by Daniel Shotkin

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

This week marks one year since Affirmative Action was repealed by the Supreme Court. The landmark ruling was a watershed moment in how we think of race and social mobility in the United States. But for high schoolers, the crux of the case lies somewhere else entirely.

Like many others, getting admission to a ‘top college’ is high on my bucket list. So when cable news analysts and op-ed columnists were arguing the facts of the case, my eyes turned elsewhere. For me, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard was about the troves of confidential admissions documents being publicly released as evidence. What these documents showed has changed my view on college admissions.

What does a college look for in a student? Boy, would I like to know.

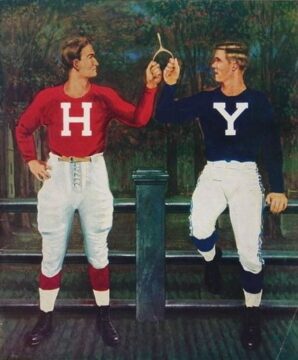

Consulting college admissions pages for a straightforward answer feels like visiting the Oracle of Delphi. Yale’s admissions website describes Yale students as “those with a zest to stretch the limits of their talents, and those with an outstanding public motivation.” Columbia writes that they look for “intellect, curiosity, and dynamism that are the hallmarks of the Columbia student body.” What these soul-searching terms fail to describe is what a ‘zest to stretch the limits’ translates to on paper. Harvard is a bit more honest, though—“there is no formula for gaining admission.”

What unites these colleges is that they all enforce holistic review in admissions—considering all parts of an application to paint a full picture of the student. In doing so, colleges acknowledge all sorts of factors like income level, parent education level, and extenuating circumstances. On paper, recognizing these factors levels the playing field for both disadvantaged and privileged students. But the information disclosed in the Affirmative Action case reveals what many of us have long suspected—that top colleges use holistic admissions to maintain an elite.

Among the materials released by Harvard was a list of over 120 factors the college looks for in a student. Turns out there is a formula for admission and it’s pretty well defined, just not for those applying. The college considers factors like being the first to receive higher education, the median income of your neighborhood, or the amount of AP tests your high school offers—all factors that lead to disadvantages that Harvard acknowledges as part of their holistic review. But crucially, just as Harvard gives disadvantaged students a leg up, it favors students from ultra-rich families on an even greater scale.

If we take the 2014 Harvard admissions season, for instance, the overall acceptance rate hovered at around 6%—but not for everyone. Two of the 120 factors published by Harvard resulted in astonishingly higher acceptance rates. For students with ‘lineage’—whether or not your parents attended the college—the admissions rate grew to 33%. Those on the dean’s list—a confidential list of students often related to top donors—saw a 42% admissions rate. And though these facts may seem insignificant on their own, they matter for a couple of key reasons.

The dean’s list might seem like a demographic footnote, but more than 10% of Harvard’s class of 2019 was represented on file. If lineage on its own may seem like a relatively inconspicuous factor, it grows more questionable when considering that lineage students are likely from ultra-wealthy families—roughly 31 percent of students who had parents attend Harvard reported a family income of $500,000 or more. And just because lineage and dean’s list students come from wealthier families does not mean they are more qualified than the rest of the pile. Duke economist Peter S. Arcidiacono, a witness on the Affirmative Action case, found that 75% of white students admitted based on legacy status, athletic ability, or presence on the dean’s list would be rejected were it not for those factors.

These practices aren’t unique to Harvard. A study by Opportunity Insights, a Harvard-based inequality research group, examined data from the so-called ‘Ivy-plus’ group of colleges—the Ivy League, the University of Chicago, Duke, MIT, and Stanford. Among these colleges, students from high-income families are more than twice as likely to be admitted compared to those with similar test scores from low or middle-income families. If that’s not enough, one in six Ivy League students has a parent in the top 1% of income.

A common refrain among defenders of the admissions status quo is that elite colleges are the exception, not the norm. Such arguments often posit that an Ivy League education isn’t necessarily a better education and that students are deluded by the name-brand attraction of such schools.

To an extent, they’re right. Attending an Ivy instead of a top 9 public university does not meaningfully increase graduates’ income, on average. Likewise, at top public universities, applicants with high-income parents receive no advantage compared to other applicants.

But those who attend colleges in the Ivy League have an undeniably outsized role in society. 12 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs and a quarter of U.S. senators hail from the Ivy League. The same can be said about 13% of the top 1% of earners. America’s political, economic, and intellectual elite disproportionately comes from elite colleges, so it’s natural that many high schoolers (and, more often than not, their parents) claw at the idea of landing a spot. But at the end of the day, the admissions system that decides who gets a piece of the pie systematically favors those who already have a slice.

So how can we change the system to truly level the playing field?

Proponents of holistic admissions would tell you that introducing a more holistic review is the way forward. I.e., if the holistic scales are tipped too much in favor of students from wealthy families, the solution is to provide even more special considerations for those with fewer resources. This is why abbreviations like FGLI (first-generation low-income) now proliferate college counseling websites and forums. Likewise, colleges now partner with programs like QuestBridge that provide admissions officers with a steady feed of high-achieving low-income students. As someone who will likely benefit from these efforts, I acknowledge that the actions are well-intentioned and provide fantastic opportunities for underprivileged students. But at the end of the day, they do not fix the underlying problem with college admissions. Sole reliance on holistic admissions will always allow colleges to put a lucrative student body (whether it be in donations or P.R. points) over a qualified student body.

If we truly want a meritocratic system of admissions, we need to stop trying to reinvent the wheel. Adding more caveats to holistic admissions won’t fix anything—if anything, it just makes the system more opaque. Thankfully, there is already a system of higher education admissions that works—just look across the pond.

Of the 26 countries that rank higher than the United States on the global social mobility index, not one uses a higher education admissions system based on holistic review. The trend globally is simple—standardized testing. The matura, selectividad, arbitur, A-levels, gaokao—call it what you want—standardized tests are the norm globally. Universities publicly state a minimum score that, either alone or together with grades, would guarantee admissions. Such a system prevents institutional bias, provides transparency, and rewards objectivity—all factors notably absent from the smoke and mirrors of holistic review.

No, I’m not arguing for complete dependence on a single test that determines a student’s entire life. And no, I’m not someone that gets any pleasure out of 3 hour SATs. However, the admissions pendulum needs to swing away from the opacity of holistic review and toward greater reliance on standardized testing. Doing so would foster greater understanding between students and colleges, level the playing field for the 1% and the 99%, and ensure that institutional biases play no role in deciding who deserves a seat at the table.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.