by David Kordahl

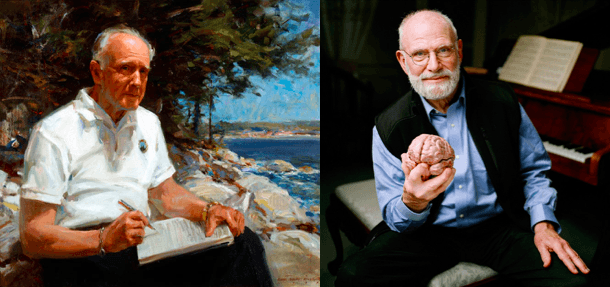

The physicist Philip W. Anderson, winner of the Nobel Prize in 1977, has lingered in the broader scientific imagination for two main reasons—reasons, depending on your vantage, that cast him either as a hero, or as a villain.

The heroic Anderson is the author of “More Is Different,” the 1972 essay that wittily dismisses the idea that the laws of physics governing the microscopic constituents of matter are by themselves enough to capture the full richness of the world. His vision of science as a “seamless web” of interconnections led to his becoming one of the public faces of so-called “complexity science,” and a founding member of the Santa Fe Institute.

The villainous Anderson is remembered for taking this position—the position that the low-level laws of physics do not exhaust fundamental physics—in front of Congress. Anderson’s tart exchanges with Steven Weinberg before the Senate debating the merits of the Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) begin a new biography, A Mind Over Matter: Philip Anderson and the Physics of the Very Many, by Andrew Zangwill. When the SSC was canceled, Anderson, who argued that the funds would be better spent on a wider variety of projects, became a target of physicists’ ire, despite his lack of any significant political influence. (Weinberg’s last book of essays, which I reviewed, extensively discussed the politics of the SSC.)

But Anderson, who died just last year, was much more than just a hero or villain. A Mind Over Matter makes the case that Anderson was “one of the of the most accomplished and influential physicists of the twentieth century.” In presenting the evidence, Zangwill, who is himself a notable physicist, gives us a tour of condensed-matter physics, the science that deals with the properties of materials not atom-by-atom but roughly 1023 particles at a time, a subject where Anderson’s influence continues on. Read more »

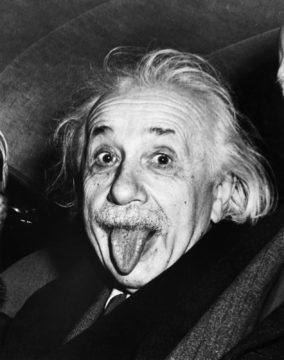

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

Considered the epitome of genius, Albert Einstein appears like a wellspring of intellect gushing forth fully formed from the ground, without precedents or process. There was little in his lineage to suggest genius; his parents Hermann and Pauline, while having a pronounced aptitude for mathematics and music, gave no inkling of the off-scale progeny they would bring forth. His career itself is now the stuff of legend. In 1905, while working on physics almost as a side-project while sustaining a day job as technical patent clerk, third class, at the patent office in Bern, he published five papers that revolutionized physics and can only be compared to Isaac Newton’s burst of high creativity as he sought refuge from the plague. Among these were papers heralding his famous equation, E=mc^2, along with ones describing special relativity, Brownian motion and the basis of the photoelectric effect that cemented the particle nature of light. In one of history’s ironic episodes, it was the photoelectric effect paper rather than the one on special relativity that Einstein himself called revolutionary and that won him the 1922 Nobel Prize in physics.

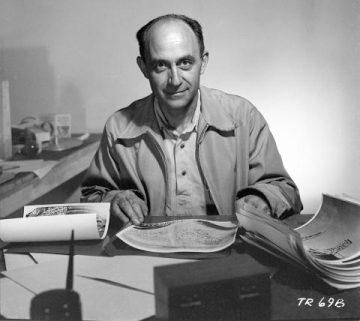

In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist.

In November 1918, a 17-year-student from Rome sat for the entrance examination of the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa, Italy’s most prestigious science institution. Students applying to the institute had to write an essay on a topic that the examiners picked. The topics were usually quite general, so the students had considerable leeway. Most students wrote about well-known subjects that they had already learnt about in high school. But this student was different. The title of the topic he had been given was “Characteristics of Sound”, and instead of stating basic facts about sound, he “set forth the partial differential equation of a vibrating rod and solved it using Fourier analysis, finding the eigenvalues and eigenfrequencies. The entire essay continued on this level which would have been creditable for a doctoral examination.” The man writing these words was the 17-year-old’s future student, friend and Nobel laureate, Emilio Segre. The student was Enrico Fermi. The examiner was so startled by the originality and sophistication of Fermi’s analysis that he broke precedent and invited the boy to meet him in his office, partly to make sure that the essay had not been plagiarized. After convincing himself that Enrico had done the work himself, the examiner congratulated him and predicted that he would become an important scientist. There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.