by David Kordahl

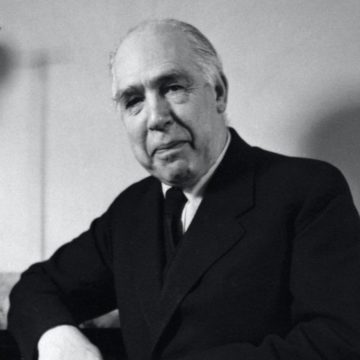

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when the picture was taken. But public memory is fickle, and today only the man on the right is still recognizable to most people.

The photograph beside this text shows two men standing side by side, both scientific celebrities, both Nobel prizewinners, both of them well-known and well-loved by the American public in 1932, when the picture was taken. But public memory is fickle, and today only the man on the right is still recognizable to most people.

Albert Einstein, Time Magazine’s “Man of the Century,” the father of special and general relativity, has a place in science that remains secure, regardless of what one thinks of his life as a whole. Despite activist efforts at demystification, Einstein the scientist is unblemished by any misgivings about his personal life or political activities. Robert A. Millikan, the bow-tied man on the left, is far less secure. The posthumous charges against Millikan have been against his scientific integrity and his political sympathies, and his detractors have made headway.

In 2020, Pomona College changed the name of their Robert A. Millikan Laboratory, noting Millikan’s “history of eugenics promotion,” along with his purported sexism and racism. In 2021, the California Institute of Technology, the institution that Millikan spent decades building, followed suit, renaming Millikan Hall as Caltech Hall, and discontinuing the Millikan Medal, previously the Institute’s highest honor. Citing Caltech’s precedent, the American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) renamed its own Millikan Medal later that same year.

Since I spend most of my time teaching physics, and since I am myself a member of the AAPT, it was the last of these name changes that rankled me the most. These allegations bothered me because I suspected that they weren’t quite fair. Read more »

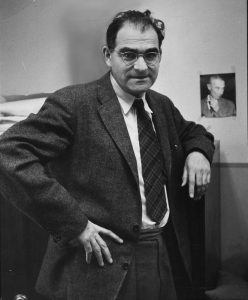

Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.

Victor Weisskopf (Viki to his friends) emigrated to the United States in the 1930s as part of the windfall of Jewish European emigre physicists which the country inherited thanks to Adolf Hitler. In many ways Weisskopf’s story was typical of his generation’s: born to well-to-do parents in Vienna at the turn of the century, educated in the best centers of theoretical physics – Göttingen, Zurich and Copenhagen – where he learnt quantum mechanics from masters like Wolfgang Pauli, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr, and finally escaping the growing tentacles of fascism to make a home for himself in the United States where he flourished, first at Rochester and then at MIT. He worked at Los Alamos on the bomb, then campaigned against it as well as against the growing tide of red-baiting in the United States. A beloved teacher and researcher, he was also the first director-general of CERN, a laboratory which continues to work at the forefront of particle physics and rack up honors.