Cat in the Domplatz in Brixen, South Tyrol, in June of 2015.

The ‘beauty of sorrow’ in the TV masterpiece, My Mister

by Brooks Riley

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

Being Korean is a behavioral science all its own. There are formalities at all levels of society and potential affronts lurking in every social engagement. Ageism is set in stone, and in honorifics that define older or younger persons, friends, siblings and relatives, as well as differing levels of social standing. Personal humiliations are many and varied, some of them universally recognizable, some of them exclusive to Korea’s tight-knit family structures or evident hierarchies. It goes beyond how to address someone: How to drink soju, how to pour it for a superior, how to bow, when to bow, who to bow to, when to get down on your knees—the list goes on.

This is why the title of the magnificent Studio Dragon series My Mister is unable to quite capture the honorific implications of Ahjussi, a man who is one’s elder by at least 20 years, who may or may not be your uncle. No matter. Part of the pleasure of watching this Netflix series is marveling at the many ways that behavior is stratified without harming the spontaneity and pleasures of social interaction.

If there’s a double helix running through the Korean psyche, then it consists of two strands, han (한) and jeong (정) two concepts that seem to infuse Koreans with states of mind that their dark history of multiple occupations has delivered right to their genes. Read more »

American Dirt and the Complicated Question of Testimony

by Katie Poore

Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico.

Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt is a string pulled so tightly it is on the verge, always, of snapping. It is like this from the first sentence, when our protagonist Lydia Quixano Alvarez’s 8-year-old son, Luca, finds himself in a rain of bullets while he uses the bathroom. By the second page, sixteen members of Lydia and Luca’s family are dead, murdered by the reigning drug cartel of Acapulco, Mexico.

I found American Dirt gripping, unrelentingly so. Every fifty pages I had to stop, breathe, do something else. It isn’t a book I could devour, mostly because I couldn’t stomach some of the endless grief it contained for more than an hour or two at a time. It felt grueling, and riveting, and so utterly foreign.

But American Dirt has, since before its release in January, been the subject of controversy and scrutiny, precisely because it is so utterly foreign, and because Cummins could not and has not undergone the traumas and trials of her protagonists. Cummins’ publisher, Flatiron Books, canceled her book tour due to the backlash. Read more »

On Light

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning. Read more »

The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning. Read more »

Visual Histories: Sara VanDer Beek

by Timothy Don

The current economic crisis is crushing artists, museums, and galleries everywhere. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, an exorbitant rental market made maintaining a practice difficult before this crisis hit. It’s even harder now. With 3QD’s permission, I’m going to use this column to talk about the work of some of the artists and art professionals I have met in the Bay Area. I ask you to support artists wherever you find them and however you can.

Roman Women XIII, by Sara VanDerBeek, 2013. Digital c-print, 66 x 47 3/4 in. From the series Roman Women.

A digitally manipulated and synthetically colored contemporary photograph of a sculptural object from classical-era Rome, this piece looks at first glance like a picture postcard, memento of a delightful afternoon spent at the Vatican museum. Look more closely, however: in subject matter and method, the work addresses and bridges in one stroke both the ancient world and our present moment. It projects the textures and patinas of the past onto the flat screens of the present, and it resituates that present as a way station on the journey through time of images and ideas, meanings and ideologies. It is both art and artifact.

We have become accustomed over the last several hundred years to an image of antiquity hewn from white marble: clean, harmonious, and transcendent; conceptually pure, flawlessly executed. In a word: Classical. Recent historical research, however, suggests that Roman statuary, along with the Greek originals that it copied, was polychromatic, embellished, and almost luridly vibrant. Sara VanDer Beek recalls this aspect of classical art by saturating her photograph with a shade of violet approaching Tyrian purple. She reminds us that classical doesn’t mean white. Classical was colorful.

Her aim, however, is not merely to introduce visual facticity to the historical record. This is a photograph of a copy of a lost original. It is the top layer in a stack of reproducible objects, evidence of the layering effect of and through which history is composed. This picture is then-and-now, uniquely contemporary in its utilization of present-day technologies of representation, archival in its reinscription of that technology within a geneology of visual representation dating back to the birth of western civilization. This piece accomplishes the same movement (from past to present and back again) with regard to its subject matter: the human female form. Read more »

Monday, July 6, 2020

Brains, computation and thermodynamics: A view from the future?

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Progress in science often happens when two or more fields productively meet. Astrophysics got a huge boost when the tools of radio and radar met the age-old science of astronomy. From this fruitful marriage came things like the discovery of the radiation from the big bang. Another example was the union of biology with chemistry and quantum mechanics that gave rise to molecular biology. There is little doubt that some of the most important future discoveries in science in the future will similarly arise from the accidental fusion of multiple disciplines.

One such fusion sits on the horizon, largely underappreciated and unseen by the public. It is the fusion between physics, computer science and biology. More specifically, this fusion will likely see its greatest manifestation in the interplay between information theory, thermodynamics and neuroscience. My prediction is that this fusion will be every bit as important as any potential fusion of general relativity with quantum theory, and at least as important as the development of molecular biology in the mid 20th century. I also believe that this development will likely happen during my own lifetime.

The roots of this predicted marriage go back to 1867. In that year the great Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell proposed a thought experiment that was later called ‘Maxwell’s Demon’. Maxwell’s Demon was purportedly a way to defy the second law of thermodynamics that had been proposed a few years earlier. The second law of thermodynamics is one of the fundamental laws governing everything in the universe, from the birth of stars to the birth of babies. It basically states that left to itself, an isolated system will tend to go from a state of order to one of disorder. A good example is how a bottle of perfume wafts throughout a room with time. This order and disorder was quantified by a quantity called entropy. Read more »

Google It! The Internet and the Nature of Knowing

by Ali Minai

“I’ll just google it again”, said my daughter when I asked her to remember something. It was a very reasonable suggestion, but it led me down an interesting line of thought about the nature of knowing and its recent transformation. Much has been said and written about how the Internet has changed human knowledge, in both positive and negative ways. The positives are obvious. The magic of the Internet, the World-Wide Web, and utilities such as Google and Wikipedia, have put enormous knowledge at our disposal. Now any teenager with a smartphone has effortless access to far more information than the greatest minds of a century ago. Even more importantly, the Internet has opened up vast new possibilities of learning from others, and allowed people to share ideas in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Not surprisingly, all this has led to a great flowering of knowledge and creativity – though, unfortunately, not without an equally great multiplication of error and confusion.

“I’ll just google it again”, said my daughter when I asked her to remember something. It was a very reasonable suggestion, but it led me down an interesting line of thought about the nature of knowing and its recent transformation. Much has been said and written about how the Internet has changed human knowledge, in both positive and negative ways. The positives are obvious. The magic of the Internet, the World-Wide Web, and utilities such as Google and Wikipedia, have put enormous knowledge at our disposal. Now any teenager with a smartphone has effortless access to far more information than the greatest minds of a century ago. Even more importantly, the Internet has opened up vast new possibilities of learning from others, and allowed people to share ideas in ways that were unimaginable until recently. Not surprisingly, all this has led to a great flowering of knowledge and creativity – though, unfortunately, not without an equally great multiplication of error and confusion.

In terms of negative consequences, perhaps the most widely explored idea is that of epistemic bubbles – closed informational ecosystems enabled by social media connecting largely like-minded individuals. With little external input and minimal internal dissent, people in such bubbles can quickly fall prey to outlandish beliefs without the possibility of correction. The hazard of epistemic bubbles is compounded by the Internet’s facilitation of false information – fake news, so to speak. Of course, neither epistemic bubbles nor false information is new, but the Internet has supercharged both by lowering the barriers to entry so far that random TikTok personalities and Twitter ideologues can have a degree of influence that was previously reserved for a small, better-informed elite. On the positive side, this democratization of information has broken through the systematic indoctrination that elites have imposed on societies throughout history. At the same time, it has also led to an unprecedented undermining of facts and the disintegration of a shared experience of reality. But my concern in this article is with a more subtle, well-known – but perhaps insufficiently understood – effect of the Internet on human knowing: The externalization of knowledge and its consequences for creative thought. Read more »

Yes, Another Essay on AI

by Fabio Tollon

You’ve heard about AI. Either it’s coming for your job (automation), your partner (sex robots), or your internet history (targeted adverts). Each of the aforementioned represent very serious threats (or improvements, depending on your predilections) to the economy, romantic relationships, and the nature of privacy and consent respectively. But what exactly is Artificial Intelligence? The “artificial” part seems self-explanatory: entities are artificial in the sense that they are manufactured by humans out of pre-existing materials. But what about the so-called “intelligence” of these systems?

Our own intelligence has been an object of inquiry for human beings for thousands of years, as we have been attempting to figure out how a collection of bits of matter in motion (ourselves) can perceive, predict, manipulate and understand the world around us. Artificial Intelligence, as eloquently surmised by Keith Frankish and William Ramsey, is

“a cross-disciplinary approach to understanding, modeling, and replicating intelligence and cognitive processes by invoking various computational, mathematical, logical, mechanical, and even biological principles and devices.”

AI attempts not just to understand intelligent systems, but also to build and design them. Interestingly enough, it may be the case that we could in fact design and build an “intelligent” system without understanding the nature of intelligence at all. Important to keep in mind here is the distinction between narrow (or domain specific) and broad (or general) AI. Narrow AI are systems that are optimized for performing one specific task, whereas broad AI systems aim at replicating (and surpassing) many (if not all) capacities associated with human intelligence. Read more »

Monday Poem

“Time is a static in the mind.”—Malachi Black, poet

Timesea

In the days when there were bona fide summers

when months were loyal to the expected,

when they stayed more or less within their lanes,

December not copping the joys of July, for instance,

when seasons honored tradition and did not

insist on mukluks in June or ban January snow,

time (though always mercurial) made sense,

or at least we’d trimmed its arrogant sails

whose masts and spars, like antennae,

we trained to troll timesea for wind steady enough

to give clear chronometric reception —something to rely upon.

But time has always ebbed and flowed like tides, it fell

and rose random as waves, so we concocted clocks

to lock time’s fundamental pace, the regularity of its sine.

But time is simultaneously as un-pin-downable

as background noise, a universally evasive

static in the mind

.

Jim Culleny

7/4/20

How Black Lives Matter Is Teaching Us To See Systemic Problems Again

by N. Gabriel Martin

Perhaps there is no greater testament to the triumph of individualism than the pro-gun slogan “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.” It takes an extremely narrow conception of responsibility to deny that lax gun laws are to blame for high rates of gun violence, but that view is pervasive anyway. Now, however, the Black Lives Matter movement is drawing broad popular attention to the fundamentally systemic character of racism, and giving us an opportunity to overthrow individualism.

Individualism stands in the way of serious public debate about many of our most serious social and political problems—from gun control to the erosion of public infrastructure and the racial wealth gap. That’s because it makes the onerous demand that in order to identify a problem, you’ve also got to find out who is responsible. F. A. Hayek, one of the principle architects of this ideology, put it like this: “Since only situations which have been created by human will can be called just or unjust, the particulars of a spontaneous order cannot be just or unjust: if it is not the intended or foreseen result of somebody’s action… this cannot be called just or unjust.”[i]

According to Hayek, complaining about a circumstance for which no one is entirely to blame is like complaining about the weather. It isn’t enough to point to some inequality, such as the gender pay gap, to recognise it as a social problem that we should try to correct. We can identify it as a fact, but in order to see that it is a problem, you have to find a culprit. Otherwise, doing something that alters it would actually be unjust (it might take money away from men, or take autonomy away from corporations).

The result is that we can prosecute the person who pulled the trigger, after they have already killed, but we’re powerless to do anything to stop the next gunman. Read more »

Protective Living Communities

by Charlie Huenemann

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

By 2025, protective living communities (PLCs) had started to form. The earliest PLCs, such as New Promise and New New Babylon, based themselves on rationalist doctrines: decisions informed by best available science, and either utilitarian ethics or Rawlsian principles of justice (principally, respect for individual autonomy and a concern to improve the lives of those most disadvantaged). Membership in these communities was exclusive and tightly guarded, and they had the advantage of the relatively higher levels of wealth controlled by their members.

One such community, New Promise, began as a complex of buildings 60 miles outside of Moab, Utah. These buildings included living accommodations, a central meeting hall/library/theater, a food market, a health care station, and a network of gardens and walking trails, along with infrastructure buildings such as a water reclamation plant and a solar power station. Nearly all of its residents are able to work from home. Visitors are allowed only after a medical screening, and new members are admitted only after a rigorous screening process. Community dues are set at one-third of income, and the community is managed by a board of seven elected officials. There are two recorded instances of families being evicted from the original New Promise, in each case because, in the view of the governing board, they were not willing to abide by the decisions of the community.

New Promise offers a high standard of living and a buffer against both disease and political instability. In exchange, the community requires individuals to subordinate their own interests to those of the community. Applicants with strong religious or political ideologies are not admitted. Its members are typically highly-educated workers in technology, education, or business. “In New Promise you are free to do as you please,” said one member, “so long as what you’re doing doesn’t make anyone else miserable.” Read more »

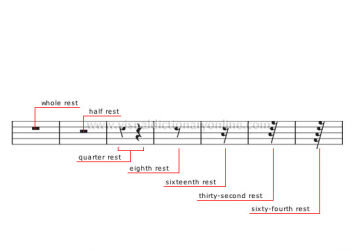

Rest

by Joan Harvey

Let’s face it, I’m tired. A phrase completely knotted up in the rather damaged circuitry that is my brain with Madeline Kahn in Blazing Saddles who managed to out-Dietrich Dietrich while being her own amazing self (if you haven’t watched this in at least the past few days you probably should). But, for better or worse, unlike Kahn, my tiredness is not from thousands of lovers coming and going and going and coming and always too soon.

But I digress. Tiredness is a digression from normal life. Repeated rounds of tiredness have been one of the leftovers people have reported experiencing from Covid-19, and, as I looked into it, from other viruses as well. I doubt I had Covid-19, but I did get very ill after flying back from NYC in late January and I’ve been struggling with recovery ever since. The tricky thing, the thing that really sucks, is that whereas with most bouts of tiredness one can recover relatively quickly and start normal physical activity, with this post-viral business, even tiny amounts of exercise can deplete one so much that only days of total rest really help. And, though I have past experience with this, I’m still not particularly well trained for it. The bigger problem, for me as well as others with this type of fatigue, is that one can feel fine during exercise, and then afterward become, as I have been, completely exhausted and shaky for days. As a pamphlet describing post-viral fatigue puts it, “Doing too much on a good day will often lead to an exacerbation of fatigue and any other symptoms the following day. This characteristic delay in symptom exacerbation is known as post-exertional malaise (PEM).” Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Fear in the Time of Pandemics and Terrorism

by Callum Watts

I worry. Asking someone out, speaking in public, stepping onto a flight, for me these mundane moments percolate with anxiety. These are personal fears, inner battles of no real relevance to the wider world and disconnected from any broader social meaning. Over the past couple of years though, I have had two experiences of fear that were both personal and political. I was caught in a terrorist attack and was struck down with covid-19 during the global pandemic. In each case the fear of death echoed bone deep within me, and in each case that fear reverberated through the body politic and society. What interests me is the political aims for which that fear can be harnessed and the authenticity of the use of that fear. I don’t believe that we should be stoking fear for political ends, but we cannot escape the fact that our fears are already in the political arena, and so we must learn to live with them.

Picture a warm summer night in London’s bustling Borough Market. I’m enjoying one of those endless evenings of conversation, eating and drinking with my family. My sister has just left early to meet some friends, when all of a sudden running, scuffling and shouting can be heard. It’s difficult to explain why, but a certain franticness in the movement and a strident tone to the shouts make my blood run cold. My whole body freezes and a tension forms in my chest, like a knot being pulled tight. Then as screams and shouts mingle with gun fire and things smashing, the knot dissolves as adrenaline courses through me. I’m alert, focussed, prepared to take control and spring into action. Months later, that initial stab of fear would still occasionally manifeste and get my adrenaline pumping. This could be triggered by being in a public space or on public transport, a loud noise, or by the memory of someone bleeding out on the floor. These fears were mine, yet they quickly became absorbed into a wider debate. Read more »

Reality Has Left The Building

by Thomas O’Dwyer

Our world (made of atoms) is crammed with paradoxes. Particles act like waves, waves like particles And your cat can be dead and alive at the same time. Just step through your looking glass and welcome to the quantum world. “If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you haven’t understood quantum mechanics,” the physicist Richard Feynman once said. Of course, the non-scientific reader may respond, “Why would I want to understand it?” If a genius like Feynman became lost in the twisting labyrinth of the quantum world, abandon hope all ye who expect to become enlightened here.

Quantum theory is famously opaque, and it drew dismissive grumbles from Albert Einstein. He was one of many superior minds who worried that science was abandoning its high road of rigorous clarity to dabble again in the murkiness of faith and superstition by even pondering the notion of quantum reality. Alive-dead animals, parallel universes, the existence of all times past present and future? These were for April 1 spoofs, right guys? Yet, whether one is aware of it or not, quantum mechanics has given us lasers, smartphones and many esoteric electronic components, like tunnelling diodes, from which we build our devices. They come with a weird label that says, we made them, and they work, but we don’t quite know how. Quantum computers will soon solve problems well beyond the reach of present-day digital machines – complex chemical analyses, dynamic biological processes. These will be of use to the pharmaceutical industries, and they will also model complex systems like financial transactions and climate changes. Read more »

Poem

Mother Writes to the ‘Lion of Kashmir,’ Long Deceased

February 2020

Dear Sheikh Sahib,

They tell me,

you are buried on the left bank of Naseem lake with views

of Hazratbal shrine, your tomb guarded by India’s troops.

I tell them,

this represents one of those paradoxes’ history keeps throwing

up: the same people who jailed you for many years now guard

your tomb and the same people whose ‘Lion’ you were are un-

happy with you for throwing their lot with the illiberal Pandit

Nehru who strung up Kashmir on the flagpole of secularism.

The world approved, but for decades the Congress Party

did to Kashmir by night what today the BJP is doing by light.

Sheikh Sahib, in your heart of hearts, you must have known

that we the Muslims of Kashmir struck at the core of Hindu

nationalist idea of Akhand Bharat, united, undivided India

from Afghanistan to Myanmar Thailand Cambodia and Laos. Read more »

The Avenue and the Magnifying Glass

by Joshua Wilbur

There are times when I can’t look away from The Avenue at Middelharnis.

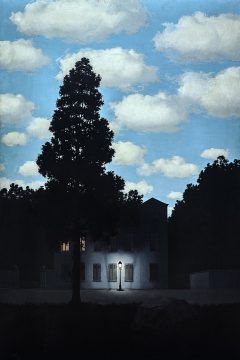

Completed in 1689 by the Dutch Golden Age artist Meindert Hobbema, the painting has entranced viewers for centuries. The English landscapists of the Romantic period admired and emulated its unusual composition. A young Van Gogh saw The Avenue in London’s National Gallery in 1884. “Look out for the Hobbema,” he would later write in a letter to his brother Theo. René Magritte allegedly produced forgeries of Hobbema’s paintings, and his Empire of Light seems to me a surreal reinterpretation of the Dutch master’s masterwork.

I say that I can’t look away from the painting because I set it as my computer’s background a few months ago. Artsy, I know. I see The Avenue a few times a day, usually in browser-obscured flashes. Sometimes I’ll push everything aside and just space out into it.

The painting is a great example of an “open” work of art. As described by Umberto Eco, open works encourage multiple interpretations and respond to the viewer’s evershifting historical situation, stage in life, or mood. If closed creations communicate one thing, open works communicate many things. They meet us where we are. I should say something about where I am and where we are before going further down The Avenue. Read more »

Spectacular Consumption: Revisiting the Society of the Spectacle

by Mindy Clegg

In our modern society, we are awash in a near constant barrage of information. It can be difficult for even the most critically-minded among us to sift through all of that information and vet it for truthfulness. It’s likely that we all are subject to some misinformation that we believe in the course of our daily engagement with mass media. Although it’s more pervasive and immediate in today’s interconnected world, this state of affairs has existed since the beginning of the industrial age, starting with publishing in the nineteenth century and then onto broadcasting media of the twentieth century. But, if the medium is the message as Marshall McLuhan argued, what do these generations of engagement with mass forms of broadcasting actually mean for us as a society? The content fades away into the background to some degree while the medium shapes our shared experiences. Broadcasting and social media have become a shared prism on world, with differing interpretations of events experienced in a similar way.

We rarely have public discussions on what a mass mediated society means for us, taking its existence for granted. Perhaps turning to a classic treatment of mass society might remind us of the historical and social constructedness of mass media. One such compelling work was the 1967 work by Situationist Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (published in English in 1970). Debord’s work has become a classic among philosophers, disaffected youth, and scholars attempting to come to grips with the role mass media plays in modern life. In this essay, I will argue that some of Debord’s assertions, such as his claim about the passivity encouraged by the spectacular industries, are incomplete. No form of mass medium was ever accepted passively. Rather, people as consumers often actively engaged with mass media, even if the goal was passive acceptance from the top down. I use the example of popular music to illustrate the point. Read more »

Monday Photo

This alpine meadow near my house went through yellow, purple, and white phases before finally blooming with all three colors simultaneously in a “second wave” now. It probably does this every year but I had not noticed until the coronavirus lockdown got me into the habit of walking by this area daily for some exercise and I started paying closer attention to my surroundings.

Acquiring A Taste For Ashes

by Mike O’Brien

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

It’s a bountiful feast for discriminating worriers like myself. Every day brings a tantalizing re-ordering of fears and dangers; the mutation of reliable sources of doom, the emergence of new wild-card contenders. Like an improbably long-lived heroin addict, the solution is not to stop. That’s no longer an option, if it ever was. It is, instead, to master and manage my obsessive consumption of hope-crushing information. I must become the Keith Richards of apocalyptic depression, perfecting the method and the dose.

Structure is important. Historical time-frames help. Covid is bad, and current, and a direct threat to me, but a once-a-century pandemic arriving right on time shouldn’t disrupt my worrying on a macro level. I’ve budgeted acute anxiety for just this kind of thing.

The protests in the US are full of promise, both for good and for ill, but the systemic problems whence they sprung are old news. The uprising should have happened decades ago. They may happen again, for the same reasons, decades hence. Waiting for the US to realize necessary and inevitable progress is a mug’s game.

I confess that I’m very Euro/America-centric in my socio-political doom-tracking. I really ought to give fair due to Indian ethno-nationalism, Russian counter-intelligence, African famine, Arab revolutions and South American neo-fascism. Sorry, I’m Canadian. After worrying about the US and the UK, there are barely any hours left in a day. Read more »