by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning. Read more »

The language of light is compelling. The suggestions of light at daybreak are vastly different from twilight or starlight, the light of a firefly is not the same as that of embers or cat eyes, and light through a sapphire ring or a stained glass window is not the same as light through the red siren of an emergency vehicle or through rice-paper lanterns at a festival. It matters to writers if the image they are crafting of light is flickering or glowing, glaring or fading, shimmering or dappled. A writer friend once commented on light as a recurring motif in my poetry, and told me that I’d enjoy her son’s work as a light-artist for theater. The thought struck me that light in a theater has a great hypnotic, silent power; it commands and manipulates not only where the audience’s attention must be held or shifted, how much of the scene is to be revealed or concealed, but also negotiates the many emotive subtleties and changes of mood. The same goes for cinema, photography, and other visual arts. Light almost always accompanies meaning. Read more »

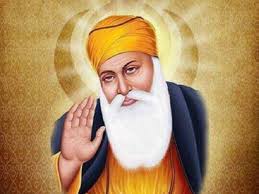

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore.

A few tall, dreamy-eyed Sikh men were on my plane to Lahore.

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).

“I’m on a roadside perch,” writes Ghalib in a letter, “lounging on a takht, enjoying the sunshine, writing this letter. The weather is cold…,” he continues, as he does in most letters, with a ticklish observation or a humble admission ending on a philosophical note, a comment tinged with great sadness or a remark of wild irreverence fastened to a mystic moment. These are fragments recognized in Urdu as literary gems because they were penned by a genius, but to those of us hungry for the short-lived world that shaped classical Urdu, those distanced from that world in time and place, Ghalib’s letters chronicle what is arguably the height of Urdu’s efflorescence as well as its most critical transitions as an elite culture that found itself wedged between empires (the Mughal and the British), and eventually, many decades after Ghalib’s death, between two countries (Pakistan and India).