by Joseph Shieber

Suppose that you’re sitting at a pristine, white desk and are presented with the following scene (graciously rendered by Google Bard from a description by me):

How would you describe what you see? Maybe something like, On the desk in front of me there’s a medium-sized, shiny green sphere in front of a large, matte red cube.

The process by which you see, however, doesn’t involve the wholesale transmission of information about discrete objects from the environment to your consciousness. Rather, that process involves the decomposition of information into constituent components. Very roughly, the rods and cones in your eyes encode light reflectances from surfaces in your immediate environment into biochemical signals and communicate them, by way of your optic nerve, to your visual cortex, where those signals undergo further processing. Some parts of this process involve distinguishing between light and dark, other parts involve the detection of edges, lines, and orientations, while still other parts involve encoding for color, motion, depth, and object-hood.

The way that this process occurs seems to present a problem. How is it that the discrete pieces of information — shiny, matte, red, green, sphere, cube, in front, behind, etc. — get put back together in the right way when that information eventually makes its way to your consciousness? Given the scene on your desk and the process by which your sense organs and brain process that visual information of the scene, why do you become aware of the right collection of properties – the green, shininess, and spherical shape belonging to the object in front, and the red, matte surface, and cubic shape belonging to the object behind? In fact, why are the properties even connected at all in your consciousness, rather than appearing as separate impressions of color, shape, surface, etc.?

This puzzle of how it is that the visual properties that we sense are “bound” together into experiences of objects is one version of the “binding problem” in neuroscience. Merely one version, because we can easily imagine others. To take just one further example, when you then reach out your hand to grasp the object in front on your desk, why do you register your tactile experiences as belonging to the same green, spherical object that you see?

Though the binding problem is still a live problem in 21st century neuroscience, it was actually anticipated more than 2000 years ago, in the Nyāya Sutras (Sutras 3.3.1-14). There, the author of the Sutras uses what is basically the binding problem to argue against the idea that the self might consist in nothing more than a collection of all of the component parts of the living human body. This latter, materialist, view was defended by the Cārvāka school, one of the rival schools of the Nyāya. Read more »

In

In  Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2011- …

Amar Kanwar. The Sovereign Forest, 2011- …

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

The last time I see Sam she’s sitting at the vanity in her bedroom, carefully examining her 16 year-old face in its lighted mirror.

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

Did we need to have a Civil War? Couldn’t the two sides, geographically defined as they were, simply part before the shooting started? Did Lincoln intentionally choose war for any one of a variety of unworthy reasons that stopped short of necessity, including even something so mundane as a fear of losing face? Or was he faced with an intractable situation for which there was no simple, satisfactory answer—a type of political Trolley Problem?

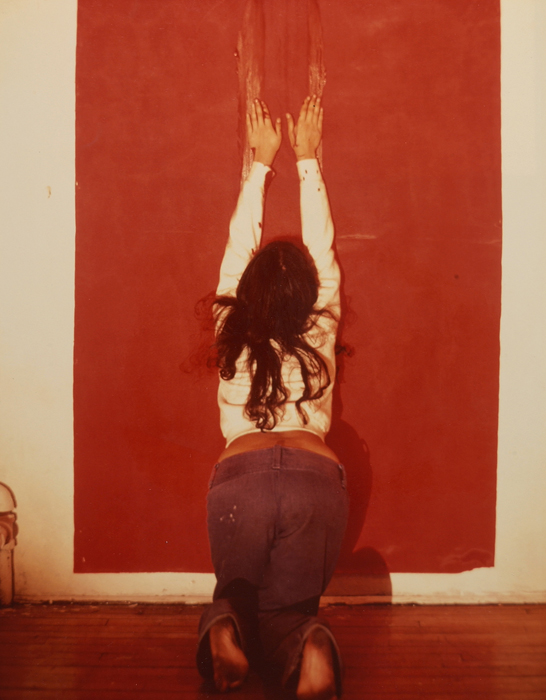

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.

Ana Mendieta. Body Tracks, 1974.

I recently binge-watched all of

I recently binge-watched all of