by Robert Fay

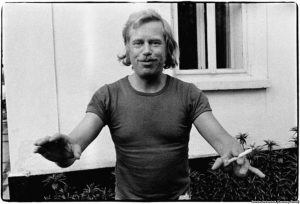

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend Jan Tříska, who would emigrate to the U.S. in 1977 and eventually appear in The Karate Kid III (I’m not making this up), while Havel went on in 1989 to became president of a free Czechoslovakia (equally astonishing). But on that summer morning, these two men were still just creatures of the Prague theatre world. They caroused at night with their artist and intellectual companions, slept-in late and then worked diligently on their respective crafts in the afternoons, much as their colleagues in London or Paris did.

On the morning of August 20, 1968, the Czech playwright Vaclav Havel had a serious hangover. He was at his country home in Liberec after a night of boozing it up with his actor friend Jan Tříska, who would emigrate to the U.S. in 1977 and eventually appear in The Karate Kid III (I’m not making this up), while Havel went on in 1989 to became president of a free Czechoslovakia (equally astonishing). But on that summer morning, these two men were still just creatures of the Prague theatre world. They caroused at night with their artist and intellectual companions, slept-in late and then worked diligently on their respective crafts in the afternoons, much as their colleagues in London or Paris did.

But these familiar routines came to a halt promptly on August 20 when the Warsaw Pact nations, led by the Soviet Union, invaded Czechoslovakia, ending eight months of political reform and expanded social and civic freedoms that has become known as “The Prague Spring.”

In the popular western imagination, the Prague Spring has been both sacralized and completely mischaracterized. It’s been crudely lumped in with the 1960s political unrest in the West, something like: “The Summer of Love—Slavic Style.” But the anti-establishment, countercultural youth rebellions (sexual freedom, drug use, feminism, gay rights, etc.) that were visible in cities like Paris, London and San Francisco had little in common with the Prague Spring.

In the U.S., the protests centered on critiques of American military involvement in Vietnam and on social injustices committed against African Americans, while in France, the social unrest was an explicit attack on capitalism by students, workers and members of the French communist and socialist parties, who were united against President Charles de Gaulle, and the conservative forces he represented.

Reform Movement, Not Revolution

In contrast, the Prague Spring was primarily a reform movement within the KSR (The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia). It was an attempt by KSR members to change the party…a little. Maybe experiment with new ways of managing the economy, as well as loosening censorship laws. The Prague Spring was not (primarily) idealistic 20-year-olds in the streets, but “old men,” communist old men in power, who were looking to reform one-party rule in Czechoslovakia, not overturn it.

Now there is no doubt the changes and the appointment of reform-minded Alexander Dubček in January 1968 as First Secretary of the KSR, inspired artists and intellectuals (and the population at large) to start dreaming, talking, criticizing and imagining a country free of foreign intervention and the rule of one party. But the Czechs weren’t trying to imitate George Washington or Che Guevara. This was an attempt at achieving “socialism with a human face.”

Russian Historian Vladislav Zubok in The Prague Spring and the Warsaw Pact Invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 (2010) writes of how Soviet dissidents viewed the external political events of 1968:

“The Prague Spring was closer to the hearts and minds of the Moscow-based intellectuals and artists than the Western New Left radicalism that erupted at the same time. The anti-Vietnam protests among radical youth in the West did not find the slightest response in the quarters of the dissident movement. Moscow intellectuals also refused to share the Western radical infatuation with Maoist Cultural revolution in China. In the opinion of one Moscow witness of the May events in Paris, French neo-Marxist intellectuals and students were ‘possessed by Satanic powers.’ They worshiped revolutionary violence, while Soviet liberals and reform Communists abhorred it.”

Havel also disapproved, in his own way, of the “neo-Marxist’ crowd in the West. In the spring of 1968 he traveled to New York City to see a production of one of his plays and also made time to visit England.

During the trip, he saw firsthand the youth protests. Havel’s biographer Michael Zantovksy writes in Havel: A Life (2014) that Havel was sympathetic to the “release of youthful energy” in 1968, but he was not supportive of “attaining freedom through violence, hallucinatory visions or free sex,” and was certainly “astonished that people could dream of introducing voluntarily the same kind of doctrinaire, tyrannical system he and his countrymen were busy trying to dismantle at that very moment.”

Calling All Writers

When Havel learned the news that the Soviets had invaded, his first instinct wasn’t to grab a rifle or to draft an essay, but to volunteer for resistance service with Czechoslovakia Radio. And so, in the first few hours of the day, as Soviet tanks and airborne divisions swarmed over the country, Havel prudently decided to use the airwaves to call for help. But instead of requesting NATO infantry divisions, he called upon more subtle forces of opposition, his writer colleagues abroad, men like Gunter Grass, Kingsley Amis, Max Frisch, Jean-Paul Sartre, Arthur Miller and Samuel Beckett, to name a few. And though these writers did not fire a single rifle round at Soviet troops, they began to write and speak about the invasion, drawing the West’s attention to the Soviet’s violation of Czechoslovakia.

A few days later, the Communist Party in North Bohemia published a manual in Liberec titled To All Citizens. It was a how-to-manual for dealing with the invading soldiers. Havel was most certainly one of its principal authors. “Approach the presence of foreign troops as you would approach, for example, a natural disaster,” Havel wrote. “Do not negotiate with them—just as you would not negotiate with torrential rain—but deal with them and escape them just as you would escape rain: use your wits, intelligence and your fantasy.”

The image of a rainstorm with its inherent irrationality is the perfect metaphor to guide people through an irrational nightmare: suddenly, with no warning, a Russian solider with an AK-47 has appeared in your backyard. He doesn’t speak Czech. He has tremendous power over you and your family and he likely has no understanding of why he has been ordered to tromp around Bohemia.

The Good Soldier Švejk

The pamphlet continues—in a truly Havalian touch—to evoke two Czech models of behavior for interacting with these dangerous foreigners. The models are drawn from both literature and history: “If at certain moments you decide that it is more appropriate to behave like (Jan) Hus, behave like Hus. If you, on the other hand, you decide it is more effective to behave like Švejk, behave like Švejk.”

In our current world, it’s an imaginable bit of political prose. You have the future president of Czechoslovakia, and at the time, the de-facto spokesman for the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, advising citizens to navigate a dangerous and complex situation by acting like a medieval clergyman or a character from a Czech novel. Jan Hus was a Czech Catholic priest and reformer in the late 14th and early 15th century who attacked Church corruption. He was accused of being a heretic, excommunicated and burned at the stake after refusing to recant.

Švejk is the protagonist from the novel The Good Soldier Švejk (1921-23) by Jaroslav Hašek. The book is a Czech classic, beloved and revered in the way The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is in the U.S. Švejk is a Czech simpleton who serves in the Austrio-Hungarian empire during the First World War, and his behavior is so simple and pure that people cannot decided if he is undermining the army or is just an imbecile. The American equivalent (though not an exact one) would be the bumbling Marine Gomer Pyle in the popular 1960s television show Gomer Pyle U.S.M.C.

It is unimaginable that an American leader would advise Americans to deal with invading Chinese troops, for example, by acting like the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz or the character Bartleby from Herman Melville’s short story, “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street.” But the Czechs, being a small nation crammed into central Europe, have had to digest far different lessons than the peoples of larger countries.

It was understandable that Havel evoked Švejk because the Czechs have learned to admire characteristics contrary to those associated with patrician, martial leaders such as Charles de Gaulle, Winston Churchill and Teddy Roosevelt. Not being able to resort to brute force, the Czechs have learned to appreciate the more subtle man, the reflective man, even the weak man. Czech novelist Pavel Kohout was active during the Prague Spring and wrote in his memoir From the Diary of a Counter Revolutionary (1969) of how this Czech affinity flowered during the brief leadership of Dubček in 1968:

“(Dubček’s) real magic, with which he enchanted old ladies in retirement as much as university professors, lay in his weakness. After the divine leaders of the Stalin era, who had insisted that the photographers retouch every pimple and radio technicians remove all sibilants from their broadcasts, it was pure joy to watch a man who seemed to be dying of stage fright.”

Havel for Today’s World

The vulnerable, authentic leader with stage fright is nowhere to be seen today. In fact, the current list of political leaders with nationalist, strong-man tendencies, who toy with authoritarian impulses, continues to grow by the day. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro has recently joined a list that includes Donald Trump, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Italy’s Interior Minister Matteo Salvini.

There is a lot of consternation in the West about this turn to the right. There are fears that the age of liberal democracies is in eclipse. In the U.S., opposition to Donald Trump’s nationalist regime takes the form of a partisan fight, with predictable legislative gridlock and a conviction among citizens that all politicians, left and right, are motivated by self-interest alone.

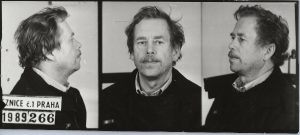

Havel remained deeply skeptical about the value of political parties. He was never a member of the KSR and during the bad years of the 1970s when he was hounded, harassed and spied on by the StB, the secret police, he didn’t like to think of himself as a political activist or dissident, preferring the term “public intellectual” instead.

Havel believed that what existed in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s—he described it a post-totalitarian society—wasn’t “the manifestation of a political line followed by a political government”—but simply a fundamental assault on humanity and truth itself, and “humans stand against it alone, abandoned and isolated.”

In his famed 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless,” he notes how dissident political groups and parties in Poland and Czechoslovakia had become naturally defensive in their outlook. But Havel believed this was a fundamental flaw, because politics should be about proposing positive solutions. “Politics always assumes a positive program and can scarcely limit itself to defending someone from something,” he wrote.

There is an important lesson here. Citizens and political leaders opposed to Donald Trump, for example, can’t win by articulating the most artful and sweeping condemnation of Trumpism. He is not an ideology or a political platform, but the expression of a system that seeks to degrade human beings, first by desecrating the truth, and then by degrading life itself. The opponents of Trump must “live within the truth,” and offer citizens a positive program that affirms the aims of life, which are hope, love, family, adventure, art, work, religion and everything else that is inexplicable and wondrous in the human experience.

The American people, for one, need the following advice on how to deal with the life-denying nationalists and racists in their country: “If at certain moments you decide that it is more appropriate to behave like Abe Lincoln, behave like Abe Lincoln. If you, on the other hand, decide it is more effective to behave like Robin Williams, behave like Robin Williams.”

Robert Fay’s essays, reviews and stories have appeared in The Atlantic, The Millions, The Los Angeles Review of Books and The Chicago Quarterly Review, among others. He is co-creator of the Feeling Bookish Podcast. Follow him on Twitter @RobertFay1.