by Peter Wells

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’

Our classes in the British university where I was teaching Pre-sessional students (mainly Chinese) were cancelled for a Special Event. Instead of their normal lessons on academic English, our students were shepherded off to witness a series of presentations on ‘learning.’ Learning, they were told, was ‘Collaborative,’ ‘Creative,’ and ‘Self-directed,’ and depended upon ‘Taking Responsibility for one’s own learning,’ ‘Thinking Critically,’ ‘Problem-solving’ and ‘Taking the Initiative.’

While no one would dispute that these approaches are valuable in themselves, and relevant in some learning situations, they clearly exemplify stereotypical Western liberal values. I looked in vain in the prospectus that had drawn my students to attend our university for evidence that the syllabus included the imparting of these ideals. No, what they had paid for was instruction in the English language; specifically, training in academic writing.

To me this looked like a failure on our part to supply our customers with the goods they had paid for. More seriously, it looked like a neo-colonialist attempt to impose British cultural values upon a captive audience of rather vulnerable foreigners. I do not think that our lecturers, if they attended a conference in Beijing, would appreciate being obliged to attend a plenary session on Chinese Communism. I observed as much to a senior lecturer, in the politest possible manner.

His response was robust. Apparently, learning can take place only with the sort of educational approaches that have developed in our culture over the past generation or so. My suggestion that Chinese people seemed to be very good at learning things – better in some areas than Westerners – was met with a direct contradiction. Chinese people could not really learn at all. Nor, it turned out, as the conversation developed, could Indians, Arabs or Africans. They were not even able to think properly. In fact, only Western people could think, or learn anything worthwhile, the qualification being softened to include people of colour who were entirely Westernised, like, say, Barack Obama. To be fair, the bit about Obama was an inference on my part. Read more »

I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson.

I began taking piano lessons when I was 8 years old, along with Lynn, my older and Mark, one of my brothers. Every Wednesday we’d walk together from school to a small storefront on Milwaukee Avenue about a half mile away. The store windows were covered in drapes, with a little sign indicating the teacher’s name and PIANO LESSONS. My sister gave her the $3 for three lessons, and we entered the small studio, which had a grand piano and a sofa, bookshelves, and a heavy, dusty drape separating the studio from the living quarters. We’d each wait patiently, doing our homework on the sofa while the other one had his or her lesson. We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.

We enjoyed learning the piano, but didn’t enjoy Mrs. K. She was creepy. We thought she might have been a Roma fortune teller or a magician, as she wore strange jewelry and shawls, and had Persian carpets and draperies around her studio. To us kids she looked about 90 years old (probably more like 40). She was actually a rather unsuccessful concert pianist, and memorabilia was scattered around the studio such as notices of performances and autographed pictures of famous conductors. She didn’t talk about it much her past life at all, as she was reduced to teaching piano lessons to the blue-collar neighborhood kids like ourselves. We persisted with lessons because we always did as we were told. We went home and put in our half-hour of practice on the second-hand but well-tuned piano that dad bought for us, and little by little we began to learn how to play.  America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

America is a truck rolling down a hill towards a cliff. The downhill slope is the erosion of democratic norms; the cliff is the point where anti-democratic forces become powerful enough to crush democratic opposition by authoritarian means. The re-election of Donald Trump would very likely see the country sail over that cliff.

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

Actress Cameron Diaz and her business partner, the entrepreneur Katherine Power, have been all over various media promoting

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a

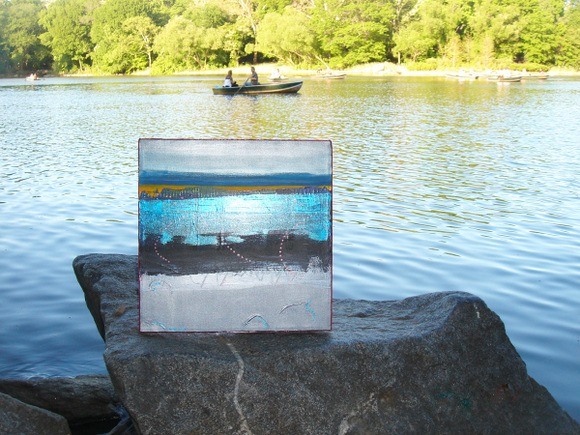

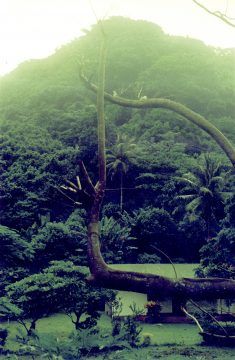

On November 11, 2019, I wrote a  In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.

In 1997, I was living on Ambae, a tiny, tropical island in the western South Pacific. Rugged, jungle-draped, steamy, volcanic Ambae belongs to Vanuatu, an archipelago nation stretching some 540 miles roughly between Fiji and Papua New Guinea. There, under corrugated tin roofs, in the cinderblock classrooms of a small, residential school, I taught science to middle- and high-schoolers as a Peace Corps volunteer.