by Eric Bies

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

On the night of July 13, 1977, the old god Zeus roused from his slumber with a scratchy throat. Reaching drowsily for the glass by his bedside, his arm knocked a handful of thunderbolts from the nightstand. Swift and white, they rattled across the floor to the mountain’s, his home’s, precipitous edge: off they rolled and dropped to plummet through the dark. That night, great projectiles of angular light splashed against and extinguished New York City’s billion fluorescent eyes.

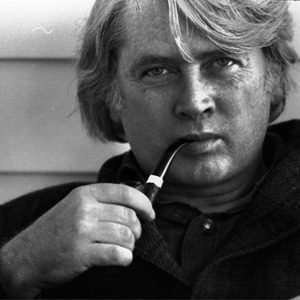

A week later, John Gardner turned 44—a fortuitous number, for the American novelist and medievalist was on a roll. That year alone he was set to see the publication of two children’s books, a collection of short stories, a work of criticism, and a biography. Six years had passed since the release of a short novel, Grendel, his ingenious Frankenstein-ing of the Beowulf myth that is read in American high schools to this day. Eleven years later, at the age of 49, Fate would see fit to fling him from his motorcycle and strike him dead. But first, in 1977, he had to publish his Life and Times of Chaucer. Owing to novelistic tendencies, the work has probably received more admiration from laymen than academics (rather redemptive as far as literary legacies go, actually). It is one of those books, unhampered by its erudition, that is a joy to read all the way through to the bitter end, and its final paragraph, as Steve Donoghue has pointed out, remains one of the strangest, strongest, and most memorable deathbed scenes in our literature:

When he finished he handed the quill to Lewis. He could see the boy’s features clearly now, could see everything clearly, his “whole soul in his eyes”—another line out of some old poem, he thought sadly, and then, ironically, more sadly yet, “Farewell my bok and my devocioun!” Then in panic he realized, but only for an instant, that he was dead, falling violently toward Christ.

The “bok” to which Chaucer says his goodbye is, of course, The Canterbury Tales. Had he had the time, Chaucer would have gladly doubled the length of his book. Who knows what he must have truly felt to take leave of his Knight, his Miller, his Pardoner, his Monk? Readers of this magnificent story cycle will readily sympathize. For even a writer as self-assured as Chaucer could not have anticipated how well and how dearly his countrymen would come to know his characters. The fact that the book remained unfinished at the time of his death did practically nothing to impede its momentous rise. Thankfully, just sixteen years after Chaucer fell violently toward Christ, England got its Gutenberg. When William Caxton set up press in Westminster, the first pages he printed were wet with the ink of Chaucer’s quill.

We know that minus Chaucer we would be minus at least one Shakespeare play. But the Chaucer that persists in popular admiration is not the author of Troilus and Criseyde. The Chaucer we continue to enjoy is—like Kafka—a sensibility so deeply intrinsic to our culture that we struggle to imagine what life must have been like before it had taken root. Notice how, of all the authors Shakespeare is said, by some, to have not been able to read—second only to Ovid—stands Chaucer. But there’s the rub; all it takes is a restful reading of the Summoner’s Tale to find fault pretty immediately with the rarefied (not to say paranoid) vision of Oxfordians everywhere: one would hardly have needed a courtly education to have found farts funny.

Look. Some books are windows—they give onto vistas of human experience diverging from our own. Other books operate as mirrors, reflecting back something singular about ourselves. We might say that Chaucer’s earthy genius—both window and mirror—resides precisely in this remarkable capacity for showing us who we are through the people who surround us. (Who hasn’t known a Wife of Bath?) During his inaugural lecture as an Oxford Prof., John Ruskin made the point with more elegance and sensitivity to the pith of it than anyone else has managed.

I think the most perfect type of a true English mind in its best possible temper, is that of Chaucer; and you will find that, while it is for the most part full of thoughts of beauty, pure and wild like that of an April morning, there are, even in the midst of this, sometimes momentarily jesting passages which stoop to play with evil—while the power of listening to and enjoying the jesting of entirely gross persons, whatever the feeling may be which permits it, afterwards degenerates into forms of humour which render some of quite the greatest, wisest, and most moral of English writers now almost useless for our youth. And yet you will find that whenever Englishmen are wholly without this instinct, their genius is comparatively weak and restricted.

What is it about the English that lends authority to the charm and tickle of all that is artfully foul, fatuous, scurrilous, and broadly indecent? Chaucer is funnier than Shakespeare, Dickens (who is buried, like Chaucer, at Westminster Abbey) beats out Sterne (who is not), and Wodehouse (tucked under Long Island sod) might just be in a class of his own—but they are all funny and they are all English, and their funniness, somehow and ineffably, is instrumental to the snugness of their station in our cramped and beleaguered canon.

Gardner himself took strides toward reconfiguring the criteria. It wasn’t humor, however, that he was after. In a discussion with William Gass in 1978, he staunchly defended a position that was already inviting derision, making enemies, and heaping controversy in the world of books:

If we look back through the history of literature, [writers who failed to seriously engage questions of morality in their writing] have not been the ones who have been loved and who have survived. Again and again we’re moved by Achilles, we’re moved by the best of Shakespeare, Chaucer and others we keep going back to. Writers who give us visions to which we say, with all our unconscious minds as well as our conscious minds, “That’s just not so,” we don’t read.

Here was the essence of yet another Gardner publication, out that year, On Moral Fiction. The best writing, Gardner argued, does not make a chessboard of literature; it grapples instead with questions of right and wrong and of life and death. In this sense the book’s title might have been a tad misleading; it was as much concerned with the moral as it was with the immoral; it pushed and did not pull; it was a Molotov cocktail lobbed through the window of literary postmodernism.

The debate raged on for a little while, but only four years later Gardner was dead. Gass, nearly a decade Gardner’s senior, would go on living and writing, writing and living, until 2017. In later years, he remembered Gardner fondly and missed him deeply. He also penned many books Gardner would have deemed immoral, inspiring a whole new generation in kind. Sometimes these books could even turn a nice profit—as witness the sale of 2015’s City on Fire, a 927-page mega-novel about the blackout in 1977. Alfred A. Knopf, Gass’s longtime publisher, made headlines after announcing author Garth Risk Hallberg’s astounding $2 million advance.

When Zeus had taken his sip of water and turned over in bed, just as he was drifting off, a thought came to him. He sat up and steadied himself against the headboard. Can a god experience what man calls coincidence? Just then, Hermes returned and made himself known with a tap at the door. Argus had been taken care of.