by Gus Mitchell

This article is from a presentation made for the Rosemary Bechler Inaugural Memorial Lecture, an event organised by DIEM25, of which Rosemary was a founder member. It took place at the Marylebone Theatre in London on January 21st 2024.

That music you just heard is a recording of the Aka People, recorded in the forests of the Central African Republic. The musicologist who collected it gave it the simple title: “Women Gathering Mushrooms.” I like that title because I think its literalness reveals something important. I don’t know if the Aka conceive of it as “art” in the same way that now, sitting in a theatre in London in 2024, we conceive of it. Undoubtedly though it is art in the truest sense.

Of course, it is very difficult––it is impossible––to avoid speaking in generalities when you’re using a word as general, as vast, as art. There are as many arts as there are artists. Avoiding abstraction is impossible. But that’s also part of what I’m going to try to say here. That is––that most of the ways we tend to think about art today are abstract. Too much so, I think. I think that art might in fact mean more than we currently allow it to. It might be more than we currently allow it to be. Read more »

I recently binge-watched all of

I recently binge-watched all of

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.

The Balkans isn’t everybody’s first choice for summer holiday, but that’s where we’re headed this year. First we’re flying to Chișinău, while we still can, and I don’t mean to be flip. Forgive my wavering confidence in Western guarantors of freedom, democracy and territorial integrity.

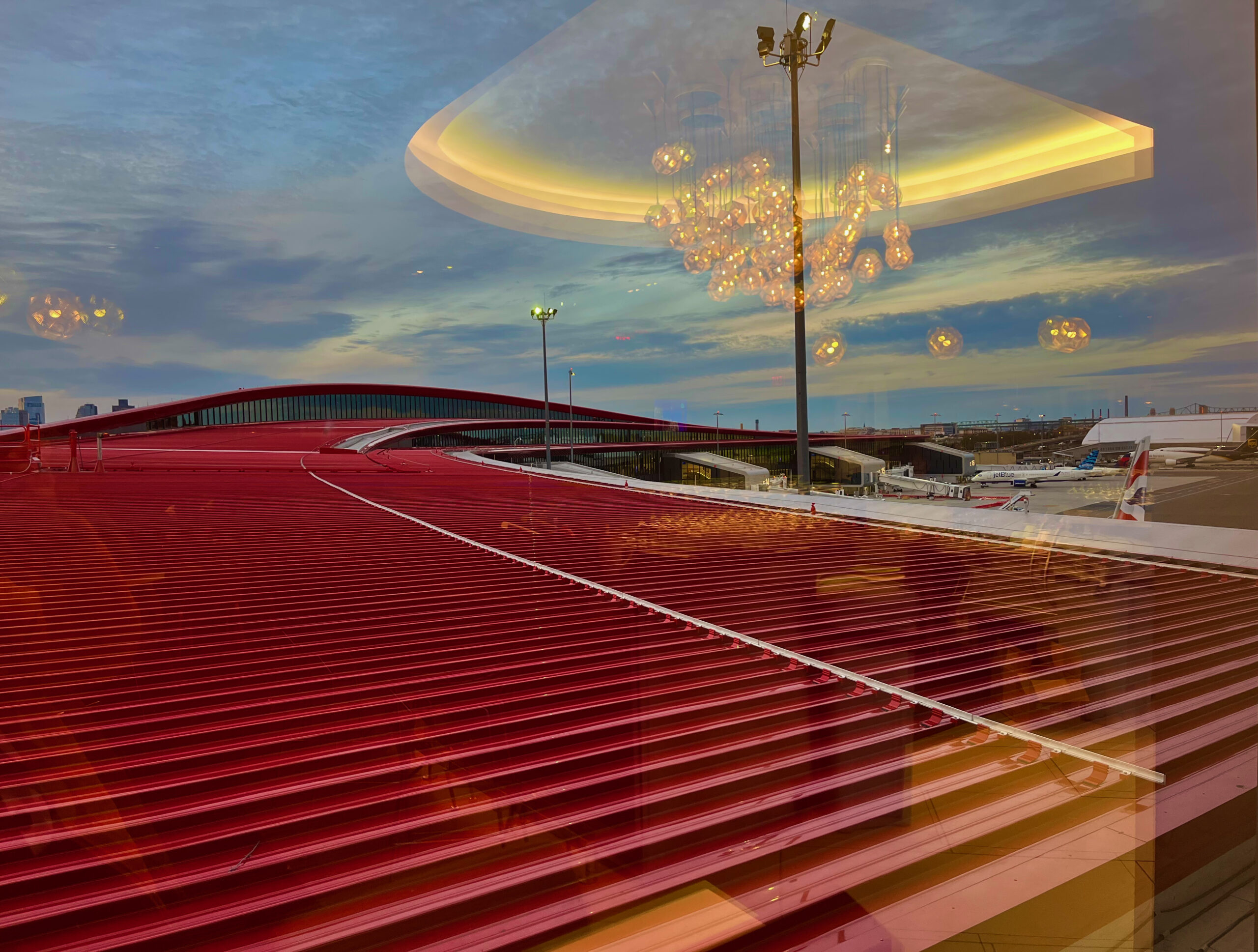

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

Sughra Raza. New Wing. November 2023

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III.

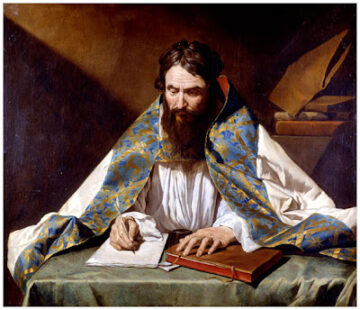

In September 2022, Fiona Hill claimed that with the war in Ukraine, World War III had begun. The statements of the American expert on Russia were clear: World War I and World War II should not be regarded as static and singular moments in history. Even though they were separated by a peaceful period, the latter is part of a whole process leading from one World War to the next. The peaceful period following the Cold War would then be comparable to the interwar period in the 1920’s and the 1930’s. From Hill’s processual point of view peaceful periods are as much part of major conflicts as the actual war periods themselves: from the Cold War via a peaceful period to WW III. As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

As an émigré from the dusty, sun-scorched Carthaginian provinces, there are innumerable sites and experiences in Milan that could have impressed themselves upon the young Augustine – the regal marble columned facade of the Colone di San Lorenzo or the handsome red-brick of the Basilica of San Simpliciano – yet in Confessions, the fourth-century theologian makes much of an unlikely moment in which he witnesses his mentor Ambrose reading silently, without moving his lips. Author of Confessions and City of God, father of the doctrines of predestination and original sin, and arguably the second most important figure in Latin Christianity after Christ himself, Augustine nonetheless was flummoxed by what was apparently an impressive act. “When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out for meaning, but his voice and his tongue were at rest,” remembered Augustine. “I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise.”

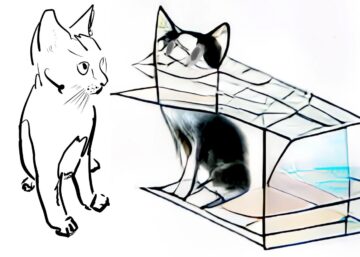

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.

Ten months ago Artificial Intelligence helped lift me out of a stubborn pandemic depression. Specifically, an AI image generator’s results from the prompt Schrodinger’s Cat; the name of the physicist’s thought experiment in which, under quantum conditions, a cat in a box could theoretically be both dead and alive at the same time—that is until the box is opened and an observation is made.