by Herbert Harris

Is mathematics created or discovered? For over two thousand years, that question has puzzled philosophers and mathematicians alike. In Plato’s Meno, Socrates encourages an uneducated boy to “discover” a geometrical truth simply by answering a series of guided questions. To Plato, this demonstrated that mathematical knowledge is innate, that the soul recalls truths it has always known. The intuitionists of the early twentieth century, however, rejected this idea of eternal forms. For thinkers like Poincaré and Brouwer, mathematics was not revelation but construction: an activity of the human mind unfolding in time.

The debate continues today in an unexpected new arena. As artificial intelligences start to generate proofs, conjectures, and even entire branches of formal reasoning, we are prompted to ask again: what does it mean to do mathematics? Current systems excel at symbol manipulation and pattern matching, but are they truly thinking in any meaningful way, or just rearranging signs? The deeper question is how humans do mathematics. What happens in the brain when a mathematician recognizes a pattern, intuitively sees a relation, or invents a new kind of number?

In what follows, I’ll trace that question from ancient philosophy to modern neuroscience and then to the newest foundations of mathematics. We’ll see that mathematical invention may be the natural expression of the brain’s recursive, embodied intelligence, and that this perspective could transform how we think about both mathematics and AI. Read more »

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

There’s an old story, popularized by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806-1871) in A Budget of Paradoxes, about a visit of Denis Diderot to the court of Catherine the Great. In the story, the Empress’s circle had heard enough of Diderot’s atheism, and came up with a plan to shut him up. De Morgan

Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down.

Two weeks ago, outside a coffee shop near Los Angeles, I discovered a beautiful creature, a moth. It was lying still on the pavement and I was afraid someone might trample on it, so I gently picked it up and carried it to a clump of garden plants on the side. Before that I showed it to my 2-year-old daughter who let it walk slowly over her arm. The moth was brown and huge, almost about the size of my hand. It had the feathery antennae typical of a moth and two black eyes on the ends of its wings. It moved slowly and gradually disappeared into the protective shadow of the plants when I put it down.

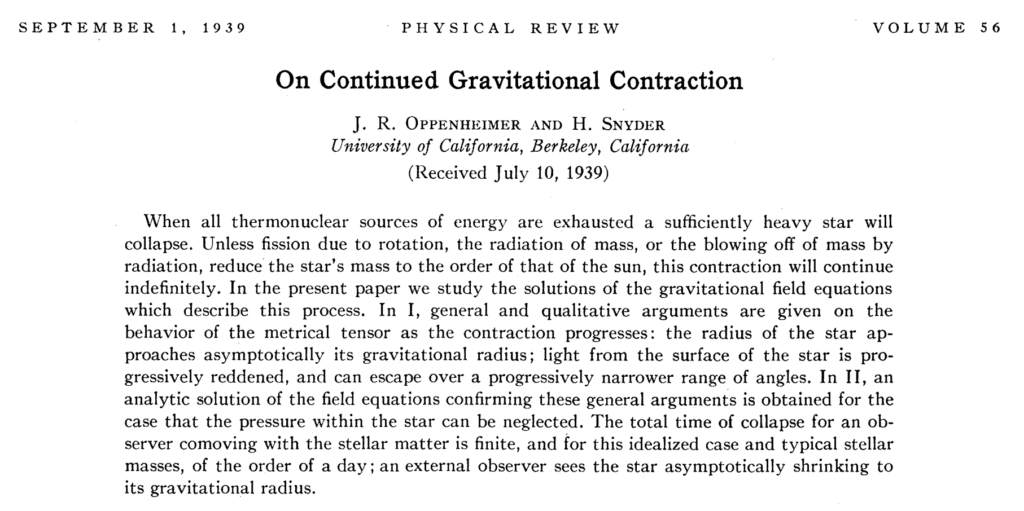

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.

There is a sense in certain quarters that both experimental and theoretical fundamental physics are at an impasse. Other branches of physics like condensed matter physics and fluid dynamics are thriving, but since the composition and existence of the fundamental basis of matter, the origins of the universe and the unity of quantum mechanics with general relativity have long since been held to be foundational matters in physics, this lack of progress rightly bothers its practitioners.