by Michael Liss

What is it about immigration that causes us to lose our minds?

I’m not even referring to the absurd spectacle of toilets overflowing at national monuments and hundreds of thousands of federal workers going without pay. In theory, at least, there’s a reason for that: The President promised his supporters a magnificent structure across the Southern Border, and the Democrats don’t want to advance Mexico the money to pay for it.

I’m talking about the insanity of not addressing the root issue—actual immigration policy. Let’s be honest with ourselves, a few billion dollars for something that seems to be morphing in composition and cost every day doesn’t solve our immigration woes. It doesn’t build a Wall, either. We would be taking on the largest infrastructure project since the build-out of the national highway system, lasting many years and including enough eminent domain (because a considerable amount of border land in Texas is in private hands) to cause conservative heads to explode. A few billion is barely seed money for the lobbyists.

So, let’s talk about what we should be talking about: Immigration policy. And let’s start with a hypothetical: The nation has decided to make you Immigration Czar. You have the absolute power to determine policy for the next two years. What do you want to do with it?

Before you begin this glorious-but-thankless quest, I have to include two pre-conditions.

First, you start with the country we have now. You can be as generous, or ruthless and arbitrary as you would like, but the law matters. You cannot assume authority greater than already exists: No giving of universal citizenship, or retroactive revocation of citizenship or permanent residencies previously granted. No magic wand that returns you to the demographics of 1950. No fanciful interpretations of the Constitution or Supreme Court decisions. Be bold if you like, but observe the guardrails.

Second, you understand that we live in a republic, and while we’ve given you this power now, you are an American-Style Czar, but not an Emperor, and anything you do automatically sunsets in two years and defaults back into the current mess unless reauthorized by Congress and signed by the then President. So, make it good, or expect it to blow up.

Adherence to law and attempting to make something balanced enough so that people would keep it? Takes all the fun out of it. If it’s going to be this unrewarding, you might reasonably ask, why would we need a Czar at all? After all, we collectively have always had the power to set limits, to enshrine our preferences and our prejudices into law, to build walls, to intern, imprison and deport, to reject even those with a legitimate fear of persecution and death. And we have acted on those powers, more than 40 times by the venerable and quaint “how a bill becomes a law” technique, and many more through enforcement tweaks (and yanks) by the Executive Branch.

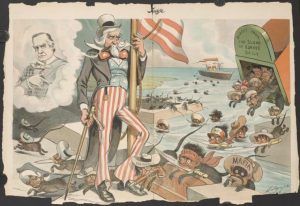

Not all of those choices show us in the best possible light. After we argued for many decades and then fought a Civil War over the status of those of African descent, we turned our animus towards the Chinese. We legislated against them, several times, including the evocatively-named Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. But that didn’t settle our fears. Immigration absorbed us so much we went back to the well seven more times between 1882 and 1907, before deciding in 1918 that it wasn’t just the Chinese who should be verboten, but, to feel culturally safe, we also needed an entire “Asiatic Barred Zone.” In 1921, we were so overwhelmed by non-barred people that we instituted actual quotas: In any calendar year, the maximum any country could send us was 3% of the total number of people from that country who were already in the US, as of the 1910 Census. Eventually, we turned our eyes to a more dangerous type: Communists. And then, the perennially terrifying Mexicans, culminating in 1954’s “Operation Wetback,” from which it is estimated that 1.3 million Mexicans were either deported or left. More recently, we’ve waxed and waned between enforcement and comparative openness, with ambitious electeds (are there any other kind?) either making genuine efforts to improve things, or looking for the nearest camera to show their bona fides.

I’m always struck when some politician says, “We are better than this.” No, not really. Compassion and tolerance hasn’t always been our strong suit with immigrants—even those we let in. We have marginalized them, limited their political power, interred them, even assaulted and occasionally murdered them. Our Town Halls and County Clerk’s offices are filled with property deeds that restrict ownership and occupancy to only those “of the Caucasian Race.” We had an entire political party (the Know-Nothings) built on opposition to Catholicism and immigration, particularly by the Irish and Germans. Our scapegoating of immigrants for every possible social dysfunction did not begin with the current occupant of the White House and will not end with his leaving it. When it comes to the mortal dangers to our culture and our very way of life posed by a starving eight-year old who doesn’t speak much English, hysteria is always in season.

What we have not done is fix anything. We have, at times, tried hard. Ronald Reagan and Congress made creditable efforts in 1986, and accomplished a great deal, but the weaknesses of the Immigration Reform and Control Act are the things held up by hardliners as reasons to get even more stringent, while the substantial achievements of it are largely forgotten.

The reality is we have not made our borders impermeable, or settled on what a policy for short- and long-term legal immigration should be, or decided who can become citizens, or even determined how much desperation is enough desperation that it merits possible asylum. We have come up with some terrific slogans and some really scary television ads, but where we are right now, for better or (mostly) worse, is the sum of our choices.

Failure is not inevitable. The issues are complicated but not insuperable. To an extent, you can blame both sides for refusing to accept the validity of contrary arguments. Many immigration advocates don’t grasp the potential burdens illegals place on already strained social services. They are so wound up in what they see as a humanitarian crisis that they don’t realize it comes at the price of support for legal immigration. On the other side of the equation, many immigration hawks have shown that they aren’t really for comprehensive reform because they aren’t really for the implications of comprehensive enforcement. They want punishment of the immigrant at no cost to our society. We could couple a generous guest worker program with the application of E-Verify at virtually every level of employment, and make the fines so punitive that anyone would think multiple times before employing any illegals. We don’t, because the businesses that rely on them as seasonal workers, day-laborers, and others doing disgusting jobs for low pay would suffer, and those businesses write some mighty big checks. We could prevent foreigners from competing against “our kids” for spots at the best colleges and universities by limiting or getting rid of student visas. But then you would be turning back highly qualified students who can pay full tuition. Same for hi-tech and academic jobs—we could stop issuing H-B1 visas, and then lose some of the best minds in the world who have contributed to discovery, innovation, and economic growth. And all of that is without taking into account the costs of possible retaliation from the countries we select as targets. Pick your issue, and there is always a tradeoff. The sour stalemate we live in is a reflection of our unwillingness to face that.

This isn’t to say there aren’t plenty of people of good will who are willing to make serious efforts at reform—the problem is that they aren’t really sure whom to trust if they put themselves out there. Immigration is the true third rail of American politics, and if you want to see a naked illustration of how it makes the courageous cautious and the weak and ambitious duplicitous, go back six years to the Senate Gang of Eight. In 2012, Senators Schumer, McCain, Flake, Rubio, Durban, Bennet of Colorado, Menendez, and Graham put everything on the table and came up with a far-reaching compromise. The Senate passed a bill based on that agreement, and there it stalled. First John Boehner, invoking the “Hastert Rule,” refused even to take it up in the House. Then, Marco Rubio, fearful about damaging his own Presidential hopes, sold out his partners by backing a Senate amendment by John Cornyn that McCain called a “poison pill.”

What we learned from the Gang of Eight experience is even more true today: It isn’t that we can’t come up with reasonable solutions; it’s that too many politicians profit from the status quo of no deal. They want the issue, but not the resolution.

There is an old adage to the effect that there are three kinds of people: Those who do; those who complain, but do; and those who just complain. In the immigration debate, where seemingly everyone has a beef, no one just “does,” so we have to be able to identify, and back, the “complains and does” over the “just complains.”

Which one is Trump? I wish I knew, because Trump’s intransigence, his inflammatory rhetoric, and his casual cruelties make him the perfect guy for a “Nixon to China” moment. But I don’t know that he’s willing. Remember that Trump’s approach is purposeful—there’s the tactical choice of intimidation and the strategic choice of supporting his reelection campaign, which revolves around motivating his base.

What is clear is that if Trump doesn’t want to come to a reasonable, comprehensive agreement, there is no way a GOP-controlled Senate and a relatively narrow Democratic House majority can possibly make him. So, the question becomes, how do you incentivize Trump to come to the table? For a serious, bipartisan effort passed by both the House and Senate and signed by him, I expect him to demand a price. He’s made a career and a fortune trading other people’s money for personal gain, and I suspect he’s fine with trading other people’s misfortune in the same way.

Can we afford to pay his price, if he’s even selling? It should be blatantly obvious from this synthetic shut-down crisis that the Wall is largely an incredibly costly symbol, a branding opportunity. You could give Trump $50 billion and an unlimited supply of crocodiles to fill the moats, but if he’s really going to let Rush, Laura Ingraham, and Ann Coulter write immigration policy, there’s no deal to be made.

Maybe it just can’t be done with Trump. That leaves us where we are now…no coherent policies, millions of illegals here, relatively porous borders, no clarity on DACA or a pathway to citizenship, rhetoric that angers some of our allies, and a blind eye to humanitarian issues that further damages our reputation. Something horrible for everyone.

Of course, we Czars (the voters) could get disgusted enough to tell our politicians that we understand that the enemy of the good is the perfect, that we are tired of this mess and this mindless bickering, and that we expect them to stop complaining and start doing.

Now, that’s a completely crazy idea.