by Sarah Firisen

“I’m bored!”. How often I would whine that as a kid. How often my kids would whine that to me. “Go out and play” my mother would reply. I probably said some version of the same thing to my kids. And I usually would go out and play. I’d go to the park and wander in the wooded area making up stories and collecting flowers that I’d later dry between the pages of books. Or I’d go and knock on a neighbor’s door to see if a friend could come out and play. Then we’d ride our bikes, or practice doing handstands against someone’s house. Sometimes we had water fights or snowball fights in winter. I suspect that kids today spend less time rectifying boredom in these kinds of ways, as indeed do most adults. After all, between streaming media and mobile devices, who really needs to be bored anymore. A game of Words with Friends or Candy Crush, or a new show on Netflix is never more than a tap away.

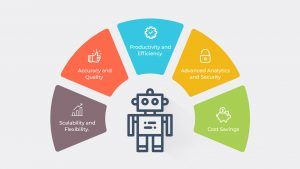

And now, with automation in the workplace easier and more affordable than ever, the prospect of work without boredom is increasingly before us. We all have those tasks that we hate, normally the boring repetitive ones that just have to get done. It’s the rare job that doesn’t have some degree of mundane administrative activities attached to it. But thanks to AI and particularly Robotic Process Automation (RPA), companies, and increasingly individual employees, are able to automate many of these tasks. Anything that is a rules based activity that can be done at a keyboard is a likely candidate for RPA bots. These bots can be run server-side for enterprise-wide processes or from your computer, mimicking whatever security access your company account has to systems on your computer and throughout the network, including accessing web pages and scraping information. Many hours can be taken out of a worker’s days, with tasks performed more quickly and more accurately by these bots, and with the added advantage of being able to run anytime of the day and night 24/7. Leaving many white collar workers with the not so distant prospect of never having to do those kinds of tasks again. And while it is very possible, and even likely, that many if not most companies see at least some of return on investment from this technology as a reduction in their workforce, at least the stated goal of many companies is to free their workers up to perform higher value work.

In his book Drive, Daniel Pink argues that, once you’ve passed the threshold of being paid an adequate amount for everyday living, motivation at works becomes far more about autonomy, mastery, and purpose than about money. And when we reflect on the parts of our jobs, of our lives, that are rewarding, that makes sense. No one has ever said that the best part of their day is filling in timesheets, or creating invoices, or any of those repetitive, mundane tasks that most jobs have as some component. So what would a work day look like that was only filled with the activities that play to our strengths and our passions? We’re on the cusp of a work revolution where most if not all of those boring, repetitive, but necessary jobs can be automated. We’re on the cusp of a future without boredom where worker’s days can be freed up to to focus on more interesting and creative work? The kind of work that motivates people and can be a differentiator in their careers.

On the face of it, this sounds wonderful. Most of us spend most of our waking hours at our jobs. If more of that time were interesting, creative, meaningful work, how could that be anything other than a plus? Well there are a few obvious points to raise: there are many people who are employed precisely to do these “boring”, repetitive tasks. If those tasks are automated, it doesn’t necessarily follow that all these people can now be relocated more interesting and creative work. And of course, while many people would love to be more creatively and intellectually challenged, not everyone wants to be or feels up for such tasks. What is boring to me me, isn’t necessarily boring to someone else, but it may still be a task ripe for automation.

Computer programs were originally written for the most part by computer science-trained experts, writing in machine code that had to be constructed to do everything including hardware memory management. These languages have given way to higher-level languages that are easier to write in while being far more powerful. The “automation” (so to speak) of the more basic and often boring aspects of computer programming has certainly not shrunk the demand for software developers, far from it. And you can go through innovation after innovation and say the same thing; the creation of the modern spreadsheet application and it’s replacement of many of the tasks involved in doing such work manually on a piece of paper can only be seen as a good thing. There aren’t less financial analysts or accountants, they’re just able to focus on more value-added activities rather than double and triple checking their math as they try to add rows and columns.

Of course, there are people who will say that software developers today, mostly don’t have the same understanding of how to control computer memory management as their predecessors and have lost a valuable skill. Again, hasn’t this always been the way? You can look at the entire spectrum of human activity and see that with innovation and technological progress there has always been the loss of more mundane skills. For the most part, we shrug our shoulders and move on. Humans are very adaptable, if we ever had to use those skills again, couldn’t we just learn them? There’s no doubt that my children are not as good at spelling as I had to be in school, they type everything these days and use spell check. Is this really so terrible? They can focus on what they’re trying to write rather than worrying about the technical details. They can focus on being more creative, more insightful, more interesting.

One aspect of the automation revolution that worries me, and that I’ve written about before, is that I think that, because the rate of automation is exponentially so much faster than in the past, we do run the risk that the apprenticeship model, that is common in most industries to one degree or another, will be severely disrupted; it’s by doing the lower level, more mundane work that a young accountant learns the business. It’s hard to imagine a world where a 22-year old walks out of college and is immediately ready for the C-Suite. But if all the lower-level work is automated, how are they to learn and work their way up? Again, you could look at the software development model and say, how is it different? But I think that this is a different paradigm and there will need to be a real shift in how companies think about training younger staff to be able to tackle the more strategic, creative work.

So a future without boredom may really be before many of us, at least those of us in white collar professions. But doesn’t boredom have some benefits? Is it the case that doing nothing, or at the very least, doing something “boring”, repetitive, mundane might actually have some cognitive benefits? If nothing else, as this Psychology Today article points out “boredom can also be your way of telling yourself that you’re not spending your time as well as you could, that you should rather be doing something else, something more enjoyable or more useful, or more important and fulfilling.

And so boredom can be a stimulus for change, leading you to better ideas, higher ambitions, and greater opportunities. Most of our achievements, of man’s achievements, are born out of the dread of boredom.”

Isn’t the idea that we can spend all of our waking time being “on”, being creative and strategic actually a fundamental misunderstanding of the way that human creativity actually works?, “boredom isn’t all bad. By encouraging contemplation and daydreaming, it can spur creativity.“

A fascinating New Yorker article a decade ago talked about the eureka experience; suddenly having an insight, an answer to a problem, that is both an instantaneous illumination and is accompanied by a certainty of its accuracy. I won’t try to replicate the explanation of the science involved (the article is worth reading), except to quote this “At first, the brain lavishes the scarce resource of attention on a single problem. But, once the brain is sufficiently focussed, the cortex needs to relax in order to seek out the more remote association in the right hemisphere, which will provide the insight. “The relaxation phase is crucial,””. The thinking is that this is why we often have our aha moments when we’re in the shower, or when we first wake up in the morning. In my days as a software developer, I would often have the experience where I would spend a whole day worrying away at a particular coding puzzle only to solve it in the 5 minute walk from the office to my car. This is one of the reasons that companies like Google are smart to have foosball tables and the like in their offices, people need down time in order to being creative and solve problems.

This isn’t to say that without more mundane tasks in their daily work people can’t be creative problem solvers. But it is to say that, if nothing else,we need to make sure that as we take boredom out of life and the workplace, we don’t replace it with an expectations of constant creative uptime. As tempting as it may be for companies to try to swap out 8 hours a day of mundane, repetitive tasks for 8 hours of constant creativity, they’re going to have to think more creatively themselves about what really are the most productive ways for their employees to to manage a future without boredom.