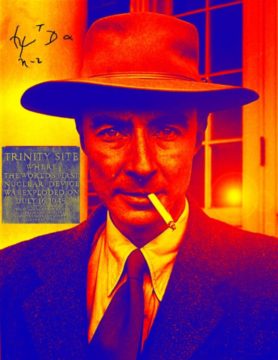

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

This is the second in a series of posts about J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life and times. All the others can be found here.

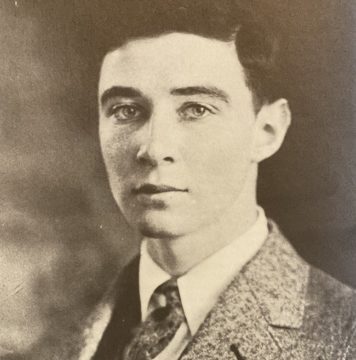

In the fall of 1922, after the New Mexico sojourn had strengthened his body and mind, Oppenheimer entered Harvard with an insatiable appetite for knowledge; in the words of a friend, “like a Goth looting Rome”. He wore his clothes on a spare frame – he weighed no more than 120 pounds at any time during his life – and had striking blue eyes. Harvard required its students to take four classes every semester for a standard graduation schedule. Robert would routinely take six classes every semester and audit a few more. Nor were these easy classes; a typical semester might include, in addition to classes in mathematics, chemistry and physics, ones in French literature and poetry, English history and moral philosophy.

The best window we have into Oppenheimer’s personality during his time at Harvard comes from the collection of his letters during this time edited by Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner. They are mostly addressed to his Ethical Culture School teacher, Herbert Smith, and to his friends Paul Horgan and Francis Fergusson. Fergusson and Horgan were both from New Mexico where Robert had met them during his earlier trip. Horgan was to become an eminent historian and novelist who would win the Pulitzer Prize twice; Fergusson who departed Harvard soon as a Rhodes Scholar became an important literary and theater critic. They were to be Oppenheimer’s best friends at Harvard.

The letters to Fergusson, Horgan and Smith are fascinating and provide penetrating insights into the young scholar’s scientific, literary and emotional development. In them Oppenheimer exhibits some of the traits that he was to become well known for later; these include a prodigious diversity of reading and knowledge and a tendency to dramatize things. Also, most of the letters are about literature rather than science, which indicates that Oppenheimer had still not set his heart on becoming a scientist. He also regularly wrote poetry that he tried to get published in various sources.

Oppenheimer’s literary flourishes and baroque exaggeration are perhaps the most important aspects of the letters. They show a young man who was both brilliant and unafraid to show his erudition as well as insecure and given to bouts of irony and self-pity; in one letter to Smith he describes his work as “frantic, bad, and graded A”. A typical excerpt of his style comes from a letter written by the 18-year-old to Horgan on October 6, 1923:

“This note, hélas, has got to be as short and unrhetorical as my inebriate soul and the explosive nature of my felicitations can conspire to make it. I mean, beloved, that I would like, if I had time and power, to answer your splendid epic with one not incomparable to it, and match the intricate patterns of of your quotations, allusions, epigrams, poetics, and flattery in my reply. But it is a tragic and overwhelming truism that my paltry successes do not come without assiduity and labor; that the Artzibasheffs I conquer demand a pretentious pertinacity and patience; that I am, quae cum ita sint, hysterically engaged in keeping soul and body from complete disintegration and decrepitude; and that, accordingly, I shall be unable to fabricate a masterpiece fit to stand beside, say, your “Now he is on the ocean.”

Perhaps the most revealing letter is one written to Herbert Smith during the winter of 1923-1924:

“Generously, you ask what I do. Aside from the activities exposed in last week’s disgusting note, I labor, and write innumerable theses, notes, poems and junk; I go to the math lib and read and to the Phil lib and divide my time between Meinherr Russell and the contemplation of a most beautiful and lovely lady who is writing a thesis on Spinoza – charmingly ironic, at that, don’t you think?; I make stenches in three different labs, listen to Allard [a professor of French] gossip about Racine, serve tea and talk learnedly to a few lost souls, go off for the weekend to distill the low grade energy into laughter and exhaustion, read Greek, commit faux pas, search my desk for letters, and wish I were dead. Viola.”

The remarkable thing about this letter is the quiet desperation disguised as frenzied erudition; you get the feeling that Robert kept moving in order not to sink into despondency. But despondency regarding what? Some of it would undoubtedly have been the intense desire to excel and take in as much knowledge as possible, but the letter also hints at disappointments concerning romantic attachments. As his friends remember, Robert never seems to have seriously dated while at Harvard; in that respect he seemed to be the 1920s equivalent of a quintessential, socially awkward nerd. Apart from Fergusson and Horgan and a few others, he seems to have made few friends at Harvard, generally choosing to keep to himself and shut himself up in the library or his own room studying. To get through the day without interruption, he whipped up a high-energy breakfast concoction called “black and tan” – toast slathered with a layer of peanut butter which was slathered in turn with a layer of chocolate syrup.

While he did not wear his erudition and diverse interests lightly, Oppenheimer was careful to sustain the impression in the minds of others that it all came easily to him, and most of it did. At the beginning of his time at Harvard, he occupied 60 Mount Auburn Street in Cambridge with a roommate named Fred Bernheim who late became a well-known professor of pharmacology at Duke University. Bernheim regarded Oppenheimer as being just a little too overweening in the way he regularly quoted Verlaine or Baudelaire but he also found Robert’s broad interests and knowledge intriguing. As he remembers:

“He wasn’t a comfortable person to be around, in a way, because he always gave you the impression that he was thinking very deeply about things. When we roomed together he would spend evenings locked in his room, trying to do something with Planck’s constant or something like that. I had visions of him suddenly bursting forth as a great physicist, and here I was just trying to get through Harvard.”

Later Bernheim credited Robert with steering him toward a career in medicine by developing in him an appreciation for the scientific method.

Oppenheimer’s personality at Harvard already displayed some of the important qualities that were to both attract and repel people later in his life. While most people, like Bernheim, were dazzled by his quick mind and erudition across a remarkable variety of subjects, some were put off by what they saw as showing off, pomposity and baroque exaggeration. These traits were responsible for both his triumph and his doom.

In one of the letters to Smith, Robert casually refers to the six-course load that would enable him to graduate in just three years. Along with “Heat and Elementary Thermodynamics”, “Differential and Integral Calculus” and “Experimental Organic Chemistry”, they include “Theory of Knowledge”, “General View of French Literature” and a course on probability. Remarkably, he plowed through the famous 3-volume set on the foundations of mathematics, the “Principia Mathematica” of Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead, in a course taught by Whitehead himself when he was a visiting professor. Only one other student whose name has been lost to history braved the course.

While he had entered Harvard intending to major in chemistry Oppenheimer’s interest started to turn toward physics through these courses. In a 1963 interview he said,

“I can’t recall how it came over me that what I liked in chemistry was very close to physics; it’s obvious that if you were reading physical chemistry and you began to run into thermodynamical and statistical mechanical ideas you’d want to find out about them…it’s a very odd picture; I never had an elementary course in physics, and to this day I get panicky when I think about a smoke ring or elastic vibrations.”

Thermodynamics seems to have been a topic of enduring interest, in particular: another friend named Jeffries Wyman who became a distinguished biochemist remembered Robert walking into his room one hot spring day and saying, “What intolerable heat. I have been spending all afternoon lying on my bed reading [James] Jeans’s “Dynamical Theory of Gases”. What else can one do in weather like this?”. By the time he progressed into his final year, while he would still major in chemistry, it was clear that Robert’s interests lay in physics. In one of his letters he petitioned the physics department to let him skip an elementary physics course and take an advanced physics class, citing as evidence a long list of physics textbooks that he said he had read. When the committee in charge of the decision allowed him to take the course, one of them is purported to have said, “Well, if he says he has read all these books he is obviously a liar; but he should get a PhD for knowing their titles.” One striking aspect of Oppenheimer’s education at Harvard is the scattered, incomplete nature of his learnings in mathematics and physics. Given his later accomplishments in theoretical physics this background appears even more remarkable and attests to how quickly he could self-learn and fill in the gaps in his formal education,

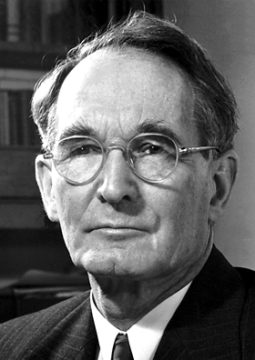

Two important influences set Oppenheimer up for his physics career. While Harvard at the time had no figures of the caliber of Ernest Rutherford or Niels Bohr in Europe, two of the courses Oppenheimer took were taught by the physicists Edwin Kemble and Percy Bridgman. Kemble was essentially Harvard’s resident theoretician, Bridgman its resident experimentalist. Bridgman in particular who was good enough to win a Nobel Prize later for his work on high-pressure physics and who also wrote articles and books on the philosophy of science had a lasting influence on Robert’s education and outlook. “I found Bridgman a wonderful teacher,”, Oppenheimer later remembered, “because he never really was quite reconciled to things being the way they were…he was a man to whom one wanted to be an apprentice.” Bridgman became, in effect, Robert’s undergraduate thesis advisor, advising him on research and coursework and writing recommendation letters for him when Robert was applying for graduate study. Even with his professor Robert could not help showing off and nitpicking. When he was once invited to Bridgman’s house for dinner, Bridgman showed him a photo of a Greek temple built in Segesta around 400 B.C. Robert disagreed, saying, “I judge from the capitals on the column that it was built about fifty years earlier.”

As he approached his graduation, it was clear to Oppenheimer, as it would have been to any aspiring physicist then, that Europe was where all the excitement in the world of physics was. While Rutherford had been revolutionizing experimental physics with his discoveries of the atomic nucleus and atomic transformations, Bohr and Einstein had been revolutionizing theoretical physics with their theories of relativity and atomic structure. While the United States had no comparable tradition in theory, the country was halfway decent when it came to experiment, with Albert Michelson, Arthur Compton and Robert Millikan doing Nobel-caliber research. Yet it was clear that Rutherford’s lab in Cambridge was the place to be if one wanted to do experimental physics. At this point, with his background working with Bridgman, Oppenheimer goal was to do experimental work.

So he had Bridgman write a letter of recommendation to Rutherford. The honesty in Bridgman’s letter is revealing. After commenting on Oppenheimer’s “perfectly prodigious power of assimilation”, he noted that “his weakness is on the experimental side. His type of mind is analytical rather than physical, and he is not at home in the manipulations of the laboratory…It appears to me that it is a bit of a gamble as to whether Oppenheimer will ever make any real contributions of an important character, but if he does make good at all, I believe he will be a very unusual success.” Then, perhaps more revealingly but emblematic of the time, Bridgman wrote, “As appears from his name, Oppenheimer is a Jew, but entirely without the usual qualifications of his race.”

Since Oppenheimer’s ineptitude for experiment would be responsible for a major emotional disaster that befell him later, it’s worth asking why Bridgman and Robert approached Rutherford when Robert’s lack of experimental ability was already so apparent. Part of it was probably Robert’s overconfidence, a trait that came from his prodigious academic performance over the previous three years. Part of it was Rutherford’s fame that probably made it too tempting to not apply to his laboratory. But part undoubtedly must have been the fact that while Robert was exposed to the workings of experimental physics by working in Bridgman’s laboratory, there was no comparable education he had had in theory, both because there was no world-class theorist at Harvard and because Oppenheimer’s slapdash, incomplete education in mathematics and physics would have given him no taste for the pleasures of theoretical contemplation.

In any case, the stage set was set for Robert’s entry into the world of European physics, an intellectual crucible in which revolution after revolution was being forged. In 1925 he graduated summa cum laude with his degree in chemistry. Instead of attending the graduation ceremonies, he and some of his friends repaired to a roommate’s room for a small celebration. While his roommates were intent on getting drunk, Robert had one drink and retired. He was ready to take on the world of physics. It was an effort that was to take him almost to the verge of insanity.

Principal references:

- Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and Recollections – Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner, 1980

- American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer – Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, 2005