by Adele A. Wilby

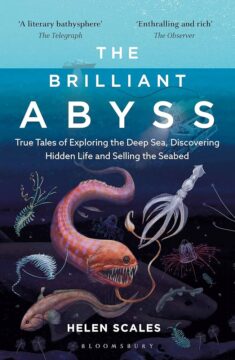

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

From the outset the breadth of Scales’ knowledge of the ocean is apparent, when, in Part One, she suggests we ‘let’ go’ of our customary understanding of time and she takes us back to the ‘backstory’ of the ocean millions, even billions, of years ago. Evocative prose render just how the pre-historic ocean floor of the Palaezoic era was swarming with trilobites of all shapes and sizes. Twenty-five thousand species of trilobites are known to have existed, yet despite their abundance not a single living trilobite can be found in today’s ocean: they went extinct. She uses this example to highlight that abundance is no guarantee of the survival of a species in the ocean.

Scales continues to narrate, how, over the course of the history of the planet, catastrophic natural events have periodically decimated ocean life. Fewer than one in ten ocean species survived the Permian extinction event that ended the Palaeozoic era 250 million years ago and marked the beginning of the Mesozoic period. It is challenging for us to imagine the ocean swarming with reptiles during the Mesozoic era, yet Scales provides numerous examples of those species. Nevertheless, over the millennia of the Mesozoic era some reptiles also went extinct while others continued to evolve. In today’s ocean, the only living reptiles are sea turtles and sea snakes.

Although extinctions and changes in the ocean have been a feature of the history of Earth, recovery over time has been possible and evolution progressed, demonstrating that life is complex and shapes biodiversity in different forms and can deal with new challenges. But the past fifty years of the Anthropocene, human activity, Scales argues, is of a different order and has become the major influencer for global change, and in Part Two she provides abundant evidence of the devastating impact of this on the ocean. For example, climate change, she points out, is threatening the populations of that most beloved of penguins, the emperor on the Antarctic ice.

Since the 1950s, scientists have been aware of a colony of emperors at Halley Bay at the Antarctic, and for sixty years the sea ice remained stable, and the emperors were able to breed and thrive. That was all to change in 2016 when an unusual storm whipped along the edges of the ice shelf and broke apart the ice. The ice collapsed and with it the young chicks drowned. Over recent times, the ice has steadily declined with its impact on emperor breeding patterns. As the climate heats and sea ice vanishes, the fringe ice is shrinking, and, according to Scales, threatening a potential for an 80 per cent crash in the emperor colonies. The best chance for the emperors in the future, in her view, lies with a reduction in human-made carbon emissions that will forestall global warming and the melting of the ice.

Human activity in the form of overfishing also has a major impact on ocean life. Human beings have always fished the seas and will continue to do so into the future, but modern fishing methods, Scales shows us, are a real cause for concern for its impact on marine life. In 45 percent of the ocean, longline fishing, a method where a long nylon line of twenty-eight miles or more with short branches, is shot into the sea and fish such as tuna, marlin and swordfish are easily snared. Likewise, the shark populations are threatened by longline fishing. Sharks have a long gestation period and are unable to produce offspring and replenish their numbers before they are snared on longlines. The Greenland shark, a species that starts reproducing at the age one hundred years, is a case in point. But the sharks have been given some reprieve. In 1993 the US government introduced a recovery plan to halt the ruthless overexploitation of sharks in the Atlantic, and since then the decline in the hammerhead sharks has levelled off and the population of tiger and great whites have also stabilised. Scales does acknowledge however, that there will be no swift return for the species that spend decades maturing and producing offspring.

Government intervention is a possible way to regulate fishing practices and constrain the loss of marine life, but dealing with toxic substances in the ocean is a different matter: separating toxins from water seems an impossible task, and once in the water, as Scales reveals, they enter the bodies of marine species. Artificial chemicals such as PCB form a toxic soup on part of the ocean. PCB and other pollutants are fat soluble, and this makes mammals with large layers of blubber, such as whales, seals, porpoises and narwhals particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of PCB, impacting on the animals’ immune system and brain function and disrupting hormones and causing infertility, with obvious long term devastating implications for the populations of the species. Plastic debris is also another threat to marine life. According to Scales there has been a recent estimation of between 82 to 358 trillion microplastic particles in the ocean. Thousands of ocean species have been found with microplastic inside their bodies, and many of these species are part of the human food chain.

Scales provides ample evidence of the tragic impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life for us to be concerned for the future of the ocean with implications also for human beings. In her exposition she has introduced us to the mysterious underwater lives and environments of many fascinating marine life forms and the threat posed to them by reckless human behaviour and the desire for profiting from marine life. Such is the scale of the overexploitation and destruction that the very existence of species and the ecosystems they inhabit are faced with devastation, even extinction. In Part Three however, the central purpose of her book, Scales manages to temper her deep concern with cautious optimism of the future for the ocean.

In the chapter ‘Restoring Seas’ she cites the case of bluefin tuna, historically commercially hunted by human beings bringing them in many areas of the ocean to the brink of extinction and in desperate need of protection. Only when the International Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT) finally agreed to cut the quota on fishing bluefin tuna have the fish showed signs of recovery. But even then, Scales is cautious in her optimism over the recovery of the tuna. While the eastern Atlantic bluefin tuna appear to be on the rise, the western population of tuna in the Gulf of Mexico have been in decline over the past four decades. In the long term it appears the future of tuna is subject to the vicissitudes of human activity in implementing policies and behaviour that will allow for the restoration of the tuna and secure a future for them.

Some success has been achieved in protecting sea life by identifying areas of the ocean and designating them as marine reserves. New Zealand, for example, was the first to institute a new marine reserve and its success became a source of inspiration for a scuba diver from the Isle of Arran in Scotland, resulting ultimately in Lamlash Bay in Scotland being designated a marine reserve. In these areas fish have a chance to grow bigger, reproduce offspring and live longer, but the protected areas are only a miniscule part of the ocean. Of course, fish know no boundaries and will swim out of the reserves, but still the population outside the reserve will have increased. But Scales’ optimism is again tempered when she warns that we should not be lured into a false sense of security by these measures, especially when other detrimental actions in the ocean are taking place and are possible in the future, and here she points to deep-sea mining.

The insatiable aspiration of human beings to discover new sources of precious metals required to sustain the global economy and our lifestyles into the future, drives deep-sea mining. Polymetallic nodules, nodules with millions of years of age, containing valuable and highly sort after elements like cobalt, nickel and other rare metals are particularly vulnerable to being mined. But these ancient nodules also support diverse ecosystems which are only just beginning to be understood. Scales further reveals there are many known geological structures in the ocean and more to be identified and their significance to the ocean and life on the planet yet to be fully appreciated, all threatened by ocean mining. Nevertheless, she welcomes that some progress has been made in forestalling the extent of mining. Many countries have supported a moratorium, with some countries, such as France, calling for a full ban on ocean mining altogether. Scales is hopeful that as more and more knowledge is revealed about the consequences of such an industry on the ocean, people will be convinced of the importance of halting the practice. Still, it appears now that the best we can hope for in the future is that at least ‘swathes’ of the ocean will escape the devastation caused by ocean mining.

Scales continues in Part Three to set out the problems facing ocean forests and the coral and highlights measures taken to address the existential threats to these areas of ocean life, but her optimism is frequently neutralised when she points out the possibility of the consequences of what is likely to happen if measures are poorly implemented or neglected.

In the final chapter, ‘Living in the Future Ocean’ she ultimately provides us with the broad scope of her ideas of how to create a better future for the Anthropocene ocean and how people will also live with it. As she says, billions of people living on coastal areas are being impacted by rising sea levels, a cause of great concern to many governments. Thus, in response, the world’s first floating city is no longer in the realm of fantasy but has become a feasible project. Faced with rising sea levels consequent to global warming, the Maldives government is in consultation with architects for the construction of a floating city, with a possibility of it being in place by 2027.

Of her many suggestions for protecting the ocean, Scales also argues for ethically and sustainable fishing with strict limits on industrial fishing and protection for habitats and species, raising contested arguments around the concepts of ‘ethically’ and ‘sustainability’ insofar as ocean life is concerned. Looking further into the future, she sees some hope for the ocean in science and technology. Companies are investing in laboratory grown seafood, but the success of such a project again depends on human response to the products.

The importance of reducing our use of plastics and lobbying and pushing back against the oil and fossil industry’s involvement in the production of plastics are collective principles expressed by environmental activists, and Scales also advocates such practices. She also encourages people to engage in environmental activism in schools, offices, everywhere to secure a better future for the ocean. Likewise, she emphasises the importance of grassroots activity for change and as an example she shows how women are making a significant contribution in the way seafood is produced and consumed in the form of promoting seaweed consumption and in managing lobster farms.

Scales’ book reveals to us the history, beauty and complexity of the ocean and the drastic impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life. What becomes apparent throughout the book is the complexity, extensive and multilayered task that restoring and maintaining oceans requires. Nevertheless, she retains some optimism that there will be a growing awareness amongst human beings of the importance of the ocean which will encourage people to act to protect and create a better future for the ocean and therefore life on the planet. Her book makes an important contribution towards creating that awareness.