by Philip Graham

Although my love of music goes back to the glory days of the long-playing vinyl album, I’ve embraced all the succeeding platform incarnations, from tapes to CDs to downloading to streaming (well, not so much streaming—shame on you, Spotify, for disappearing musicians’ royalties down to the teeniest fraction of a penny). But I hate to confess that while I can recognize a modulation, I’d be hard pressed to tell you from what key to the other. My knowledge of musical notation remains shaky, and sometimes I can’t distinguish between an alto and a tenor saxophone on a recording. I never learned to play an instrument. When clapping along at a singer’s request (remember those ancient concert rituals?), I begin cautiously, afraid to undermine the rhythm of my neighbors. I can’t even snap my fingers. So why imagine I can write about music?

I don’t know what exact percentages of nitrogen, oxygen, argon, carbon dioxide and water vapor make up the air, but still I breathe. And I will inhale any genre of music with delight. In a movie theater I sometimes wait to the end of the interminable final credits so I can locate the name of a song whose snippet in a minor scene erased for me the rest of the film. All my books have been written with music offering a friendly counterpoint—each page holds the echo of a secret playlist.

I almost never hesitate to track down an intriguing, unfamiliar song. It’s impossible to predict when such a moment will arrive. Certainly there was no warning that night near the end of my last semester at college. The threat of graduation had reared up too quickly, and with a sense of doom I parked myself at a free table in the school’s library—always a cozy place to study, tucked as it was (some might say crammed) into the first floor of one of the oldest buildings on campus, its presence nearly lost beneath the two upper floors reserved for dorm rooms. Read more »

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms.

In the Age of Trump, the banality of evil can perhaps best be defined as unfettered self-interest. Banal because everyone has self-interest, and because American culture expects and even celebrates its most gratuitous pursuits and expressions. Evil because, when unchecked, self-interest leads not only to intolerable disparities in wealth and power, but eventually the erosion of democratic norms. I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil.

I may rise in the morning and notice that a long overdue spring rainfall has revived the flagging vegetation in my kitchen garden. I may give thanks to an unseen, benevolent power for this respite from a protracted and wasting drought. And I may record in my journal: “The heavens cannot horde the juice eternal / The sun draws from the thirsty acres vernal.” In such exercises, I will not have practised rigorous inquiry into the causes of things; I will not have subscribed to any particular view of the metaphysical; and I will certainly not have produced literature. But I will have replicated the conditions for the birth of science, as sketched by Geoffrey Lloyd in his account of the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first thinkers (at least in the Western world) to consider natural phenomena as distinct from the supernatural, however devoutly they may have believed in the latter; and who frequently set down their observations, theories and conclusions in formal language. For my observation of a natural phenomenon (rain and its effect on plant life), while not methodical, would bespeak a willingness to collect and consider empirical data unconstrained by superstitious tradition, and would not necessarily be contradicted by my ensuing prayer of gratitude to a supernatural force; and the verse elaboration of my findings into a speculative theory would not consign them to the realm of poetry (or even doggerel), but would merely represent a formal convention, whose forebears include Hesiod, Xenophanes, Lucretius and Vergil. Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

Rutger Bregman’s Humankind: A Hopeful History is a clearly written argument if ever there was one. Bregman believes humans are a kind species and that we should arrange society accordingly. The reason why this thesis needs intellectual support at all is not that it is particularly profound or complicated, but that there are so many misunderstandings to be cleared away, so many apparent objections that need to be overcome.

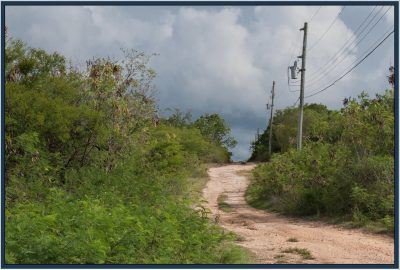

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Anguilla is a sandbar ten miles long. It’s three miles wide if you’re being generous, but generous isn’t a word that pairs well with the endowments of a small, arid skerry of sand pocked with salt ponds.

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

Physics writing, let’s face it, is usually pretty boring. In a recent

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

I have a friend who is a self-described “cop magnet.” He’s been arrested six or seven times, just standing there.

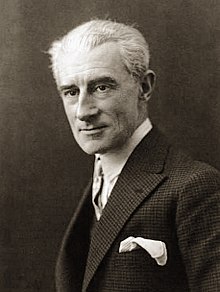

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to

Lately I’ve been craving the music of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). As reality continues to be fraught, in the midst of a pandemic, social unrest, culture wars, and on and on, Ravel’s music offers an enticing escape. Described by his close friend, concert pianist Ricardo Viñes, as “inclined by temperament toward the poetic and fanciful,” Ravel created music that continues to captivate with its otherworldly beauty. Another reason for his appeal now, when the public health crisis has disrupted all of our quotidian rhythms, is that rhythm is the sine qua non of Ravel’s art. All you have to do is listen to