by John Hartley

“To err is human,” observed the poet, Alexander Pope. Yet, why do we consciously choose to err from right action against our better judgement? Anyone who has tried to follow a diet or maintain a strict exercise regime will understand what can sometimes feel like an inner battle. Yet why do we stray from virtue, choosing paths we know will lead to inevitable suffering? Force of habit? Addiction? Weakness of will?

This crisis of moral choice lies at the heart of Western philosophy, as the Ancients crafted their doctrines to explain why individuals often fail to realize their good intentions. “For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out.” Observed St Paul, “For what I do is not the good I want to do; no, the evil I do not want to do–this I keep on doing.”

Akrasia in ancient thought

Homer’s Iliad paints a poignant portrait of humanity, ensnared in a cycle of necessity. This relentless loop can only be broken by wisdom and self-knowledge, encapsulated in the Delphic maxim “know thyself.” Socrates, however, argued that true knowledge of the good naturally precludes evil actions (If you really know what is right you will not do wrong!) He contends that misdeeds arise not from a willful defiance of the good but from flawed moral judgment—a tragic aberration, mistaking evil for good in the heat of the moment.

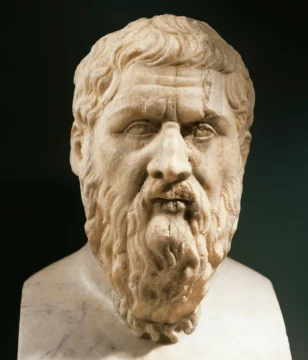

Plato linked wisdom and necessity to the duality of good and evil. He envisions self-realization and ordered integration as pathways to the good (inefficiency and unrealized potential signify malevolence). For Plato, good and evil are not external forces but internal currents: one flowing with love and altruism, the other emanating greed, envy, and malice.

The ascent to goodness, according to Plato, hinges on self-mastery and moral transformation, guiding one’s life towards the ideal form of goodness. Stoicism, of course, has experienced something of a resurgence of late, owing to Gen Z influences advocating extreme self discipline and heightened personal responsibility.

Evil, Plato posits, springs from ignorance, and moral knowledge is attained through the purification of the soul. Virtue, therefore, becomes the hallmark of the ideal citizen of the ideal society, embodied through wisdom, courage, sobriety, and justice. Sobriety, or continence, is particularly crucial for navigating the treacherous waters of moral choice.

Aristotle, Plato’s divergent pupil, reshaped this moral framework, asserting that morality is anchored in voluntary acts, placing the onus squarely on individual moral choice. We are the architects of our destiny, sculpted by our actions. Addressing the crisis of moral choice, Aristotle identifies the ‘weak-willed’ man—one who knows the good yet falters into evil. This is the Man who loses his head in battle or panics under pressure.

This phenomenon, akrasia, describes a moral dissonance where the individual’s knowledge of the good becomes momentarily obscured. Despite his love for the good, the weak-willed man is ensnared by ego, rendering him incapable of moral wholeness. Aristotle here, is linking fixation upon the self as the inability to see the bigger picture, as the source of moral failure.

Augustine and the divided will

With penetrating insight into the human condition, St. Paul attributes the crisis of moral choice to the problem of the divided self—the inability to fulfill good, intended resolutions. Paul approaches the Rabbinic notion of yeser—man’s inherent potential that drives him towards both good and evil—as the genesis of all moral wrongdoing. Intriguingly, while yeser prompts man to do evil, it paradoxically also fuels life’s essential pursuits: marriage, procreation, and nation-building.

Paul’s analysis of moral evil in Romans 7 reveals how indwelling sin thwarts the fulfilment of the good in which one’s inmost self delights. For Paul, emulation of Christ is the sole refuge from our baser tendencies, with the eradication of free will reducing humanity to mere automatons. He famously exhorted Christians to “crucify the flesh” to combat its proclivity for succumbing to lower impulses.

Augustine of Hippo’s philosophical journey was marked by his personal attraction to evil. Augustine climbed into a neighbor’s orchard and stripped a pear tree of its fruit “not to eat the fruit ourselves, but simply to destroy it.” He admitted that there were better pears to eat in their own gardens.

This attraction to evil and innate desire to transgress boundaries is a theme echoed in literature through characters like Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Such actions suggest that humans possess a deep-seated desire to rebel against the moral order.

Building on Platonism, Augustine proposed that true happiness—or eudaemonia—is achieved when one loves and possesses the highest good. Contra Plato, the four cardinal virtues are actually doctrines of love and humility, placing agape, or selfless love of God, as the pinnacle. Unlike Plato’s ‘self-knowledge’, Augustine viewed knowledge and love of God as the ultimate means to achieving true goodness. He posited that virtues pursued without this divine inspiration ultimately invert to mere pride, so that all good intentions, outside of this end, ultimately terminate in evil.

Augustine’s contemplation on human frailty revealed that even when one recognizes the supreme good, the capacity to act on it remains elusive, hampered by a blinded and fettered will. This realization, that virtue is not innate but divinely infused, shaped his belief that humanity must rely on God’s grace to achieve moral goodness.

In refining his thoughts on the crisis of moral choice, Augustine distinguished between his new will aligned with divine aspirations and his old, rebellious nature. This nuanced understanding of human will versus nature underscores that true moral agency requires voluntary action. His interpretation of Paul’s struggles with sin led to the profound conclusion encapsulated in his maxim: “Love, and do as you will.” Under divine grace, he argued, the will aligned with God’s love and forgiveness can only lead to right moral action.

Hence, to return to Pope, “To err is Human; to Forgive, Divine”