by Timothy Don

In my capacity as art editor at Lapham’s Quarterly, I’ve spent the last six weeks researching images for our upcoming issue on TRADE. It was not a thematic that excited me when I started, I have to admit—I’m a curator and a writer, not a businessman or an economist, dammit! But after looking at more than 10,000 paintings, sculptures, and photographs that limn the human urge to exchange goods, a faint thrill and a growing sense of despair have both begun to take root.I’ve peered into the faces of Ferdinand Bol’s Syndics of the Wine Traders Guild of Amsterdam from 1660, looking for signs of avarice, prudence, and rectitude.

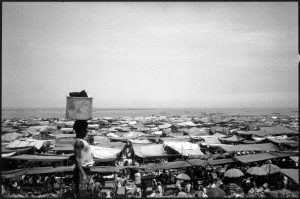

I’ve turned in my hands a 3rd century terracotta figurine of a camel carrying transport amphora (a secular, material expression of the nativity scene I just disassembled with my daughter). I’ve flipped through Alex Majoli’s 1999 series of photographs of the Roque Santeiro in Angola, the largest open-air market in Africa. According to Alex, the Roque attracts roughly one million people per day, and its vendors sell anything and everything: food, weapons, drugs, even people. It hosts church services and marriages. It shelters war cripples, homeless refugees, police, prostitutes, and the insane. Babies are born and the dead are interred within and beneath its stalls. At this “market of the damned,” Hieronymus Bosch’s 15th century visions of hell have been fully realized by the predations of 20th century capitalism.

A line and a theme have emerged through the iconography I’ve been following: to trade is human. We buy and we sell; we exchange, barter, haggle, negotiate, promise, vouchsafe, con, steal, acquire, and unload. It’s what we do; it’s what we’ve always done. The allure of trade lies not so much in the goods amassed as in the frisson of exchange: the contact with another human being that occurs in the act of trade. The slipping-ness from one to another. The handshake, the greased palm, the unctuous smile. The flow, the liquidity. The intimate bond that is established between two people when they make a deal. To trade is human. It’s dirty and oily and sexy.

And yet, underneath trade, there is something else going on. Something very faint, something very fragile, something that only adds to the excitement and the value of the goods on the table, is put at risk each time a trade is made. This something is trust.

One can insure and indemnify, initial the pre-nup and sign on the dotted line, hedge one’s bets and engage in arbitrage. But one can always get screwed, because ultimately, in every act of trade, the thing being exchanged is trust. And there is no way to make sure that the person you’re doing business with is trustworthy until after the fact, until you have risked trusting her. To trade is human. But the daemonic force, the divine spark that drives and enlightens trade, is trust. No trust? No deal. No trust? No love. No trust? No trade.

Of the many horrors and obscenitites that 2018 has served up over the last twelve months, one of the most pernicious has been the series of betrayals and the accompanying erosion of trust among nations, partners, parties, allies, genders, and individuals. It’s easy to lay the blame for this at the feet of our Bully-in-Chief, a maniac masquerading as a businessman who has reduced all relationships to a game of Texas Hold ’Em in which he has the Big Stack and refuses to play by the rules, or by any sense of logic whatsoever. But every age, as Danielle Allen once told me, gets the President it deserves. Ours is the age of a mistrust so deep that it verges on paranoia and turns all trade—economic or emotional—into rank exploitation. 2018’s lesson: Trust no one. Not your president nor your party. Neither your neighbor nor your newsfeed, your sibling nor your spouse nor your friend. Do not trust men or judges or the court. If one must trust—and one must—then trust your foe. You can rely on your foe. Surely it is not inconsequential or pure coincidence that at the close of the year our markets and our economies are floundering. Without trust there is no trade.

This phenomenon, this hellscape of mistrust through which we are obliged to move like zombies on steroids, was brought home to me on a person-to-person level quite recently. It had been a weekend over the course of which I had hosted a sleepover, done the laundry, cooked the breakfasts, lunches, and dinners, folded the laundry, flossed the teeth, and coached both my children’s soccer teams. I had even gotten them up and fed and washed, awake for and attentive to church on Sunday morning. It had been a good weekend, at the end of which we decided to take a break, head to the hills, and have a picnic. San Pelligrinos for them, cold beer for me, a roast chicken to share. We jumped into the car and headed out to the Safeway to get the chicken. “Do you want to come in with me?” I asked them, “or do you prefer to stay in the car with the doors locked, the windows cracked, and The Chronicles of Narnia to read to each other? I’ll be gone for ninety seconds.”

“Let us stay here, Papa, we’ll be fine.” And I knew they would. They’re smart and they’re careful and they’re kind (I trust them), so I parked the car in the sun on a corner next to a lovely café with lots of petits bourgeois enjoying their lattes and dashed in to get the chicken. I was back at the car eighty-three seconds later and there was a young woman standing nearby. “Are these your children?” she asked as I opened the hatch and put in the chicken. “Is this your car?”

I took a deep breath. “Yes indeed they are and yes it is.”

“Do you know you left them alone in the car.” It was not a question but I answered it anyway.

“Yes, I do know that, and yes I did.”

“You shouldn’t do that, you know.”

“Ok,” I said, “Well…thanks very much! We’re off to have a picnic now. Have a nice day!”

She took a step towards me. “There are predators in this neighborhood, you know.” I looked at her at that point, looked at her boyfriend, who glanced at me and dropped his head with an almost audible sigh into the palm of his hand; I looked at the café and the street corner and the trees and all the people. It was a beautiful day, warm in the sun and cool in the shade. Everyone was carrying grocery bags overflowing with food and flowers. Someone walked past with the most gorgeous dog I have ever seen on a leash. Its fur was glossy, black, and luminous.

I closed the hatch of the car and took another breath. “Ummm…Do you think you might be able to save some other corner of the universe right now? We’re doing just fine here, as far as I can tell.”

“There are predators in this neighborhood. And you’re a terrible father,” she said to me.

I got into the vehicle and gripped the steering wheel until my knuckles went white and then turned to my children. “Are you guys ok?”

“Yes, Papa, we’re fine,” my son said. “What did that woman want?”

“I’m not exactly sure,” I said to him. “She had a very busy body. What did she say to you?”

“Well she came to the window,” my daughter piped in, “and asked where our papa was.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And then she asked if we were OK.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And then she told us not to talk to strangers.”

“Huh,” I said. “What did you say to that?”

My daughter looked me direct in the eyes and smiled wickedly. “I said to her, ‘You mean…like you?’”

All three of us laughed, hard, at that point. But as I drove up into the hills to enjoy our picnic, I realized that I had just met a person who trusts no one, the embodiment of everything we have gone through this year. 2018’s Person of the Year.

It is not possible to be in the world without trust, and yet we live in a world that seems hellbent on betraying our trust in it and in its people. I had betrayed that woman’s trust in Father; she betrayed mine in Neighbor. The result was a mutual impoverishment. Mistrust impoverishes trade, whether you’re trading a smile or a kind word or an idea or a recommendation or a commodity. 2018: the year of mistrust.

Let’s make 2019 different. May it be profitable. May it be full of trade. May it be overflowing with trust. Happy new year!