by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

I was nineteen when I first saw Venice. My college boyfriend and I had taken an overnight train from Vienna and arrived in the mist of early morning. It was late summer. This was at the tail end of almost three months in India, where I saw my fill of glorious wonders. Still, nothing could have prepared me for my first glimpse of the fabled city. First of all, I hadn’t expected the Grand Canal to be right outside the train station. Boarding a vaporetto, I sat speechless. The canal was shimmering like a vision from a dream. Church bells could be heard just above the loud din of the boats, and everywhere I looked: marble palaces stood crumbling into the water. I vividly remember my heart racing as I looked around, not believing the place was real.

“A wonder of the world,” my boyfriend called it on the train from Vienna.

And when I at last found my voice, I asked, “Why does anyone live anywhere else?”

He just laughed.

That was in 1990.

Then as now, traveling to Venice meant being able to view the work of the dazzling trio of Venetian artists that Henry James claimed would “form part of your life in Venice.” Giovanni Bellini and Tintoretto, as well as the great Carpaccio, said James “shall illuminate your view of the universe.” James was hinting at the way that these painters’ works exert an overwhelming power, not only over the way we see Venice, but over our vision of the world. And this is especially true when the great pictures are viewed in situ, in the palaces and churches for which they were originally created.

Connoisseurs have become accustomed to viewing art through the lens of Kant, where art is understood as being a realm of its own, differentiated from other activities of life. Autonomous and self-sufficient, their purpose is simply to be rather than to instruct, to edify, or be of use. Art, insisted Kant, must be appreciated in disinterested contemplation of the object — for its own sake.

Modern museums are a by-product of this understanding, whereby works of art are for the most part, deprived of cultural or practical context. I am not the first person to make this point, but I think it bears repeating, that when we banish beauty to museum glass cases, we are in an effect banishing beauty itself from our daily lives. And in this way, our lives become enslaved to a kind of efficiency whereby only the rich can have “use plus beauty” and the rest of us must be content to go and see beauty at the public museums on our days off.

This was, after all, the basic concept behind the founding of the Metropolitan Museum in Manhattan. For all people to have a place of beauty in their lives, no matter how challenging their circumstances.

2.

2.

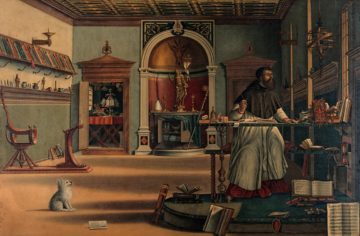

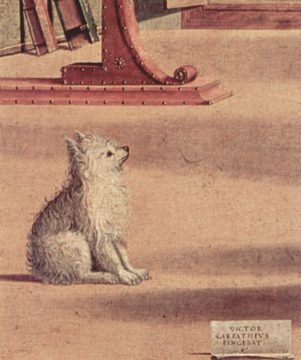

Being the painter perhaps most closely associated with Venice, it remains rare to find Carpaccio’s pictures in shows outside the lagoon. And like a lot of people, I was surprised to learn about the unprecedented exhibition Vittore Carpaccio: Master Storyteller of Renaissance Venice at the National Gallery in Washington DC (November 20, 2022 – February 12, 2023). The entire show is traveling back to Venice where it will open next at the Palazzo Ducale. Some of the artist’s most famous works are included, such as “Saint George and the Dragon” and “Saint Augustine in His Study,” the latter with its famous white pup that John Ruskin thought was the spitting image of his own ‘white Spitz Wisie’ (Whatever that is…!)

Another famous work, which even tourists not interested in art will surely see on a visit to the city is the iconic “Lion of Saint Mark” (1516) in the Palazzo Ducale. With one foot on land and one in the waters of the lagoon, the winged lion holds open a book with the words: “Peace to you, Mark my Evangelist.” This refers to the prophesy that the Evangelist Mark would find his final resting place in Venice—something which became true when Venetian merchants removed his remains from Alexandria in the 9th century, hiding them in a barrel of pork, which was the one place they were sure the Muslim merchants would not want to examine. Bringing them back to Venice, Mark’s remains would eventually find a home in a great basilica especially built to house them.

The painting of the winged lion, the fairytale vision of the campanile, domed basilica and Doge’s Palace, with a flag on a high mast and galleons anchored in the basin looms behind the winged lion, has become the long-time symbol of the city. It’s surprising that the painting was ever allowed to leave the city.

Travel writer Jan Morris, like Henry James and John Ruskin before her, was infatuated with Carpaccio. In her charming book Ciao Carpaccio! she wrote lovingly about his gentle pictures, painted in brilliant Venetian colors. Veritable bestiaries of enchanted animals, she counted winged lions and dragons among the peacocks and rabbits. In his pictures, Morris also delighted in unicorns, a basilisk, cherubs, and a multitude of angels. A great painter of dogs, Carpaccio was an even better painter of birds.

I am sure that I am not the first person to go birdwatching in his oil paintings. From his doves, peacocks, grebes, and cormorants, he is most famous for his colorful red parrots.

According to Jan Morris, John Ruskin was also taken by Carpaccio’s menagerie. At the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, there is a small watercolor drawing that is a copy of Carpaccio’s red parrot painted by Ruskin. Calling it a scarlet parrot, Ruskin wondered if it wasn’t an unknown species, and so decided to paint a picture of it to “immortalize Carpaccio’s name and mine.” It might be classified as Epops carpaccii, he suggested—Carpaccio’s Hoopoe.”

3.

The longer a person gazes upon a Carpaccio painting, the greater the chances are that they will fall in love with his vision.

In Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station, a young American named Adam Gordon lands a prestigious fellowship in Madrid. Supposedly, he is working on composing “a long and research-driven poem, whatever that might mean” about the Spanish civil war. Actually, he has talked his way into the fellowship and is now halfheartedly trying to learn Spanish by reading the Quixote.

He is a self-described poseur, who —unlike that other famous fake Anna Delvey— is the product of an expensive education and great privilege back home in Kansas.

Antagonistic toward other wanna-be intellectual American expats in Madrid, he makes fun of the way they teach English to the children of the wealthy and how they speak Spanish with an affected peninsular lisp. And yet, he is himself doing what was at one time, at least, a most American thing to do: running off to Europe where he spends his days engaged in obsessive and self-involved navel-gazing.

“I wondered … if my experience of my experience issued from a damaged life of pornography and privilege.”

His “experience of his experience” is the pulsing anxiety of the novel. The book opens in the Prado Museum, where Adam goes each morning to stand in front of a certain painting. Perhaps this is an homage to Thomas Bernhard’s Old Masters, but instead of a Tintoretto, the narrator Adam spends his mornings in front of Van der Weyden’s Descent. One morning, however, an interloper is standing in front of the picture.

His picture.

Growing irritated, Adam watches as this stranger breaks down in tears.

“Could the man be having a profound experience of art?” the protagonist wonders. And more importantly, “Was he capable of such a profound experience of art?”

I have thought about how my own understanding of the world would be changed if I was to stand in front of a certain painting, day-in and day-out for weeks or months. Or years.

A new memoir has come out called, All the Beauty in the World, by Patrick Bringley, about a man who is grief-stricken after the loss of his older brother to cancer at twenty-seven.

Toward the end, sitting at his brother’s bedside in the hospital with his mother, they are utterly devastated into silence. A shaft of life streams in through a curtain and his mother says something like, “Look at us, we have become a fucking old masters painting.”

Like a pieta.

Unable to go back to life as usual, he quits his “promising job” at the New Yorker and becomes a guard at the Metropolitan Museum.

In the museum, every day he stares at beautiful works of art and slowly, slowly, he finds himself coming back to life. He heals, as his mind is re-ordered by the beautiful works of art he stands before every day for eight and twelve-hour shifts.

A year turns into ten.

4.

One of my favorite writers—and a friend of these pages, Morgan Meis has developed a new style of writing about art, one that is informed by a passionate looking. One could argue that this is not new, that Meis is returning to a time when intellectuals had charmingly erudite conversations about paintings, history, and music. Not only could they bedazzle at a cocktail party, but they could write about it too ‑ art inspired by art. His writing is reminiscent of William Golden’s classic discourse on Thermopylae or John Pope Hennessy’s study of the “Best Picture in the World.” Like these thinkers, Meis is able through the examination of the particular (work of art), to ponder deep truths.

In addition to his two books on specific works of art, I really admired an essay he wrote for Image Magazine, called From the Faraway Nearby, on Georgia O’Keefe.

I was never much of a fan of O’Keefe’s until I read this essay and immediately hopped in the car and traveled to Abiquu so I could see what Meis saw.

His basic premise is that O’Keefe’s art was experimental in the way she allowed her over-focus on an object to inform her paintings. What might seem surreal is in fact hyper-real, but we need to really look at the thing first.

“Go on, try and look at a flower for ten minutes. Twenty minutes. How about an hour.”

In Japanese, to see and to look is “miru.” But if you are writing, you can mix it up and choose between kanji that means to look 見るor kanji that means to view and appreciate 観る. Both are pronounced “miru.”

One of the most rigorous and challenging parts of the Japanese tea ceremony is the ritualized appreciation of the works of art used in the gathering of that day. This is kansho. 鑑賞

Students learn to slow down and really look at the utensils, the bowl, the hanging scroll, inhale and take note of the fragrances of the tea-room and the soundscape of the season outside.

“First, let’s notice the crackle and color of the glaze. It might evoke a landscape. Can you spot it?” My sensei would lead us in noticing certain aspects of the bowl. Her top students were adept at communicating their own reactions to objects as well.

In Bringley’s book about the Metropolitan Museum, he writes about his own deeply personal responses to art works. Just like a person laughs when something is funny, he says, we also react physically to beauty.

The trick is to slow down enough to notice—not just notice beauty itself but also one’s response to it.

5.

Henry James once referred to his own love of Carpaccio as “a throb of affection.”

I feel the same.

Not much is known about the artist Carpaccio. But we do know that he was a native son of the city. He shared this with the Bellini brothers with whom he was a contemporary. In fact, he probably studied under or alongside one of the Bellini brothers or perhaps with Antonella da Messina. Carpaccio, however, was not of high birth, as he is now believed to be the son of a fur trader. His early works date from around the time that Columbus first arrived in the Americas. But Carpaccio had little interest in matters happening outside the lagoon; for to him, Venice was the center of the world.

And so it was. And so it remains.

For some five hundred years, his paintings have represented the marvel that is Venice—from its costumed pageantry and religious miracles to its marble palaces, saints, relics, and canals. Carpaccio, in the words of John Ruskin, depicted “a magical mirror” onto that world.

A master storyteller, Carpaccio created massive pictorial cycles to tell the spiritual and material history of the city. And his vision was endlessly charming.

Morris writes of the quintessential Carpaccian window on the world, explaining that “in scholarly circles the name of Carpaccio chiefly signifies a distinguished practitioner of a particular genre of narrative painting. The genre thrived in Venice in Carpaccio’s day. It perhaps had its origins in the mosaics of the Basilica San Marco, which told the Christian stories in a host of glittering designs, and it was fostered by the Venetian scuole, religious, charitable and professional guilds of great importance in the social structure of the city.”

6.

My own favorite picture is kept in the place for which it was created—in one of the city’s scuole.

Today, when introducing foreign tourists to Venice’s scuole, tour guides will sometimes compare the medieval confraternities to modern-day business associations that carry out philanthropic activities, like the rotary club. That is probably not far off the mark. Carpaccio’s great narrative cycles were created to adorn the walls of several of these scuole. The pictures were not merely to decorate but served to tell edifying stories relevant to the confraternity, like the “Legend of Saint Ursula,” “the Life of the Virgin,” and the “Life of Saint Stephen.” Perhaps most famous are two of the paintings commissioned by the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni on the life of the three patron saints of the scuola: St. Jerome, St. George, and St. Trifon. These are two large-scale oil and tempera on canvas works, “Saint George and the Dragon” and “Saint Augustine in His Study.”

The latter painting was cited by both Jan Morris and Henry James as being their favorite picture in the world.

Now, that is saying a lot—especially since Henry James saw a lot of paintings in his life. But what is interesting is that despite the lack of a lion, Henry James mistook Saint Augustine for Saint Jerome. And more, he thought it was a picture of Jerome in heaven; for wasn’t heaven surely a warm study filled with books and music and a little white dog just like the picture?

Both the “Saint Augustine” and “Saint George” pictures still adorn the high walls of the scoula in Venice where Carpaccio painted them. But it must be said, they are not easy to see in the dark space there. This was something complained about in 1882 when James visited the Schiavoni and said, “the pictures are out of sight and ill-lighted, the custodian is rapacious, the visitors are mutually intolerable.”

While I cannot speak to the custodians’ personalities, I will say that the place remains as dark as James suggested—which was my own rationale for traveling thousands of miles from California to see the exhibition last month at the National Gallery.

While the Bishop’s staff –and the lack of a lion—is a dead giveaway that this is not Jerome but Augustine, Jerome is still there in spirit, as the picture depicts the moment when Augustine knew in his heart that his friend Jerome had died. Jerome comes to Augustine in that shaft of light, when everything seems to freeze and he knows: Jerome is gone.

In DC, the painting covered an entire wall and was positioned low enough to really get a good look at it—up close. Standing in front of it for an hour, I tried to commit all the details to memory… and the colors and light. I wanted to breath the picture in. And while I finally got to really look at the picture, I couldn’t help but feel the Saint George and Saint Augustine had been stripped of a certain charisma or gravitas when seen outside the scuola. Like books that forever sit next to each other on a shelf, certain paintings seem to belong alongside each other, like Las Meninas and Emperor Charles V at Mühlberg or all those Tintorettos in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. So, even though I was thrilled to stand before the picture and finally actually really see it, something did seem stripped away.

Where was the sound of the tourists talking loudly outside amidst the seagulls and pigeons? And what of the caretaker sitting quietly on a chair in the back of the dark and dusty space? And how about the other pictures in the cycle?

And yet, I still felt that rush of standing in front of Carpaccio. The thrill that fades into an optimistic joy at being alive and being able to behold such beauty.

A consummate storyteller, Carpaccio’s paintings bubble over with vibrant details, delightful birds, animals and botanicals, and warm, rich colors. His work, in the words of Marie Kondo, spark joy—and he has delighted connoisseurs from John Ruskin and Henry James to Jan Morris, having come to represent the singularity of that miracle city on the lagoon. And yet, any time you mention his name, people’s minds inevitably turn to “charcuterie” and a certain thinly sliced and pounded raw beef. And so, in case you were wondering, it was at Harry’s Bar, also in Venice, where the chef Giuseppe Cipriani invented the dish. The color of the raw meat was thought to evoke the shimmering red of a Carpaccio painting—hence, the name. Cipriani also created the famous cocktail, the Bellini.

Long live Venice!

++

To read:

All The Beauty In The World – By Patrick Bringley

Morgan Meis: From the Faraway Nearby – Image Journal

My reviews of Meis’ art books A World of Tears in Dublin Review and On Horses, The Apocalypse, And Painting As Prophesy in 3QD

Ben Lerner’s novel, Leaving the Atocha Station

Bernhard’s novel Old Masters

My essay on Bernhard and Vienna