by Ashutosh Jogalekar (Warning: Spoilers ahead)

Reviewing biopics is tricky. On one hand, if you are someone informed about the facts, it’s easy to bring a scalpel and dissect every fact and character in minute detail, an exercise that will almost always lead to a critical and often negative view of a film. On the other hand, knowing that a movie is a medium of expression defined a certain way, one has to allow for creative license and some convenient omissions and embellishments that would be unforgivable in a documentary or historically accurate drama. Thus, the best way to review biopics in my opinion is a middle path, making allowance for artistic interpretations and changes of fact while still holding the movie maker up to high standards in terms of making sure that these changes don’t fundamentally distort the soul of the narrative.

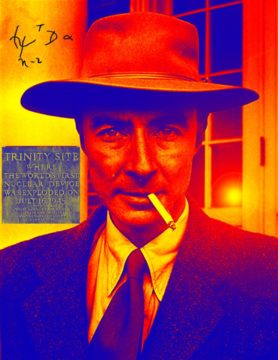

I went into Christopher Nolan’s 3-hour extravaganza keeping this middle ground in mind. Having just written an eight-part series about Oppenheimer and been familiar with his life and work for a fairly long time, I approached the film with fairly high expectations. And I have to say that I was impressed. If one simple metric of a high-quality film is its ability to keep you glued to your seat for 3 hours, “Oppenheimer” delivers in spades. Much of this effect comes from Nolan’s judiciously assembled direction and from outstanding performances by key characters that keep the audience riveted. “Oppenheimer” is an Oliver Stone-like jigsaw puzzle, breathlessly switching between timelines, black and white scenes and pithy character lines interspersed with artistic imagery of crackling jolts of electricity, the shimmer of particles and waves and imagined operatic scenes of stars that signify the deep scientific reality behind our everyday world. Key aspects of the Trinity test like the assembly of the bomb and the details of the fireball are accurately rendered. But first and foremost, it is a drama about J. Robert Oppenheimer. Read more »