The Eisack river is like this in Franzensfeste today. It is roaring down with a stupendous amount of water at incredible speed and with a kind of violent force which is frightening to behold. And to top it off, it is rolling large stones along which crash into each other under water and sound like thunder (at least that is what I am told those deep booms come from). It is an awesome sight and sound. This massive flow of water is headed toward Brixen as it cannot be held by the dam in Franzensfeste (the dam reservoir is already almost overflowing) and it may break over its banks in Brixen and further downriver in Klausen (where people in low-lying areas are already being told to move to higher ground, sandbags are being placed, etc.). If one were to fall into the river anywhere today, one would not survive more than a few seconds and would be smashed against the rocks on the riverbed with bone-breaking force almost instantly. I can hear it loudly even as I sit across the street at my desk.

Here is a video I made of the Eisack by the time it is in Brixen. Watch full screen and with sound on. You will see just how wild the river is by the end and how it is flowing very hard and fast and muddy and sometimes spontaneously bursts skyward in plumes as it goes forth frothing and foaming through Brixen. Keep in mind, the video has been slowed down by a factor of 10 (shot at 250 frames/sec) so it is a bit hard to tell just how fast the water is moving.

It is commonplace to observe just how marvelous books are. Some person, perhaps from long ago, makes inky marks onto processed pulp from old trees. The ensuing artifact is tossed from hand to hand, carrying its cargo of characters, plots, ideas, and poems across the rough seas of time, until it comes to you. And now you have the chance to share in a tradition of readers stretching back to the author, a transtemporal book club who communicate with one another only by terse comments scratched into the margins of this leather-bound vessel.

It is commonplace to observe just how marvelous books are. Some person, perhaps from long ago, makes inky marks onto processed pulp from old trees. The ensuing artifact is tossed from hand to hand, carrying its cargo of characters, plots, ideas, and poems across the rough seas of time, until it comes to you. And now you have the chance to share in a tradition of readers stretching back to the author, a transtemporal book club who communicate with one another only by terse comments scratched into the margins of this leather-bound vessel. My mother believed that games were good for you. Her faith was unshaken by the occasions when my brothers and I returned from our outdoor games with a grievance between us, or by the times the Monopoly board was overturned in anger during the winter months. She considered that games were a preparation for life. I think she underestimated them.

My mother believed that games were good for you. Her faith was unshaken by the occasions when my brothers and I returned from our outdoor games with a grievance between us, or by the times the Monopoly board was overturned in anger during the winter months. She considered that games were a preparation for life. I think she underestimated them.

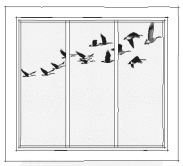

first their concerted honks—

first their concerted honks—

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a great of suffering and has disrupted millions of lives. Few people welcome this kind of disruption; but as many have already observed, it can be the occasion for reflection, particularly on aspects of our lives that are called into question, appear in a new light, or that we were taking for granted but whose absence now makes us realize were very precious. For many people, work, which is so central to their lives, is one of the things that has been especially disrupted. The pandemic has affected how they do their job, how they experience it, or whether they even still have a job at all. For those who are working from home rather than commuting to a workplace shared with co-workers, the new situation is likely to bring a new awareness of the relation between work and time. So let us reflect on this.

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality.

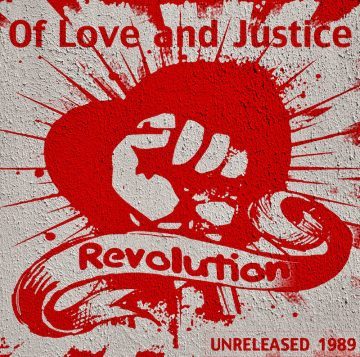

I often hear it said that, despite all the stories about family and cultural traditions, winemaking ideologies, and paeans to terroir, what matters is what’s in the glass. If a wine has flavor it’s good. Nothing else matters. And, of course, the whole idea of wine scores reflects the idea that there is single scale of deliciousness that defines wine quality. Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.

Finally, outrage. Intense, violent, peaceful, burning, painful, heart-wrenching, passionate, empowering, joyful, loving outrage. Finally. We have, for decades, lived with the violence of erasure, silencing, the carceral state, economic pain, hunger, poverty, marginalization, humiliation, colonization, juridical racism, and sexual objectification. Our outrage is collective, multi-ethnic, cross-gendered and includes people from across the economic spectrum. One match does not start a firestorm unless what it touches is primed to burn. But unlike other moments of outrage that have briefly erupted over the years in the face of death and injustice, there seems to be something different this time; our outrage burns with a kind of love not seen or felt since Selma and Stonewall. Every scream against white supremacy, each interlocked arm that refuses to yield, every step we take along roads paved in blood and sweat, each drop of milk poured over eyes burning from pepper spray, every fist raised in solidarity, each time we are afraid but keep fighting is a sign that radical love has returned with a vengeance.