You’ll need to bring; and here’s the cause apace:

Your poet does his purse with cobwebs mend.But in return you will receive pure love,

Or rather, what’s more elegant and sweet:

For I shall give you perfume, which did those

Almighties grant my girl, from up above;

Which, when you smell it, you’ll those same entreat

To make of you, Fabullus: One. Great. Nose.

I moved on, eventually, as one does, from the frivolous and often randy Catullus to his younger contemporary Horace, whose career coincided with the rise of the Roman Empire and who produced among other things some joyful but high-minded expressions of Epicurean philosophy in verse form. Since I have remained less high-minded myself, however, and although I was at the time already older than Horace was at the time of his death, though not spiritually much past puberty, the poem of his that I chose to adapt was one of his amatory odes: or rather, his famously ironic prayer of thanks for his fortuitous release from a love affair with an unsuitable partner. Again, the fun for me comes with my sassy title, which plays on a stock classical expression as well as on the name of Horace’s ex-girlfriend; more than that, however, it is now less a formal change that I have rung than a generic, since my version, which has appeared in Ezra, a serious online journal of poetry in translation, was in fact originally intended to serve as the lyrics to a song, in the neo-disco idiom specifically, an ongoing project with a musician colleague: on which more in a moment.

Who’s loving you now, Hot Pants: what slender-hipped

Boy drenched in aftershave is making googly eyes

Outside the latest club?

Who’d you do your golden hair up for tonight

In that meticulously artless quiff?

Damn, but he’ll be cursing

Your faith and gasping goggle-eyed

As black winds whip the ocean wave

Engendered by a fickle deity!

He who now weighs your worth in bullion,

Who thinks you’ll always be available, always in the mood,

All ignorant of the fool’s gold

Under his hands.

The more fools they

Who’ll fall for anything that glitters! As for myself,

I’ve hung my dripping glad rags up to dry

As an offering to the Mighty God of Storms

And in sacred token of my thanks.

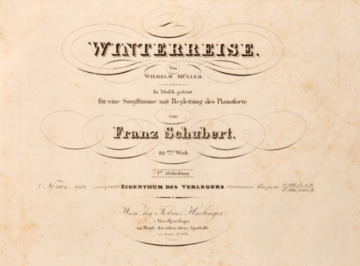

As to that musician colleague: my work as a translator of poetry has been importantly influenced by collaboration with musicians, in both pragmatic, professional terms and in matters of technique and theory. And apropos second puberty, during the first decade of the present millennium I served as lyrics writer and chief vocalist for The NewMen, a country-punk outfit based in Zurich and comprising a Rockabilly-inspired lead guitarist from Basel, a thrash-punk enthusiast bass player from Bern, a Dutch drummer with a passion for Prog Rock, and a Reggae-loving rhythm guitarist. (It goes without saying that we broke up, following the release of our second album, due to artistic differences.) Driven as much by a mischievous eclecticism as by the sheer need for sources, I adapted as lyrics for our two-minute toons and more soulful, though no less raunchy ballads texts such as “June,” a socially critical text by Shi Tao, the imprisoned Tiananmen Square dissident, whose elegy of lost innocence both amatory and political reminded me of Neil Young’s “Ohio,” and “Gute Nacht,” by Wilhelm Müller, the first in the Winterreise series famously set to music by Franz Schubert. I will return to the latter in a moment.

First, however, I want to say a word about a more recent, still ongoing musical collaboration, one in which my poetic translation plays a central and explicit role. Since 2015 I have been a member of an association known as Besuch der Lieder, or “singing visit,” which is a play on the title of Heinrich Heine’s first collection of poems, Buch der Lieder, or “book of songs,” published in 1827. Heine is, of course, among other things, the Jewish-born author of verses so well known and loved that not even the Nazis were entirely capable of expunging them all from the German canon; and his renown comes in large measure from the fact that eminent composers of the Romantic period, among them Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann, set his poems to some of the most beautiful music of the period, indeed of any period; songs which were then performed, during the nineteenth century, at private gatherings in the homes and at the salons of German and Austrian society.

True to its name, then, our association seeks to recreate this phenomenon, by staging private house concerts throughout Switzerland and in the countries it borders, typically featuring piano and one or two, occasionally three singers, performing programmes of Lieder, chansons, or canzone assembled from the classical repertoire: Schubert and Schumann, of course, but also Saint-Saëns, Strauss, and Ravel.

My role in the association is that of dramaturge, or impresario, guiding the small audiences of handpicked guests through our thematically linked selections, commenting, not on the music, but on the poetic texts chosen for the various settings. And in this capacity, I often find myself translating those texts—not into English, since our audiences are usually Germanophone, on occasion Francophone or, more rarely, Italophone—but typically from French or English into German, a direction that cannot concern us here today. In my work as a publicist for the association, however, I have found myself preparing translations in the opposite direction, from German into English; and on one such occasion, in fact, I was moved to create two versions of the text, by Franz von Schober (1796-1882), for one of Schubert’s most celebrated, most programmatic songs, “An die Musik” (D 547): one archaic, the other modern, to demonstrate our capacity for bridging the affective divide of two centuries.

To Music (A)

Full often hast thou, gracious art,

When savage life had caught me in its net,

A love within me stirred to warm my heart

And salvaged me from this world to a better yet,

From this world to a better yet!Oft hath a sweet and sacred chord of thine array,

A sigh, escaped from out thy harp to me,

And bared a heav’n of hope for better days:

Thou gracious art, for this my thanks to thee,

Thou gracious art, my thanks to thee!To Music (B)

How many times have I been low,

Caught in a day’s embrace,

And you were there to comfort me,

To warm my heart and transport me

off to a better place!How often has a song of yours,

a sigh, a sound rung out.

Sweet music, how you made me see

a better world awaited me:

my thanks to you for that!

In this same adaptive vein I am currently at work on a new offering for Besuch der Lieder, which has to date, for obvious reasons, focused on German-language evenings. I am preparing a programme specifically intended for an audience of Anglophones, of which there are surprisingly many, among the “expats” of Zurich and Geneva: my concept is that we perform Schumann’s Dichterliebe cycle, “A Poet’s Love,” his setting of a series of texts from Heine’s Buch der Lieder, in German, interrupted or punctuated by my performance, Cabaret-style, of my own new English adaptations of the poems in a variety of styles, archaicizing or modernized. Here is a sample of the latter sort, first in a standard translation, then in my revamped version.

I bear no grudge

I bear no grudge, though my heart is breaking,

O love forever lost! I bear no grudge.

However you gleam in diamond splendour,

No ray falls in the night of your heart.I’ve known that long. For I saw you in my dreams,

And saw the night within your heart,

And saw the serpent gnawing at your heart;

I saw, my love, how pitiful you are.

I bear no grudge.Tr. Richard Stokes

Me, hold a grudge?

Me, hold a grudge? Not even broken-hearted,

there’s no hard feelings, though we’ve truly parted!

No matter how you preen and strut your stuff,

and sport your flashest threads: your heart is dark enough,I’ve got you pegged.

Me, hold a grudge? Not even broken-hearted.

I saw you in a dream, you know,

and saw the night that fills your soul,

and saw the snake that feasts upon your heart,

I saw, my love, how miserable you are.

Me, hold a grudge?Tr. RN

As my final example, allow me to return to that earlier phase of my poetico-musical collaborations, to my work with The NewMen and to my adaptation of the song from the Winterreise to which I have referred, and which offered an unwitting foretaste of this current project and a bridge to my current, late phase of creation.

Schubert’s 1828 cycle was the setting of poems by the recently deceased author Wilhelm Müller. The 24 texts of Müller’s cycle render an impressionistic account of a solo voyage, made during the winter months by a first-person narrator away from a life of social connection and towards an uncertain, solitary, death-tinged destination. The writer of the poems, Müller, and the composer of the songs, Schubert, were both young men at the time of creation, both biologically and politically speaking: young in years as well as in the Oedipal sense of rebels against the “old” order, the restoration reactionism of the post-Napoleonic Biedermeier period, in which politics had been put on ice, and anything vaguely critical of the restored regime had to be expressed allegorically.

What is immediately salient in my version of the German text is that it plays fast and loose with (perhaps hackneyed) jokes and country-bumpkin idioms in a way that is foreign to Müller’s plain speech, while at the same time pushing the suicidal imagery of the German text rather farther in the direction of the literal: “There’ll be blood on the snow tonight,” after all, promises an act of violence that is all the realer for its harnessing as a figure for writing.

The music we developed as a setting for the text, meanwhile, substitutes rising vocal energy and melodic dynamics for Schubert’s ironic, counterintuitive shift, towards his song’s close, from minor to major. “Blood on the Snow Tonight” also mimics the plodding rhythm of “Gute Nacht” with a stumbling percussion break, which was regularly the source of hilarity in rehearsal when our drummer would attempt to change it up with a less awkward variation. The combined effect of these musico-structural gestures, then, was to give our song an air of defiance in the face of despair, one shared with the yodeling blues of the prolific Hank Williams, whom I am pleased to refer to, anachronistically, as the Schubert of country music.

Of course, these interpretations, both textual and, especially, musical, were not wholly deliberate, but grew in large part out of the collaborative effort of “jamming” in a Swiss bomb shelter. My bandmates and I were moved at the time by our double indebtedness to both Country and Punk idioms (Johnny Cash + The Clash): to a ferment of folk conservatism and urban anarchism that proved extraordinarily fertile; and it is largely in retrospect that I have become conscious of the degree to which we were reproducing what may very well have been the experience of a yet more ancient lyric tradition—or at least, of that oppressive period in which Schubert lived. Biedermeier was in some ways the mirror image of our own age, in which every utterance is explicitly suffused with politics; in other ways, of course, we are currently witnessing a distressing form of restoration, a revanchist backlash on the part of a series of anciens régimes, reports of whose death seem to have been greatly exaggerated.

*

So let me now, in conclusion and as promised, return to the political dimension of poetry, and thus of its translation. In “The Prevention of Literature,” an article published in 1946 in the journal Polemic, George Orwell writes about the relative neglect of verse by totalitarian regimes, which tend to focus on the perceived threat posed by writers of prose; his tacit suggestion is that poetry accommodates itself politically to fascism. “There is no such thing as genuinely non-political literature,” Orwell writes,

and least of all in an age like our own, when fears, hatreds, and loyalties of a directly political kind are near to the surface of everyone’s consciousness. Even a single taboo can have an all-round crippling effect upon the mind, because there is always the danger that any thought which is freely followed up may lead to the forbidden thought. It follows that the atmosphere of totalitarianism is deadly to any kind of prose writer, though a poet, at any rate a lyric poet, might possibly find it breathable.

And Orwell goes on:

It is not certain whether the effects of totalitarianism upon verse need be so deadly as its effects on prose. There is a whole series of converging reasons why it is somewhat easier for a poet than for a prose writer to feel at home in an authoritarian society. To begin with, bureaucrats and other ‘practical’ men usually despise the poet too deeply to be much interested in what he is saying. Secondly, what the poet is saying—that is, what his poem ‘means’ if translated into prose – is relatively unimportant even to himself.

Here Orwell is clearly thinking more of Vergil, pressed into service by Caesar Augustus as the glorifier of his imperial project, rather than of a contemporary of his own like W.H. Auden, a deeply political poet, the meaning of whose work was of profound importance, to himself and to his like-minded readers. (And by the way, as I learned reading the Aeneid years ago with the late Father Owen Lee, even Vergil managed to smuggle in a certain ambivalence about the Roman enterprise into his etiological pageant of the founding of the Eternal City.) At very least, Orwell here is displaying his own contempt for what he may, in 1946, have still viewed as the bourgeois formalism of poetry.

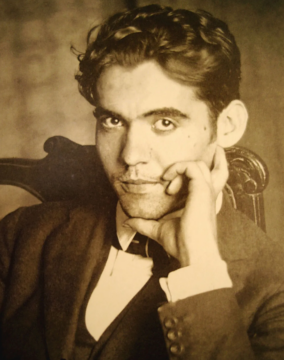

Because of course there are indeed poets who have not accommodated themselves to totalitarian regimes, and who have paid a high price for their intransigence. The jury is still out, I suppose, on Bertolt Brecht; but what of Mahmoud Darwish and Else Lasker-Schüler, variously attacked and repressed for their commitment in verse to a cause, or a people, or a language? And what of Federico García Lorca, murdered shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War?

In a recent essay in Paris Review, Zain Khalid writes about García Lorca’s time at Columbia University in 1929 and about the resulting, posthumously published volume, Poet in New York, in which the poet expresses his solidarity with a range of the city’s dispossessed and excoriates its savagery and corruption at the dawn of the Great Depression. About García Lorca’s death in 1936 at the hands of nationalists, Khalid says:

Though the exact circumstances surrounding his execution remain unknown, it was a civil war, the nationalists wanted a return to the monarchy, and he was a gay socialist; these things tend to happen.

In fact, it may even have been the case that García Lorca was murdered despite his by then celebrated verse, rather than because of it; the reasons for his targeting remain lost along with his remains. What is certain, and of particular interest to us, here, today, is the way that García Lorca’s legacy has been preserved in part through his translation—or rather, through his adaptation—in song. Leonard Cohen often remarked on the role that the Spanish poet played in his own growth as an artist; in his speech of thanks for the Prince Asturias Award in 2011, he said:

Now, you know of my deep association and confraternity with the poet Federico García Lorca. I could say that when I was a young man, an adolescent, and I hungered for a voice, I studied the English poets and I knew their work well, and I copied their styles, but I could not find a voice. It was only [when] I read, even in translation, the works of Lorca that I understood that there was a voice. It is not that I copied his voice; I would not dare. But he gave me permission to find a voice, to locate a voice; that is, to locate a self, a self that is not fixed, a self that struggles for its own existence.

Tellingly, Cohen speaks here of copying the styles of the English poets he studied, but of refraining from copying his Spanish idol. Instead, he says, García Lorca gave him a voice, even a self, and a political self at that, one that is unfixed and in struggle. (Recall the trial of the poet Cohen stages in his 1974 song, “A Singer Must Die”: “And all the ladies go moist and the judge has no choice / A singer must die for the lie in his voice.”) Accordingly, when Cohen explicitly uses a poem by García Lorca as the material for one of his songs—Cohen’s “Take This Waltz” is based on García Lorca’s “Pequeño vals vienés,” or “Little Viennese Waltz,” published posthumously in the Poeta en Nueva York volume—the Canadian singer does quite literally take the Spanish poet’s waltz and run with it, to produce a version that is in the very strongest sense an adaptation rather than a translation of the poem: since the latter, as we know, although it may well be quite sexy, is in fact a crime.

This text is a slightly altered version of a talk I gave, at the invitation of Magdalene Redekop, under the auspices of Senior College at the University of Toronto, on April 3, 2024. The full lecture can be viewed here.

The two NMT graphics underlying my first and last illustrations above are used courtesy of Samuel Läubli.