by Claire Chambers

Soon after the pandemic commenced its ‘global humbling’ in March 2020, I took on a humbling of my own in the form of learning Hindi. Trying to speak a new language makes most adults feel vulnerable. There is little to hold onto, so the unfamiliar language feels slippery, even treacherous. Compared to one’s easy intimacy with the mother tongue, second language acquisition entails surrendering to a shaky command of the foreign language for years, if not forever. They say languages learnt after a certain age will always be spoken with an accent. But oh well, embrace the accent! Experts put themselves in the uncomfortable position of becoming beginners again.

Soon after the pandemic commenced its ‘global humbling’ in March 2020, I took on a humbling of my own in the form of learning Hindi. Trying to speak a new language makes most adults feel vulnerable. There is little to hold onto, so the unfamiliar language feels slippery, even treacherous. Compared to one’s easy intimacy with the mother tongue, second language acquisition entails surrendering to a shaky command of the foreign language for years, if not forever. They say languages learnt after a certain age will always be spoken with an accent. But oh well, embrace the accent! Experts put themselves in the uncomfortable position of becoming beginners again.

Most adults learn languages for one of two reasons: to make a living, or ‘to slip into another community’. However, my own motivations doubled back on each other, embracing both of these rationales.

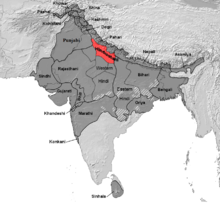

When it comes to making a living, I have been teaching and researching South Asian literature in English for twenty years. In doing so, I’ve lived in India and Pakistan for a total of sixteen months, and picked up some words from Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, and Pashto along the way. But I had no confidence and, to be frank, no grammar. So, when activities ground to a halt in the first lockdown, it seemed like a good time to embark on a linguistic journey. Physical travel to the subcontinent had become impossible. With even my fifty-mile daily commute knocked out I was faced, like everyone, with a yawning expanse of time to fill. Many people turned to language learning at this time. And I had the vague idea that learning a South Asian language would help my research. At the very least, it would be something to do.

As for slipping into another community, I must admit I often feel a bit trapped in my own country. Although there are many things (and of course people) in Britain that I love, I’ve always felt aslant from Britishness. Especially since Brexit, I have a sense that the nation doesn’t name me. Indeed, I am one of about half a million people who applied for, and in my case were given, Irish citizenship following the EU referendum of 2016.

Hindi, I thought, would help improve my domestic situation and mitigate the monolingual bias in my research. I was hoping to find a community abroad, and to infuse my daily life in northern England with a tincture of the subcontinent’s rich diversity. If it is possible to feel homesick for a foreign country, then I am homesick for two. I feel nostalgic for a South Asian life I didn’t lead. And I yearn to fly to those neighbours and rivals – Pakistan and India – whose landscapes and peoples often populate my dreams.

hoping to find a community abroad, and to infuse my daily life in northern England with a tincture of the subcontinent’s rich diversity. If it is possible to feel homesick for a foreign country, then I am homesick for two. I feel nostalgic for a South Asian life I didn’t lead. And I yearn to fly to those neighbours and rivals – Pakistan and India – whose landscapes and peoples often populate my dreams.

I had been good at languages as a child, studying German to AS level and French to both A- and S-level. But it’s completely different learning a language as an adult compared with at school. However much online community-building you try to do, as an adult you’re basically on your own with the language.

For another thing, Hindi is difficult for many Westerners, despite being English’s distant cousin in the Indo-European language family. It is highly gendered, like many European tongues but unlike English. In common with German, it is a Subject-Object-Verb or SOV language. Accordingly, I found myself struggling once more with (to SVO ears) the way the action seems delayed until the end of the sentence or at least the grammatical clause.

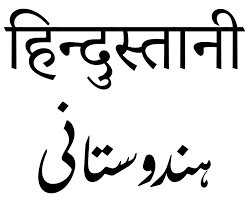

Most dauntingly, Hindi uses the beautiful but on first glance strange writing system of Devanagari. And not only had I become more or less monolingual since letting languages slide after leaving school, but I have always been monographic, as it were. Knowing only one alphabet, there was a big part of me that considered myself incapable of performing the intellectual feat of moving outside the Latin script. When Romeo is asked in Shakespeare’s play if he can read, he jokes, ‘Ay, if I know the letters and the language’. These were my only stumbling blocks too! But one Mexican language teacher told me empoweringly that since a human has created the script, a human can read it.

Most dauntingly, Hindi uses the beautiful but on first glance strange writing system of Devanagari. And not only had I become more or less monolingual since letting languages slide after leaving school, but I have always been monographic, as it were. Knowing only one alphabet, there was a big part of me that considered myself incapable of performing the intellectual feat of moving outside the Latin script. When Romeo is asked in Shakespeare’s play if he can read, he jokes, ‘Ay, if I know the letters and the language’. These were my only stumbling blocks too! But one Mexican language teacher told me empoweringly that since a human has created the script, a human can read it.

I also found I went through a ‘silent period’. This is a normal and productive but soul-destroying phase in adult language acquisition. Ordinarily eloquent people are struck dumb by their lack of vocabulary and slow adjustment to the grammar of the target language. Katherine Russell Rich, an author whose work I will discuss in more detail in my next blog post, expresses this experience vividly:

I was a companion with one active verb tense, a language ed student tearing forward on one gear. The talk would rev, then I’d screech through an intersection, then we’d all fall quiet again. I hated the silences, reminders of how powerless I was, though had I only known, silent was exactly how I needed to be then.

‘If you take a child, six or seven, and put them in France, the child will go through a silent period,’ says Martha Young-Scholten, a professor of second language acquisition studies at Newcastle University in England. ‘They won’t use the target language, then suddenly, after several months, they’ll open their mouths and start speaking fluently, and everyone’s amazed. Adults and teenagers often struggle against doing this. They think they have to try right away. But listening without speaking is important.’ Only months later did I find that the dread silences had allowed words to set.

As Rich intimates, although their progress may feel glacially slow during this period, learners are making progress nonetheless. With that said, she may be over-egging it. Recent research suggests that the silent period may be a myth. At the very least, fatalistic assumptions about the inevitability of muteness will be counter-productive. But for my part there certainly were months or maybe a year when I was uncharacteristically quiet and awkwardly self-conscious about my linguistic ineptitude.

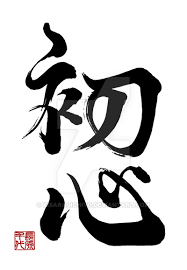

Amid all this self-doubt and confusion, the Japanese Zen Buddhist idea of Shoshin, or beginner’s mind, proved helpful to me. This idea suggests that the more expert and technically skilled a person is, the less creative they may become. Immersed in a field, their mind can get institutionalized, and interesting pathways are then closed off. Becoming a newly-hatched student again entails the asking of basic but meaningful first-principle questions in a way that can be illuminating. Even for specialists, if problems arise and they can’t see the wood for the trees, it may be worthwhile to step back and see the situation from a beginner’s mind.

Amid all this self-doubt and confusion, the Japanese Zen Buddhist idea of Shoshin, or beginner’s mind, proved helpful to me. This idea suggests that the more expert and technically skilled a person is, the less creative they may become. Immersed in a field, their mind can get institutionalized, and interesting pathways are then closed off. Becoming a newly-hatched student again entails the asking of basic but meaningful first-principle questions in a way that can be illuminating. Even for specialists, if problems arise and they can’t see the wood for the trees, it may be worthwhile to step back and see the situation from a beginner’s mind.

That’s one reason why I enjoy teaching so much. It enables a way of looking at an intellectual issue from a fresh perspective, with an openness to whatever may happen. And while I’m not sure my Hindi will ever be good enough to feed into my research, the language is already percolating into my teaching. If nothing else, the experience of the last few years has helped me develop greater insight into my students and the challenges they face.

Anyway, as far as Hindi was concerned, my mind was that of a true beginner! And so on 24 March 2020 I started Duolingo‘s course. I know the precise date because the app’s streak feature tells me I have practised for an unbroken 979 days since then. That’s the thing about Duolingo. Its Hindi course may be lamentably short, consisting of just two units, but it’s addictive as hell. In just four lessons at the start of Unit 1, it teaches the Devanagari script in an elegant and fun way. Sidenote: admittedly I had to keep repeating these four alphabet lessons for six months, as I’m a slow (if dogged) learner.

Anyway, as far as Hindi was concerned, my mind was that of a true beginner! And so on 24 March 2020 I started Duolingo‘s course. I know the precise date because the app’s streak feature tells me I have practised for an unbroken 979 days since then. That’s the thing about Duolingo. Its Hindi course may be lamentably short, consisting of just two units, but it’s addictive as hell. In just four lessons at the start of Unit 1, it teaches the Devanagari script in an elegant and fun way. Sidenote: admittedly I had to keep repeating these four alphabet lessons for six months, as I’m a slow (if dogged) learner.

Before too long, I had exhausted the course’s riches. In pursuit of new content, I flipped things around and started the longer अंग्रेज़ी course. Ostensibly I was studying English, but doing it through the medium of Hindi meant I picked up further vocabulary and turns of phrase. Finally, I spent time with just the first four script-based lessons of Arabic in Duolingo. I did this in order to try and master (mistress?) Hindi’s more Arabicized and Persianized sister language of Urdu – which language I will explore in a future blog post. These days I just practise old lessons on Duolingo, while having added to my repertoire some other apps like Mango, Ling, Clozemaster, and ReadAlong Google.

What’s more, Duolingo creates some semblance of the community of learners that schoolchildren have in abundance but adult learners woefully lack. Through Duolingo Events (which used to be free, but seem to have gotten uniformly expensive in recent times), I made some valued friends. I met that visionary Mexican polyglot I mentioned earlier. He teaches free classes in Hindi, Urdu, Arabic, and Mayan through the English medium on another social media platform called Discord. In addition, he knows Spanish, Persian, and Greek among other languages: it’s staggering! I also met diasporic Indians, not just from the UK and US but Trinidad, Suriname, and Mauritius. To list some final examples, I have met Buddhists based in India; south Indians keen to improve skills in their nation’s official language; the spouses of Indians scattered all around the world; and Bangladeshis who know Hindi through Bollywood.

Despite loving Duolingo’s gamification, it has to be said that no app, not even one offering group lessons, will truly teach you a language. After about six months, I therefore signed up with my first and most wonderful teacher, Babita Craig from Babita’s School of Hindi. Since my starry-eyed taster class, Babita and I have done Zoom lessons twice a week on average. It’s remarkable to realize that we still haven’t met in 3D, since by now she is my friend as well as my instructor. Hailing from Mussoorie in India’s northern Uttarakhand state, Babita has roughly a decade’s experience in language tuition from her work at Mussoorie’s famous Landour Language School.

Despite loving Duolingo’s gamification, it has to be said that no app, not even one offering group lessons, will truly teach you a language. After about six months, I therefore signed up with my first and most wonderful teacher, Babita Craig from Babita’s School of Hindi. Since my starry-eyed taster class, Babita and I have done Zoom lessons twice a week on average. It’s remarkable to realize that we still haven’t met in 3D, since by now she is my friend as well as my instructor. Hailing from Mussoorie in India’s northern Uttarakhand state, Babita has roughly a decade’s experience in language tuition from her work at Mussoorie’s famous Landour Language School.

As in the Super Mario Bros game, Babita opened for me a treasure box to reveal the linguistic power-up that is understanding postpositions. With my background in German I had been puzzling over Hindi’s grammar, fruitlessly trying to work out its case system. Babita has given me many other gifts, but explaining the way postpositions inflect the nouns that come before them was the key that unlocked the greatest bounty.

Babita’s teaching methods include (but are not limited to) rigorous grammar drills. I remember how slow I used to be and how much these drills would make me sweat. I’m still more hesitant in my speaking than I would like, and I make too many mistakes. Yet, nowadays I enjoy sampling Hindi’s seemingly limitless array of grammatical constructions. And the drills have been foundational for my understanding of how the grammar works and for habit formation.

Another resource I’m grateful for every day is Hindi University (not to be confused with a ‘real’ university of the same name in West Bengal). The organization was set up in 2011 by Ashutosh ‘Ashu ji’ Agrawal. Ashu ji is a resident of Washington DC and the author of the book Pingu Learns Hindi. At once passionate and patient, he offers an hour-long class each Sunday to a global community of learners via YouTube and Facebook Live. Out of this has developed an incredibly lively WhatsApp group, a real-world support network, and practice sessions generously arranged each week by active members of the group.

Another resource I’m grateful for every day is Hindi University (not to be confused with a ‘real’ university of the same name in West Bengal). The organization was set up in 2011 by Ashutosh ‘Ashu ji’ Agrawal. Ashu ji is a resident of Washington DC and the author of the book Pingu Learns Hindi. At once passionate and patient, he offers an hour-long class each Sunday to a global community of learners via YouTube and Facebook Live. Out of this has developed an incredibly lively WhatsApp group, a real-world support network, and practice sessions generously arranged each week by active members of the group.

As these resources helped advance my comprehension, an interesting discovery was how quickly my faltering attempts at Hindi pushed out from my brain any French or German I still retained from back in the day. I would be trying to think of the simplest French vocabulary – words like ‘his’, ‘her’, or ‘their’ – and all I could think of was ‘uska’ or उसकी/उसके, ‘apna’ or अपनी/अपने, and ‘unka’ or उनकी/उनके. In the end I had to google for the embarrassing reminder that the French pronouns are son, sa, ses and leur(s). My younger self would have laughed at this new me.

Then I did a bit of light research. Linguists think the mother tongue is fundamentally untouchable. Children learn languages like ducklings imprinting on whomever they encounter in their early days. Like the baby duck with its mum, no amount of immersion in a different linguistic context can displace the mother tongue from the mind. As for the previous second language of many adults trying to acquire a new tongue, though, this kind of memory blank regularly happens. ‘It’s like the new language shoves the other to the background,’ psycholinguist Ellen Bialystok told Katherine Russell Rich.

Then I did a bit of light research. Linguists think the mother tongue is fundamentally untouchable. Children learn languages like ducklings imprinting on whomever they encounter in their early days. Like the baby duck with its mum, no amount of immersion in a different linguistic context can displace the mother tongue from the mind. As for the previous second language of many adults trying to acquire a new tongue, though, this kind of memory blank regularly happens. ‘It’s like the new language shoves the other to the background,’ psycholinguist Ellen Bialystok told Katherine Russell Rich.

It’s possible to overstate the extent to which languages interfere with each other in this way. Perhaps the phenomenon mostly occurs at an early stage, while trying to acquire very basic words, like pronouns. At such times I think the brain has to prioritize in the way just described. Later on the languages learn to coexist with each other – and I certainly don’t mean to put people off from learning more than one language at a time!

Something similar apparently happens to bilingual people. Not that I’ll ever know first-hand what bilingualism feels like. But I supervise a final-year PhD student from Pakistan who is equally at home in English as with her home language of Urdu. During the chit-chat before one supervision, I was telling this student, Sauleha Kamal, about my lexical adventures. I expressed my frustration that Hindi only holds about seventy percent of its words in common with Urdu, the language I had originally wanted to study. In this regard, I mentioned राजनीती, and asked her for the equivalent Urdu word for politics since rajneeti seemed too Sanskrit-sounding. Despite her fluency and almost preternatural intelligence, Sauleha had a brain melt similar to my own French fail. It was only later that the Urdu word for politics, siyaasat or سیاست (from Persian) came back to her. She thought this was because she wasn’t accustomed to using South Asian languages with her English professor.

Later we talked on Twitter about this incident. She told me she had read that the bilingual brain practises something called language suppression to resolve language conflict. This means it subdues the non-target language depending on the context. Therefore, language selection is different when a bilingual person is speaking to someone who is fluent in the same languages, someone who is only fluent in one, and so on. Everything from visual cues to the interlocutor’s comfort level and knowledge goes into the bilingual brain’s unconscious calculation.

Salman Rushdie’s narrator from his third novel Shame famously states: ‘It is generally believed that something is always lost in translation; I cling to the notion … that something can also be gained’. The acquisition of a new tongue is a huge gain – one that is already immeasurable to me, fewer than three years into my endeavour. But this gain also involves losses: of old second languages, and perhaps too of the previously unquestioning intimacy with the mother tongue.

always lost in translation; I cling to the notion … that something can also be gained’. The acquisition of a new tongue is a huge gain – one that is already immeasurable to me, fewer than three years into my endeavour. But this gain also involves losses: of old second languages, and perhaps too of the previously unquestioning intimacy with the mother tongue.

What have I learned from all this? So much. And yet another humbling comes with knowing there is still so, so much Hindi to learn. I’m also conscious that my blog post is too long, and yet I’ve barely given a sense of the texture and character of this endlessly fascinating language. So next time I will move from beginner’s mind to the intermediate middle ground, zeroing in on the language’s uniqueness and how it is altering my worldview. Then for the final piece of what I envisage as a trilogy (though I have a bad habit of letting things get out of hand!), I plan to write about beginning all over again with Urdu. If you too can bear to start anew and don’t have better things to do now we’re told the pandemic is over, join me for the second and third staging posts on my three-part journey through Hindustani.