by Claire Chambers

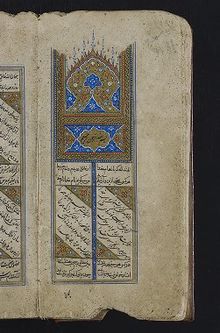

Ghazal poetry is an intimate and relatively short lyric form of verse from the Middle East and South Asia. The form thrives in such languages as Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and now English. Like the Western ode, these poems are often addressed to a love object. Influenced by ecstatic Sufi Islam, the ghazal’s subject matter concerns desire for another person and, figuratively, love for the Divine.

Indeed, a mixture of sacred, profane, romantic, and melancholic elements are frequently stitched into the ghazal’s poetic fabric. Many ghazals revolve around the theme of lovers’ separation. This topic also functions as an image for the Muslim worshipper’s longing for Allah. In doing so, the ghazal draws comparisons with seventeenth-century metaphysical poetry. Like ghazalists, John Donne would ostensibly write about love for a woman but also shadow forth devotion to God.

Sound, rhyme, repetition, and rhythm come to the forefront in this form. This makes it unsurprising that many ghazals have been turned into songs. For instance, during the course of his illustrious poetic career, Mohammad (‘Allama’) Iqbal (1877–1938) wrote dozens of ghazals. Some of these poems have been set to music. They were sung by popular South Asian musicians including the late Mehdi Hassan and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, as well as contemporary singers Lata Mangeshkar and Sanam Marvi. I also think of the famous playback singers Noor Jehan’s and Nayyara Noor’s renditions of the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911–1984). This crossover often surprises Westerners: it’s as though Carol Ann Duffy’s poems were being sung by Rihanna! Read more »

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).