by Peter Wells

Saving endangered languages is an activity the virtue of which seems to be beyond question among Western liberals. Endangered languages, as conventionally identified, are usually spoken by poor and vulnerable people in remote areas of developing countries, so our sympathies are engaged. The least we could do, it seems, to alleviate their misery and show solidarity with them, would be to preserve their language.

At the same time, it is also urged that the endangered languages are valuable in themselves. Followers of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (Linguistic Relativity) assert that each individual language can express concepts which no other language can express. Therefore, they insist that it is important not only to record these languages before they die, but also to keep the language communities alive so that they continue to use them.

I wish to suggest that this project, while well-meaning, is ill-conceived. It seems to employ an unscientific definition of the term ‘language’, and to rely upon a disputed theory about the nature of language. It is unrealistic in terms of what carrying it out would involve, and finally, and most importantly from the point of view of liberalism, it would tend to reduce, rather than increase, freedom. Read more »

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

Some people claim that the prominent display of statues to controversial events or people, such as confederate generals in the southern United States, merely memorialises historical facts that unfortunately make some people uncomfortable. This is false. Firstly, such statues have nothing to do with history or facts and everything to do with projecting an illiberal political domination into the future. Secondly, upsetting a certain group of people is not an accident but exactly what they are supposed to do.

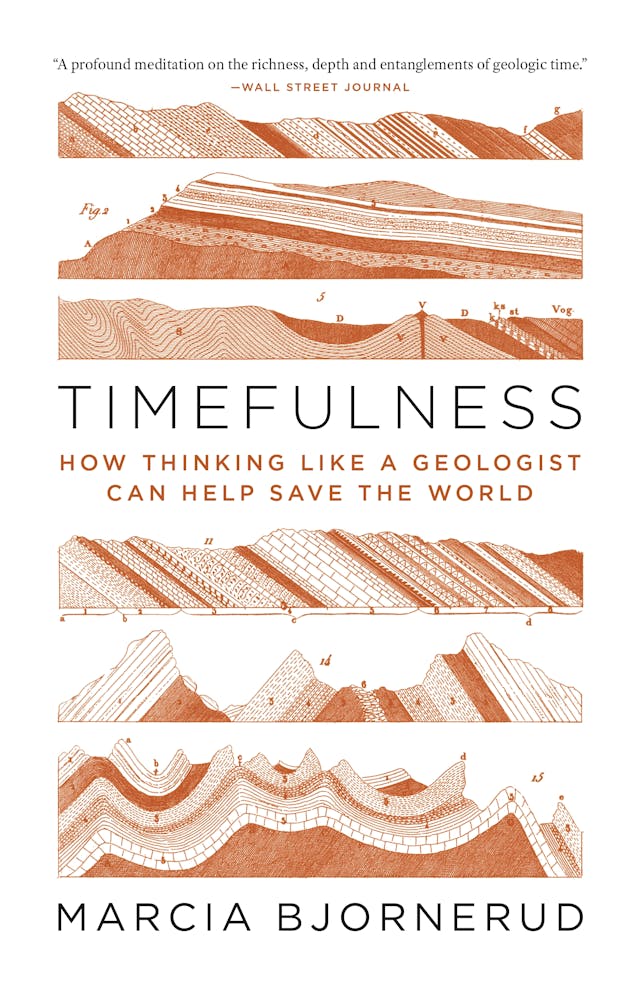

by Paul Braterman

by Paul Braterman

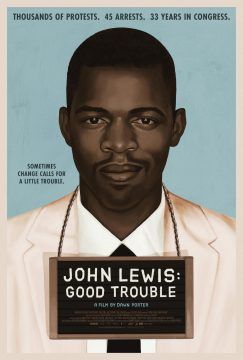

John Lewis: Good Trouble

John Lewis: Good Trouble

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time.

The coronavirus pandemic has massively disrupted the working lives of millions of people. For those who have lost their jobs, income, or work-related benefits, this can mean serious hardship and anxiety. For others, it has meant getting used to new routines and methods of working. For all of us, though, it should prompt reflection on how we think about work in general–both as a curse and as a blessing. Here, I want to focus on how work relates to time. Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up.

Beauty has long been associated with moments in life that cannot easily be spoken of—what is often called “the ineffable”. When astonished or transfixed by nature, a work or art, or a bottle of wine, words even when finely voiced seem inadequate. Are words destined to fail? Can we not share anything of the experience of beauty? On the one hand, the experience of beauty is private; it is after all my experience not someone else’s. But, on the other hand, we seem to have a great need to share our experiences. Words fail but that doesn’t get us to shut up. In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.

In a survey released at the end of May by the AP and the NORC Center for public affairs research, 49% of Americans said they intended to be vaccinated against the new coronavirus, 31% said they were unsure, and 20% said they would not get the vaccine.

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long