by Marie Snyder

Over thirty years ago I was in an on-again-off-again relationship that I just couldn’t shake. After months of different types of therapies, I lucked into a therapist who walked me through a version of the Gestalt exercise of talking to a chair, which ended my longing for this guy on a dime.

Over thirty years ago I was in an on-again-off-again relationship that I just couldn’t shake. After months of different types of therapies, I lucked into a therapist who walked me through a version of the Gestalt exercise of talking to a chair, which ended my longing for this guy on a dime.

The exercise had me reimagine many ways he had enraged me, bringing all that to the surface. Then it raised any guilt I had around my own actions towards him, sadness around missing him, and finally ended with celebrating what I learned from him. It took just an hour, and I left feeling completely finished, excised of any clinging or craving, and able to effortlessly say “No thanks!” to his next late-night phone calls. Pairing words and actions with emotions in a contained and structured time and space, that gives some order to the chaos, might do next to nothing — but it might help to move through a difficult transition. I was so impressed with this power hour that I went to grad school to study ritual work. Gestalt psychotherapy is a far cry from cultural anthropology, but I perceived a connection to rites of passage that help neophytes transition from one state to another.

I recognize the cringe-factor in all of this, but it’s worked for thousands of years to take children into adulthood, and we’ve kept at it when marrying and burying, so there’s likely something useful in the process. And it feels like we need something transformative more than ever.

In his Collected Works, volume 9, almost a full century ago, Carl Jung wrote,

“We’re ritually and symbolically impoverished: I am convinced that the growing impoverishment of symbols has a meaning. It is a development that has an inner consistency. Everything that we have not thought about, and that has therefore been deprived of a meaningful connection with our developing consciousness, has got lost. If we now try to cover our nakedness with the gorgeous trappings of the East, as the theosophists do, we would be playing our own history false . . . . What is worse, the vacuum gets filled with absurd political and social ideas, which one and all are distinguished by their spiritual bleakness.”

Over the years, as we’ve become more secular, we seem to have lost the ability to sufficiently mark turning points in our lives, times of crisis and opportunity that help us to reconstruct ourselves. Instead, we stay stuck in old behaviours long after they’ve lost their efficacy. We’re pretty good at ceremonies around hatching, matching, and dispatching, but there are many points in life that call for a poignant shift in thinking and being.

Years later, I used the general format of a rite to teach classes an exercise they could try to help them navigate the transition away from home or when they bump up to strong feelings that might be called a quarter-life crisis. More profoundly, at some point between 20 and 35 life can catch up to us, and we might start to question what we’re doing with our lives as nagging regrets start to seep in. Many start to realize their own mortality and the limitations of their own capabilities, clarifying the inability to accomplish all they long to pursue. That discomfort could be a signal that more attention needs to be paid to this moment of transition. Many struggle to step into adulthood. Part of that may be from straddling the line between child and adult in a culture that sees adults as stagnant, rigid, and boring. Many want what de Beauvoir calls a childish freedom that is devoid of responsibility, but that misses the radical freedom that comes when we recognize that our agency is inextricably tied to accepting our role in events.

Most of us do little rituals all the time to help us through transitions: buying new pens and binders (or flash drives) at the start of each semester of school even if we don’t really need them just to kickstart the new term, or always making it for Sunday dinner even if we don’t love the food. Or we might insist on a specific kind of birthday cake each year even though it’s not even our favourite anymore. The action is more than a means to an end. Something else is going on. A rite is not necessarily a religious exercise, and it’s definitely not a tradition for those of us so far removed from anything like it, but it can be a way to bring up emotions around a transition in order to help look to the future with new eyes. Change is hard, and every little bit can help get us through an upheaval.

Prep Work:

Cultivating a rite of passage can help get us over the hump of a major transition by helping us grieve the old and embrace the new. It’s a three-part play, but first we have to figure out the props and events that can provoke a transformation. It can take some thought to find things symbolic of the old and new despite being a straightforward concept. For weddings, we have a stag and doe to say goodbye to our single selves, and rings and a new name to mark the change. For burgeoning adults, it could be photos or a stuffed animal or other toys that are an important connection to the past and an apartment key or tattoo that signals the event. Objects that carry meaning to us have a story behind them and a feeling attached to them. They can’t be borrowed from other cultures to work.

The really hard part is figuring out what has to happen to get to the other side and then how to provoke those behaviours. What does it look like to be an adult? It’s surprisingly difficult to create a clear list of characteristics, so it can help to think of the opposite of childish traits. My students have come up with things like being responsible (step up to apologize and fix mistakes), independent (clean up after self and make a living), be in control of emotions in public (no flipping out), be other-centered (care about how your words/action affect others), persevere in tasks, be able to ask for help and offer help (interdependence), and be willing to play and be silly too at appropriate times.

Brainstorming ways to provoke these behaviours is the most creative part of the exercise. It takes a lot of thinking and figuring to match desired characteristics to activities that are the perfect level of challenge for the participant. In some ancient cultures, they practiced tolerating adversity without complaint by standing for hours covered in fire ants, but we might just sit in long tickley grass or an uncomfortable chair. Practising responsibility might look like writing letters of apology to anyone harmed in the past. To develop interdependence we might offer to do all the housework for a week, and recognize when we need help to finish before we get irritable. We might volunteer to help people. We might give up our continuous entertainment to get back our capacity to think and create. It can take weeks to come up with the just-right objects and actions for an event that might just last an hour or a weekend.

The Three Acts:

Separate from regular society and activity in some way:a new location or even your living room done up differently. Flowers and fire (candles) are both transformational symbols often used in rituals for more than just prettying up the place! Wearing different clothes and/or getting dressed differently which might include special cleansing or fasting, with more attention, is important to wake up your amygdala by letting it know something really novel is happening here so it will pay attention. Then separate from your former self with a symbolic death, which could involve letting go of the object representing the old version through burning or burying (in the ground or in the back of a drawer). Older traditions might amputate a finger or knock out a tooth, but cutting a lock of hair could also suffice. A gentler version of events can be as powerful.

Transformation is the liminal period – the threshold between before and after. It incorporates the activities that hope to provoke the new behaviours through a physical and cognitive exercise, which, if suitably challenging, can tire the inhibitory capacity of the prefrontal cortex and let emotional elements come to the forefront. This stage can also include singing, chanting, dancing, walking or avoiding sleep for extended periods to help change the physiology. In a group, affinity comes through shared difficulty, which is why initiations work in frats; chanting words can prevent clear individual thought. Rites are a tool that can be used for personal transformation as well as group conformity for good or evil. Used ethically, they can help to practice the characteristics of the other side, sitting uncomfortably without whinging to challenge our self-control or scrubbing gunk out the back of mum’s fridge to refine our other-centeredness.

Incorporation typically involves joining back with a society that recognizes the new identity, which is a barrier for individual rites, particularly if even close friends and families aren’t aware of the attempt at transformation. Being treated like a little kid can reinforce child-like behaviours and make it more difficult for the event to stick. However, when I yelled and cried to an empty chair as I struggled to end a disastrous relationship, I was amazed at the switch that flipped in my head. This is a place for celebrating the new with a feast of special foods and something new to mark the change: like a new clothes, a tattoo, or a new name.

Additional Considerations:

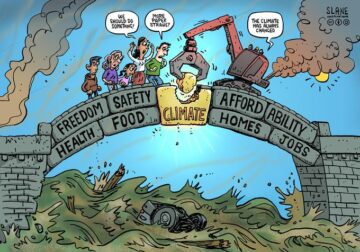

These exercises are for individuals or groups, but it feels like we need something more universal in these times. With climate change, it seems like we’re living so much nearer to death and struck with a sense of dread in the background of all we do, if not straight up grieving in advance. Some climate scientists believe it’s not possible for large mammals like us to make it into the next century without dramatic and immediate action, and that’s not happening. Some insurance companies are no longer covering homes in certain areas. You know it’s real when financial institutions start taking action.

The inevitability of ecological collapse before the end of the natural lifespan of some children alive today, and the abandonment by adults in power who are meant to protect them, might require a more community-based effort at transitioning. We have always needed to come to terms with our own demise, but now we need to register the fruitlessness of “leave behinds” – anything crafted in hopes they live on long after we’re gone. Who will be there to see them??

It’s a special challenge to be worried for all of humanity and for all the larger mammals that we’re likely to take with us. I wonder about the possibility of a transformation into a humanity that strives to eat low on the food chain, waste as little as possible, resourcefully reuse the most menial items, and enjoy life close to home. It’s the kind of life my parents lived, yet it feels completely alien and so impossible to reach. And, unlike talking to a chair to ditch a dying romance, we just don’t want to change enough to save our species.